The history of music printing and publishing is technical, social and artistic[1]. Its technical history revolves around the solution to representing music as visual symbols. Its social history encompasses how tastes, styles and audiences have changed the scope of what music has been produced. The artistic component reflects the history of musical typography.

Principle Techniques of Music Printing[2]

Music printing has three main techniques: music-type, engraving and lithography. A fourth technique has developed recently over the past 30 years in music-processing software. The majority of music published today is printed via lithography and its photographic processes.

Created in the mid-15th century by Gutenburg, music-type evolved much like movable type for text. The design for a note, rest or clef is cut into a punch made of steel. A matrix is produced by striking the punch into a metal bar. The type is cast matrix is inserted at the base, and molten lead is poured in. The mould is taken apart and the type remains. The notes and symbols are assembled together by a compositor following a manuscript. Using a composing-stick, the compositor transfers the music type line by line into the machine. Early music required relatively few sorts, or separate notes, but by the 19th century, music hadinto a mould. Thedeveloped so much that a case of music-type could contain up to as many as 400 sorts[3]. Printing via music-type became increasingly difficult, time-consuming and costly; musical knowledge was also required the compositor. Although it initially flourished in Europe and America, this printing method grew out of favour and became obsolete in the mid-20th century. Music woodblock printing also developed later in the 15th century, alongside woodblock illustrations to accompany text, and was quite popular in the 16th century. The first surviving example of music-type print is the Constance Gradual (c. 1743)[4].

Created in the mid-15th century by Gutenburg, music-type evolved much like movable type for text. The design for a note, rest or clef is cut into a punch made of steel. A matrix is produced by striking the punch into a metal bar. The type is cast matrix is inserted at the base, and molten lead is poured in. The mould is taken apart and the type remains. The notes and symbols are assembled together by a compositor following a manuscript. Using a composing-stick, the compositor transfers the music type line by line into the machine. Early music required relatively few sorts, or separate notes, but by the 19th century, music hadinto a mould. Thedeveloped so much that a case of music-type could contain up to as many as 400 sorts[3]. Printing via music-type became increasingly difficult, time-consuming and costly; musical knowledge was also required the compositor. Although it initially flourished in Europe and America, this printing method grew out of favour and became obsolete in the mid-20th century. Music woodblock printing also developed later in the 15th century, alongside woodblock illustrations to accompany text, and was quite popular in the 16th century. The first surviving example of music-type print is the Constance Gradual (c. 1743)[4].

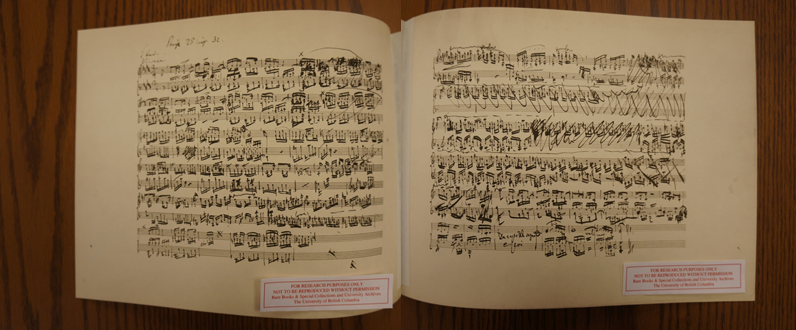

Music engraving developed in the 16th century and became extremely popular in the 17th century. The process involved a burin which was used to engrave the music onto a copper plate and then etched with acid. Music engraving was highly preferred to movable type since it allowed for more complex notations. Working in mirror image from a manuscript, the engraver first draws lines with a five-pronged score for the staff. Second, punches are used to stamp text for tempo indications and expressions along with clefs, key signatures, rests and accidentals. Last, but not least, the notes are added in. The earliest known example of music-engraving is present in the Intabolatura da leuto del divino Francesco da Milano (c.1536).

Lithography was developed in the early 18th century by Alois Senefelder. The process is based on the principle that grease repels water; an image can be inked onto a metal plate and transferred onto a surface. Unlike engraving, lithography does not produce crisp marked edges but well-inked printers can still produce sharp images. The lithographic process became the quickest, cheapest and most efficient way to print music, and was taken up by the principle musical printers of the time; Schott of Mainz, Breitkopf of Leipzig, and Ricordi of Milan. Wagner famously wrote his Tannhäuser opera on lithographic transfer paper.

Recently, there have been developments in the digitization of music print. Notation software programs such as Score, Notewriter, Finale and Sibelius have been making headway in this new industry. These advances have changed music printing and publishing, but are nowhere near as developed as word processors are for text.

History of Music Print in Europe[5]

The early history of music print is closely related to the development of print. Gutenberg’s invention of movable type in 1440 transferred over easily into music print. The two dominant styles of typography or notation used around this time were the Gothic and the Roman. The former was preferred by German-speaking parts of Europe, while the latter was used most in Latin countries including England and the Netherlands. The earliest examples of music print are from the Latin incunabulum including the Constance Gradual. It was printed from two impression from music type in Gothic, characterized by the diamond-shaped notation, and rubricated initials in red.

By the late 15th century, Venice had become the central hub of Italian printing. Petrucci obtained the exclusive rights to print canto figurato music. His perfections in music-type spread throughout Europe: Attaingnant in France followed suit in the 16th century, establishing himself as a prominent bookseller and the first music publisher to operate on a large scale. His business was carried onwards by Le Roy & Ballard, whose music type was distinctly rounder than the ones before it. They became a leading publishing house well into the 18th century. By the mid-16th century, many music publishing houses had sprung up, most notably in Antwerp, which became the centre for thepublishing trade.

English music publishing flourished mid-17th century in the houses of the Playfords and the Walshes. The latter publishing house, in particular, was known for developing cheap speedy print techniques. By the mid-18th century, Leipzig had become the centre of music publishing as a result of German typefounder and printer Breitkopf’s music type. Leipzig would remain a prominent figure in music publishing business despite houses establishing in other cities, particularly Vienna, until after the Second World War.

History of Music Publishing in Europe[6]

A large part of printing and publishing in music was made through agreements between composer and publisher. Attaingnant, working in the 16th century, offered little in terms of financial payment to his composers, but printed an agreed number of copies which brought them honour and fame. Copyright protection had not yet been implemented and composers such as Haydn and Beethoven felt taken advantage of. Haydn, for some time, corresponded with the Viennese printing of Artaria but switched over to Breitkopf & Härtel. Mozart was the opposite: his father failed to interest Breitkopf & Härtel early on and turned to Artaria to publish his chamber works. Publishers before the 21st century had to be “adaptable, diplomatic, experimental, businesslike, and above all sensitive to emerging gifts and talents and to the changing patterns of the musical scene”.

With the turn of the 21st century, new technological developments have changed the focused on copyright laws and performing rights. The music publishers’ income comes principally from performing-right fees, mechanical reproduction fees, royalties, hire fees, and the sale of music. The composer’s income is derived from royalties on copies of music and fees accruing from performances. Copyright is typically owned by the publisher in the duration of the composer’s lifetime and 70 years after death. The royalties paid to the composer immeasurably less than incomes earned in the 19th and 20th centuries while publisher incomes are continually being eroded by illegal photocopying and the like.

History of Music Printing and Publishing in Warsaw

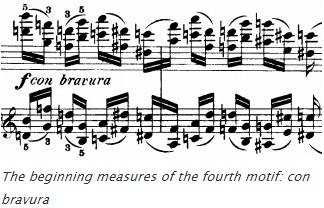

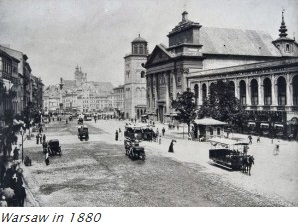

Prior to 1795, Poland’s music industry was only easily accessible to the aristocratic and wealthy, all of whom represented only a small portion of the population[7]. Poland’s partitioning and loss of independence around 1795, however, only ignited the rise of Enlightenment ideals which lead to a major change in the music publishing industry in its capital Warsaw[8]. While political instability rocked the country, the music printing industry flourished and expanded well into the 1820’s. Early 19th century Warsaw faced a period of increased demand for music by the bourgeoisie. Among the many that began opening music engraving shops included Elsner and Cybulski[9]; the latter published Chopin’s first published work, Polonaise in G Minor. Besides the increased production in pianos and the rising presence of musical institutions, dance music, especially in the ballroom, also featured prominently in this era[10]. Chopin grew up in the heyday of these popular forms and their features undoubtedly influenced his composition of waltzes, polonaises and mazurkas during his early years. Non-dance music was also fairly popular around 1810-1830[11]. Forms such as marches, nocturnes, romances, études and preludes sprung about, many of which Chopin experimented with. During the Uprisings, nationalism flowed through the country in the form of music in operas and fantasias featuring patriotic themes. Following the fall of the Uprising, Poland suffered decades of extreme censorship[12]; the music printing industry suffered as well. It would take a long time for Warsaw to return to its prosperous music printing years during Chopin’s youth.

Prior to 1795, Poland’s music industry was only easily accessible to the aristocratic and wealthy, all of whom represented only a small portion of the population[7]. Poland’s partitioning and loss of independence around 1795, however, only ignited the rise of Enlightenment ideals which lead to a major change in the music publishing industry in its capital Warsaw[8]. While political instability rocked the country, the music printing industry flourished and expanded well into the 1820’s. Early 19th century Warsaw faced a period of increased demand for music by the bourgeoisie. Among the many that began opening music engraving shops included Elsner and Cybulski[9]; the latter published Chopin’s first published work, Polonaise in G Minor. Besides the increased production in pianos and the rising presence of musical institutions, dance music, especially in the ballroom, also featured prominently in this era[10]. Chopin grew up in the heyday of these popular forms and their features undoubtedly influenced his composition of waltzes, polonaises and mazurkas during his early years. Non-dance music was also fairly popular around 1810-1830[11]. Forms such as marches, nocturnes, romances, études and preludes sprung about, many of which Chopin experimented with. During the Uprisings, nationalism flowed through the country in the form of music in operas and fantasias featuring patriotic themes. Following the fall of the Uprising, Poland suffered decades of extreme censorship[12]; the music printing industry suffered as well. It would take a long time for Warsaw to return to its prosperous music printing years during Chopin’s youth.

Continue reading →