Sometimes things in life come full circle sooner than we expect. In 2011 I was an undergraduate student at the University of British Columbia Okanagan. At this time in my academic career, I was quite honestly disengaged and truly at a cross roads where I desperately needed something to grab my attention and re-align my focus. Enter Professor Ainslie and his research program. At this time, October 2011, rumors were circulating that Prof. Ainslie would be leading a research expedition to the Nepal Himalayas to examine human adaptation to low oxygen levels. I vividly remember thinking to myself that maybe this was the break I needed, the academic substrate I required to re-ignite my passion for learning. As a young twenty year old man, admittedly still very naïve, I was luckily introduced to Prof Ainslie through a friend, whom I cannot thank enough today for facilitating my entry into research. As some would say, the rest is history… I went to Nepal in 2012 and upon my return to Canada and graduation from the Human Kinetics program I began my Masters of Science with Prof. Ainslie. Now as a PhD student in his lab, I recently took part in the more recent 2016 UBCO research expedition to Nepal. The end.

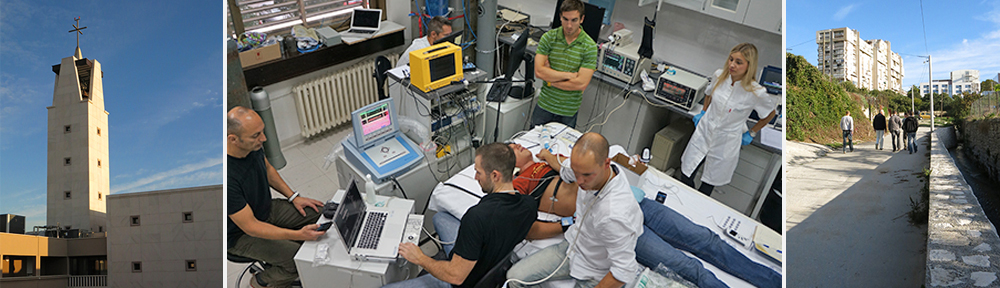

Wait! The story cannot end that fast! That would not do it justice, would it? Let us continue… Following my introduction with Prof. Ainslie in the fall of 2011 I began a research practicum in his laboratory. I remember spending as much time in the laboratory as I could, a human sponge absorbing every bit of information I stumbled upon. With the primary baseline study looming a mere day or two in the distance, I was asked to briefly leave the lab, while the research team had a private discussion. Standing in the hallway I thought to myself, had I made a mistake? Had I broken some equipment? What could possibly be so secret it required my absence to discuss? A few minutes later (although it felt like lifetimes) I was summoned back into the laboratory. To my surprise, and extreme excitement, I received an invitation to participate in the Nepal expedition! I said yes immediately. With my new sense of excitement and eagerness I returned to the lab two days later for a week of ~16 hour experimentation days.

The study I was now assisting with was pushing the envelope of human physiology research, and aimed to determine how changes in the oxygen content of our blood, as we would experience at altitude, affects oxygen delivery to our brain. Now, answering a question such as this is not a simple task. Specifics notwithstanding, the study involved catheterization of the radial artery (an artery in the wrist) and the internal jugular vein (a vein in the neck that drains blood from the brain). We needed a catheter in our neck… yes, our neck. Absolutely terrifying I thought. Who would subject themselves to such a study? Well, it was in fact the laboratory members that would be participating in this study – a group of modern day mad scientists that because of their passion for research and drive to “find the answer” conducted this testing on themselves. So I figured, why not? I could handle the so called “jug-line” and elected to participate in the study as well. Following completion of the dreaded jug-line study, the rest of the Nepal expedition went off famously, and was extremely successful.

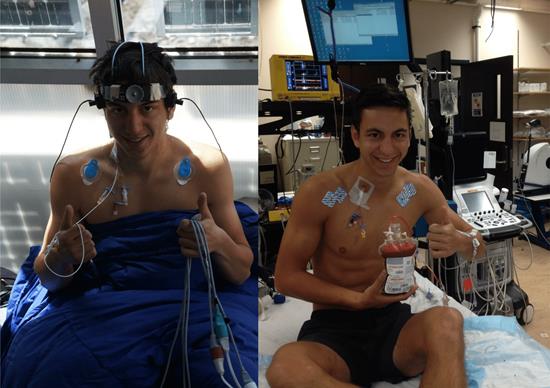

Catching my breath at the end of the “jug-line” study in 2012 (left) and 2016 (right). The internal jugular vein catheter can be seen on the right side of my neck in both pictures. I like to think that my passion for science and easy going attitude are clearly evident by the “thumbs up” attitude that I have carried with me from 2012 through to 2016. Photo credit: Dr. Chris Willie

Fast-forwarding to 2016, where as a PhD student I would be involved in my second Nepal research expedition, things began to come full circle, and I gained a new sense of perspective from that I had in 2012. This time around, I had a serious job to do. Instead of merely helping out with the main study, it was my job to lead it, my main doctoral thesis study. As you can see in the picture above, I am holding approximately half a liter of my own blood, or the “house red” as our study physician called it. Why you might ask? Well, we decided to ask the question, how does the red blood cell contribute to regulating oxygen delivery to the brain when we have lower blood oxygen levels? Clearly the red blood cell is important as it carries oxygen around our body and delivers it to our tissues like a tireless postal service (brain, heart, etc.). However, there is some idea it also regulates how much flow is directed to different areas of our body, including the brain. In order to answer our question, we subjected ourselves to lower levels of oxygen using a computer controlled breathing system (simulating high altitude at UBCO) in our normal state, and then following a dilution of our blood, hence why my blood was removed and put into a bag. Simply put, the difference in how our body responded before we removed the blood, and after it was removed indicated how important the red blood cell is and let me tell you it is pretty important! This study was completed successfully and preliminary analysis has provided us with some invaluable information.

Alongside running my main thesis study, I was tasked with several large leadership roles for the overall expedition. Long days of ordering supplies, equipment, and then organizing everything into an expedition manifest were pushing my organizational skills to the limit. Had you seen how disorderly my workspace was at the time you may not have thought I was the best option for the job! However, we successfully transported approximately six tons of equipment to Nepal and the pyramid lab.

Following the safe arrival of our 37 member team and all our equipment in Kathmandu, the real excitement began. As opposed to 2012, where the chaos and proverbial buzz of Kathmandu was rather alarming, I exited the airport with a more seasoned sense of calm. I was back and I was excited. No longer the undergraduate student lacking direction and passion, I had matured, focused, and arrived with a sense of determination. Therefore, while impossible to replicate my initial introduction to Nepal, a greater sense of appreciation for who and where I was, alongside the opportunity to draw parallels between the two expeditions and self-reflect made the journey ahead one of both scientific and personal significance.

Cross-checking the equipment with the expedition manifest upon arrival in the Kathmandu Airport. Although I don’t vividly remember this particular moment, a colleague of mine, Dr. Chris Willie, jokingly informed me following the expedition that my level of focus is beautifully illustrated by the juxtaposition of my very still self and the blurred airport worker behind me. It was quite the relief when all the equipment arrived in one piece! Photo credit: Dr. Chris Willie.

Over the course of approximately one week in Kathmandu the rest of the crew and I spent our days managing a rather sporadic schedule of work, exploration, and gastrointestinal distress. Our testing on the high-altitude native population, the Sherpa, was just beginning. This line of inquiry was quite intriguing to me, as it provides a window into how humans evolve during low oxygen levels. Sherpa, to explain, have lived at high-altitudes for over 25,000 years, and as a result of positive adaptation perform exceptionally in the hostile low oxygen environment of the Himalayas. In truth, the Sherpa are the unsung heroes of Himalayas, and the backbone of most modern day expeditions. I was intrigued by the prospect of furthering our knowledge of why the Sherpa have become so fit for life at altitude. I wanted to know if the brain of the “oxygen adapted” Sherpa reacted differently to low oxygen levels than did the brains of us westerners upon ascent to altitude. This question was my focus throughout the ascent.

Top left is the beautiful Kathmandu Guesthouse courtyard, which we called home for a week prior to ascent. Ticket in hand we flew over mountain ranges sprinkled with villages until landing in the rugged and dangerous Tenzing-Hillary Airport in Lukla. Photo credit: Dr, Alex Williams and Ryan Hoiland

The ascent commenced by taking a flight to the most dangerous airport in the world, the Tenzing-Hillary Airport in Lukla, 2840m above sea-level and located on the side of a cliff. The runway is about 500m in length, and slanted at an approximate 12 degree angle. This apparently requires the pilot to fly below the level of the runway, so that upon the approach he or she may pull up and land the plane parallel to the runway. While not an expert, I understand that flying straight at a cliff until the final possible moments is not a fail-safe procedure. To add some perspective the runway at Kelowna International Airport is over 5 times longer than the runway in Lukla. Upon landing, we met with our Nepali coordinator, or Sirdar as they are referred to, Nima Sherpa (pictured below) to coordinate equipment, and a much needed meal and rest.

Nima Sherpa, our expedition Sirdar summited Mount Everest in the summer of 2009. While critical to the organization and execution of our expedition, Nima’s greatest trait may have been is ability to fill a room with laughter, always joking and boosting team moral. Photo credit: Ryan Hoiland.

The next 10 days involved trekking to Monjo (2800m), Namche Bazar (3400m), Deboche (3900m), Pheriche (4370m), and the Ev-K2-CNR Pyramid Laboratory (5050m). At each location we collected data, a struggle due to the variable and overall sparse access to steady electricity. Luckily, we had a well versed tradesmen on the team to keep our operation running. Namche is one of my favourite locations in the world. Sitting amidst the Himalayan mountain range, 3400m above sea-level, it is the epicenter of the Mount Everest trekking region. Drastically changed from 2012, it is now littered with cafes, bakeries, and pubs – for better or for worse. It is perhaps worth noting that without exception, no matter where I travel in the world I always stumble upon an Irish pub. This, I find, is quite remarkable, and perhaps influenced why the team and I were so fond of Namche (they had cold Guinness!). But in all honesty, Namche, and the Himalaya in general, were a welcome departure from the day-to-day grind we are so accustomed to at home. With a cup of burnt espresso in hand and my eyes focused on the breathtaking landscape surrounding me, I had not a care in the world.

Connor Howe and I receiving some supplemental oxygen during one of our ascent studies. Thumbs up for oxygen! Photo credit: Ryan Hoiland

Namche Bazar located at 3400m above sea-level is the largest village on the Mount Everest Base Camp trail. Built along the side of the mountain, this crescent moon shaped village felt like a metropolis in the mountains. Photo credit: Dr. Alex Williams.

Onwards and upwards, now breaking the 4000m mark, we arrived in Pheriche on day 7 of our trek. In general it is around 4000m where it becomes more-or-less obvious who will succumb to altitude illness. Given the impossibility of predicting who would get sick prior to ascent this made for a bit of suspense. Headaches were evident throughout the entire group, myself included, but no one had yet to progress beyond that. While near impossible to predict who will get altitude illness, the most telling sign, is whether or not you were sick in a previous trip to altitude. Therefore, the knowledge that I experienced negligible levels of altitude illness in 2012 kept me at ease, while I observed the rest of the team out of curiosity and concern.

Pheriche holds one of my fondest memories of the trip. We were in Pheriche on October 10th and October 11th, which were Mike Tymko and I’s birthdays. Following dinner on October 10th, we were each surprised with a birthday cake, that I have to admit was quite fantastic. As Mike and I were away from home on our birthdays the year prior as well, at the Barcroft Station, on White Mountain, California, it was nice to enjoy some festivities this year. Now believe me, a chocolate cake at 4000m above sea-level is about as festive as it gets when all you have eaten for the past 2 weeks is potatoes, lentils, and rice! It was an enjoyable night spent with some great friends.

Pheriche, 4371m above sea-level is a small village comprised of about 10 lodges and the Himalaya Rescue Association clinic. Photo credit: Dr. Alex Williams

At last, we reached the daunting task of our final ascent to the Pyramid Laboratory, trekking above 5000m. The steepest, and highest portion of the trek, I was ready to embrace the physical challenge. While I struggled immensely in 2012, I was in better physical shape in 2016, and ascended much easier, and without complete exhaustion.

The Ev-K2-CNR Pyramid Research Laboratory. Our arrival took place on a beautiful and sunny day. Photo Credit: Ryan Hoiland.

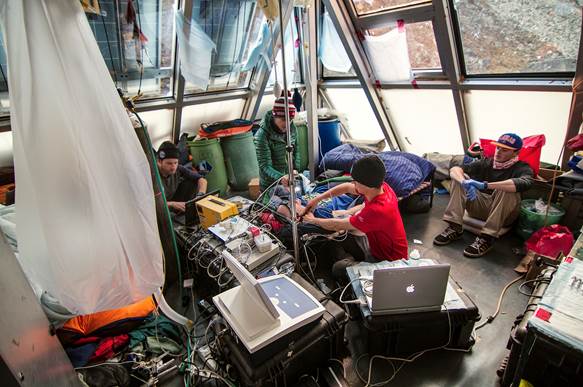

While the team took a moment to absorb the fact we had finished our ascent, I remembered back to my arrival in 2012. Exhausted, irritable, and completely unaware of what the future held. I chuckled to myself thinking, who knew I would be back again. Following this short period of calm, it was time to get back to business. It was but a small group of us, ten I believe, that actually arrived a day early with the task of setting up the labs. From that point onwards, it was long days, starting at 5am, and often ending at about 8pm, all the while carrying a little bit of altitude illness with us, which I might add feels quite similar to a hangover! We ran more studies on the, brain, heart, lungs, nervous system, skeletal muscle, and our blood vessels. Every day was unique in its own way, whether it was due to a power outage, a meal other than dahl baht, or an electrical fire. Now, given we were at a fairly high-altitude, team members began to intermittently battle bouts of rather debilitating altitude illness. Unfortunate for one member of the expedition, their symptoms did not resolve despite treatment with altitude medication, and they had to descend – the only true treatment for altitude illness. So for three weeks we worked away, completing a multitude of studies with a fantastic success rate. At the end of all the hard work was a day scheduled to explore the Khumbu region, trekking to both Everest Basecamp and to the top of Kala Patthar (pictured below).

Setting up the transcranial Doppler ultrasound in our study, which looked at the role of the red blood cell in oxygen delivery to the brain at altitude. Pictured with me is Matt Rieger (left), Alex Hansen (back middle), and Connor Howe (right). Photo credit: Dr. Alex Williams.

The view atop Kala Patthar is an unforgettable one. Standing there, my gaze fixated on Mount Everest, everything else felt so small and insignificant. Detached from everyday societal burdens, I got to enjoy the beauty of our wonderful world.

Looking from Kala Patthar onto the Khumbu icefield and Mount Everest in the background. It was a perfect day for our trek. Photo credit: Daniela Flück.

The 2016 Nepal expedition was an amazing experience, and invaluable to my progression as a PhD student. Since our return, several team members have already submitted their research for publication. I am almost there too! In fact, nearly every student from the expedition presented their research that the International Hypoxia Symposium, in Lake Louise, Alberta, in February this year (2017). It was an amazing conference and platform for us to showcase the work we had just conducted. I was lucky enough to be awarded 1st Place for best oral presentation by a junior scientist, for my presentation on how the red blood cell is important in regulating oxygen delivery to the brain. While we are still working with the mountain of data we collected in 2016, our eager and inquisitive minds are already looking forward to the next adventure!