Étude Op. 10 No. 3 in E Major was composed in August of 1832 by Frédéric Chopin. It was first published in French, German and English. It has been nicknamed Tristesse for its slow cantabile melody.

Composition

The set of études in Op. 10 was composed by Chopin in the 1830s and published in 1833. Chopin dedicated the twelve études to fellow composer and friend Franz Liszt[1]. Étude Op. 10 No. 3 in E Major, composed in August of 1832, is one Chopin’s most popular and well-loved études. Because of its cantabile ((It.) in a singing style[2]) melody, it has earned many nicknames including Tristesse((Fr.) sadness, sorrow, melancholy[3]). As such, it has also been compared to the style of Chopin’s nocturnes, which feature lyrical melodies. Étude Op. 10 No. 3 was originally set in tempo to vivace ((It.) vivacious, fast and lively[4]; original score), appended with ma non troppo ((It.) but not too much[5]; French manuscript) and eventually changed in print to lento ma non troppo ((It.) slowly[6], but not too much), the latter most of which has been retained in modern editions where the metronome is specified at 100 to the eighth note[7].

Structure & Stylistic Traits

Like his other études, Op. 10 No. 3 is written in ternary form (ABA), characterized by three parts with the second half of the A section returning again at the end in a shortened form[8]. The polyphonic texture of the piece, particularly in the A sections, displays three voices[9], requiring the performer to bring out the melody in the top line with the right hand while simultaneously providing accompaniment with the left hand. In practice, the right hand should lean slightly more to the right to bring out the melody on top[10].

The middle section, poco più animato ((It.) a little more animated, lively[11]) features five different eight-bar motifs, the first of which is animated and bright (21-24), repeated and transposed in bars 25 through 29. The second motif features irregular rhythms and a lilting melody highlighted by jumps in sixteenth notes (30-31) followed by inversions of diminished sevenths (32-33). This motif, like the first, is also transposed in its second half (34-37). A darker third motif follows (38-45), characterized by a sequence of diminished fifths and augmented fourths in both hands.

The middle section, poco più animato ((It.) a little more animated, lively[11]) features five different eight-bar motifs, the first of which is animated and bright (21-24), repeated and transposed in bars 25 through 29. The second motif features irregular rhythms and a lilting melody highlighted by jumps in sixteenth notes (30-31) followed by inversions of diminished sevenths (32-33). This motif, like the first, is also transposed in its second half (34-37). A darker third motif follows (38-45), characterized by a sequence of diminished fifths and augmented fourths in both hands.

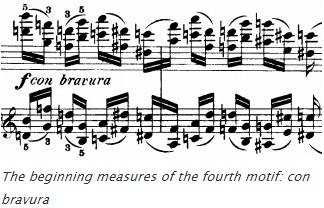

The fourth motif, con bravura ((It.) with skill, brilliance[12]), reaches the climax of the piece with eight bars (46-53) of double sixths for both hands, finally culminating on an extended dominant seventh from bars 52 to 53. The section is marked with two-note slurs requiring extensive practice in the up and down contrary movements of both hands. The fifth motif transitions back a tempo ((It.) return to the previous speed) featuring trills in the left hand, returning once again to a polyphonic three-voice structure, and gliding into a restatement of a shortened A section.

Technical Difficulties

While relatively short, the piece is technically difficult, especially in its faster sections, and requires what Clarke calls “Bachian clarity”[13], crisp, yet lyrical, fingerings required for Bach’s pieces. The main technique being studied here is legato ((It. smoothly[14]) playing and syncopation[15]. There are no pedal markings in the original, which is meant to suggest that the etude is intended to be played legato throughout with little to no use of the pedal. According to Hipkin[16], Chopin employed the pedal a great deal in his pieces, explaining why many modern editions of this etude include pedal markings. The Pleyel piano for which Chopin composed, however, differs greatly from the modern piano[17]; players should be wary and conservative in their pedal use. The syncopated double notes in this piece also require sufficient clarity and speed; playing at mezzopiano ((It.) moderately soft) with as little excess movement as possible will allow the appropriate velocity for which the piece demands[18]. Huneker and Bauer also note that this piece requires the use of rubato ((It.) robbed time[19]), wherein the player can indulge some artistic tempo license for a more expressive quality. Comments on Chopin’s own use of rubato stress the importance of tasteful tempo rather than maintaining a strict rhythmic pulse.

First Edition Publications

There are three first editions of the Op. 10 manuscript from which Étude Op. 10 No. 3 belong: French, German and English. The French manuscript was printed in June of 1833 in Paris, published by Maurice Schlesinger. The first impression of this manuscript was used to prepare subsequent German and English versions, hence the erroneous “J. Liszt” dedication present in all three first editions[20]. The German edition was printed in August of 1833 in Leipzig, published by Fr. Kistner. The English edition was printed around 1835-36 in London, published by Wessel & Co. with added dedicatees Ferdinand Hiller and Julian Fontana. All three versions feature engraved musical text with varying types of covers. The German and English versions, unlike the French, divide the études into two volumes, Nos. 1 thorough 6 in the first, and Nos. 7 through 12 in the second.

[1] Huneker 133

[2] Music Theory: cantabile

[3] The Canadian Oxford Dictionary (2 ed.): tristesse

[4] The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music: vivace, vivacemente

[5] Music Theory: ma, non, troppo

[6] Music Theory: lento

[7] Bauer 15

[8] The Oxford Companion to Music: ternary form

[9] Our Chopin

[10] Bauer 15

[11] Music Theory: poco, più, animato

[12] Music Theory: con, bravura

[13] Clarke 315

[14] Music Theory: legato

[15] Piano Society

[16] Bauer 8

[17] Bauer 8

[18] Bauer 16

[19] The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music: rubato

[20] Chopin’s First Editions Online