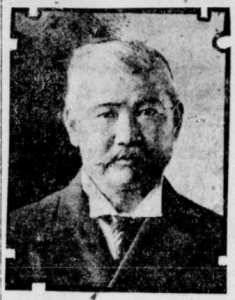

Moy Ni Ding: “The Grand Old Man of Chinatown”

Written by Colby Payne

Figure 1: Moy Ni Ding in his later years (Boston Globe, June 6 1931, Page 5)

Moy Ni Ding was born in Taishan, Guangdong Province, China, between 1855 and 1859 [1]. Little is known about his early life; according to his funeral announcement in the Boston Globe, he arrived in Philadelphia in 1876, and continued on to Boston within a few years [2]. As a member of the Moy family, one of the most prominent Chinese families in Boston [3][45], Moy Ni Ding and his children appeared frequently in local newspaper coverage, beginning in 1895 [4]; over time, this reportage evolved significantly. Early stories focused on Moy Ni Ding’s alleged criminal activities: in 1895 and 1896, he was twice fined for his alleged participation in running illegal lotteries in the city of Boston [4][5][6]. As his family grew, however, coverage evolved, and by the early 1900s Moy Ni Ding and his family were written about as leaders in the Chinese community of Boston [7][8]. Unfortunately, there don’t appear to be online archives for Chinese papers based in Boston in the 1890s, making it challenging to gain information about how Moy Ni Ding was perceived by members of his own community.

According to the 1900 US census, Moy Ni Ding married his first wife—possibly named Fung Shee or Fong She—in 1888 [9]. The couple appears to have had at least four children: Mamie or Ah So Non, born in Feb. 1893**[10][11]; William or Willie, perhaps born as Lan Doo or Lan Gee, born in July 1896 [12][15][16]; Rose, born in November 1898 [17]; and Lan Tue Moy, occasionally referred to as Moy Lung, born in March 1903 [13][14][18]. At an undetermined date after 1903 and several years before 1918, Mrs. Moy Ni Ding died of unknown causes [19], and it appears that the couple’s two daughters may also have died at some point prior to 1931, as neither are listed in Moy Ni Ding’s own obituary [20][21].

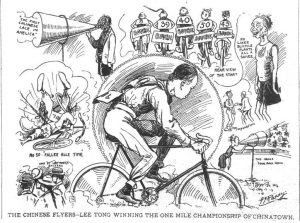

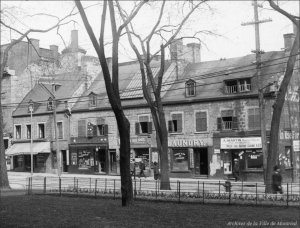

In 1918, Moy Ni Ding travelled to Montreal to meet and marry his second wife, whom he had married by proxy two years earlier [22][23]. The second Mrs. Moy Ni Ding, named Wong Shee or Phyllis Moy, was accompanied to Montreal from China by the 14-year-old Lan Moy [24]. The pair returned to Boston, where Phyllis soon became as involved in the Chinese-American community as her husband. One of the most successful merchants in Boston’s Chinatown, Moy Ni Ding was elected in 1924 as the president of the Boston Chinese Merchants’ Association—an organization that he also founded [25]. His illustrious community leadership also included roles as a founder and treasurer of the United States National Chinese Merchants’ Association; a councillor for the United Chinese Association of New England; the oldest member of the Boston Lodge of Chinese Masons; and the chairman of Troop 34 of Chinese Boy Scouts [26][27][28]. Phyllis served as vice-president of a Chinese Christian women’s association, the Order of King’s Daughters; president of the Chinese Women’s Club of Boston, and treasurer of the United Chinese Association [29][30][31][32]. The young William Moy was a trailblazer in his own right; while a student at English High School, he participated in track & field, football, and the swim team, and was the first Chinese boy to serve as staff for a student newspaper in Boston [33][34][35][36][37]. William went on to attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the first Chinese American from Boston Chinatown to do so, where he continued his academic and athletic pursuits [38].

Figure 2: William Moy, top right, with other members of the English High swim team (“School Swimmers Summoned to Shape Up for Coming Meets.” The Boston Globe, 30 Dec. 1915)

On June 5, 1931, Moy Ni Ding died in his sleep, reportedly “of hemorrhages,” at his home at 19 Harrison Avenue [39][40]. He had lived in Boston for more than 50 years, and his obituary in the Boston Globe referred to him as “the grand old man of Chinatown” and the “leading counselor for the Chinese in America” [41][42]. He was survived by Phyllis, William, and Lan Tue; his funeral included a procession of 120 cars, as well as the Boy Scouts of Troop 34 and eight of Moy Ni Ding’s cousins, who served as pallbearers [43][44].

** All birth dates are estimates as different documents list different dates.

Works Cited

[1][2][14][20][24][27][39][41][43] “Moy Ni Ding Dies in Chinatown Here.” The Boston Globe, 6 June 1931, https://www.newspapers.com/image/431252563/.

[4] “The Moys and the Chins Ventilate Their Grievances in the Court.” The Boston Globe, 6 April 1895, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430858597/.

[5] “Chins Foiled.” Boston Post, 7 April 1895, https://www.newspapers.com/image/74359375/.

[6] “Six Defendants Pay Fines.” The Boston Globe, 6 Nov. 1896, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430769521/.

[7][19][22] “Chinatown to Celebrate.” The Boston Globe, 30 April 1918, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430768546/.

[8] “Chinese Boy Seeks Seat.” The Boston Globe, 5 April 1913, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430934565/.

[9] “1900 United States Federal Census for Ni Diug Moy.” Twelfth Census of the United States, Massachussetts, Suffolk, Boston Ward 07, District 1245, p. 17, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7602/records/23980611?tid=&pid=&queryId=7cbfe700-500a-4390-b4ed-0a3bc0bd6303&_phsrc=xHA139&_phstart=successSource.

[10] Chapman, Mary, editor. Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

[11][16][17] “1900 United States Federal Census for Ni Diug Moy.” Twelfth Census of the United States, Massachussetts, Suffolk, Boston Ward 07, District 1245, p. 17, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7602/records/23980611?tid=&pid=&queryId=7cbfe700-500a-4390-b4ed-0a3bc0bd6303&_phsrc=xHA139&_phstart=successSource.

[12] “Births in the City of Boston During the Year 1896.” Boston, Suffolk, Massachussetts, United States records, www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G975-M972?view=index.

[13] “Births Registered in the City of Boston for the Year 1903.” Massachusetts, U.S., Birth Records, 1840-1915 for Moy Lan Tue, p. 1677, ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/5062/records/1585917?tid=&pid=&queryId=fdcf3b85-71fb-4cc4-8bc5-d4a3cc43ac60&usePUBJs=true.

[15] “Moy, “Chinatown Mayor” and M. I. T. Man, Dead.” The Boston Globe, 13 Aug. 1938, https://www.newspapers.com/image/431741753/.

[3][21][28][40][42][44] “Funeral Services for Moy Ni Ding.” The Boston Globe, 8 June 1931, https://www.newspapers.com/image/431254690/.

[23] “Wong Shee and Moy Ni Ding marriage record.” Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968, Presbyterian Knox Church, 1918, p. 14, ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1091/records/14059343?tid=&pid=&queryId=9ea25ed0-61cc-484c-89c5-1f348fd41d2b&_phsrc=xHA128&_phstart=successSource.

[25][45] “Moy Ni Ding Heads Chinese Merchants.” The Boston Globe, 24 Jan. 1924, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430300095/.

[26] “Chinese Enjoying New Year’s Fete.” The Boston Globe, 20 Feb. 1931, https://www.newspapers.com/image/436961271/.

[29] “Chinese Women Honor War Heroes at Public Reception.” The Boston Globe, 20 Sep. 1934, https://www.newspapers.com/image/431746128/.

[30] “Chinese Girls Sell Flowers, Buttons to Swell War Fund.” The Boston Globe, 23 Aug. 1937, https://www.newspapers.com/image/429071247/.

[31] “Chinese Here Pay Tribute to Bishop.” The Boston Globe, 28 Mar. 1939, https://www.newspapers.com/image/432250560/.

[32] Phyllis Ny (Wong Shee) Ding Moy Obituary, The Boston Globe, 16 Mar. 1959, https://www.newspapers.com/image/433681521/.

[33] “Around the Town.” The Boston Globe, 20 Feb. 1914, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430648005/.

[34] “English High Expected to Turn Out 150 Candidates for the Track Team.” The Boston Globe, 20 Jan. 1914, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430653801/.

[35] “Nine Jumps and the Shotput, Too.” The Boston Globe, 17 Mar. 1914, The Boston Globe, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430653961/.

[36] “School Swimmers Summoned to Shape Up for Coming Meets.” The Boston Globe, 30 Dec. 1915, https://www.newspapers.com/image/430900168/.

[37] “English High Scores 61 of the 93 Points.” The Boston Daily Globe, 30 Jan. 1915, https://www.newspapers.com/image/59030972/.

[38] “William Ding Moy.” China Comes to MIT: MIT’s First Chinese Students. https://chinacomestomit.org/first-boston-chinese.