English: collotype (Albertype, Albert-type, artotype, phototint, photogelatin, hydrotype, ink-photo, autogravure, etc.); French: phototypie; German: Lichtdruck[1]

Derived from the Greek word kola meaning glue, the collotype process requires printing from a gelatin surface in a lithographic manner as compared to intaglio and relief printing. This form of photomechanical printing creates accurate reproductions. It was invented by Alphonse-Louis Poitevin in 1855 and first used in 1859 by F. Joubert. Important improvements were introduced in 1868 by Joseph Albert and Jakub Hunsnik[2].

Print Process

Specifically, the collotype process is a screenless photomechanical process that allows high-quality prints from continuous-tone photographic negatives. Using heat and cold water treated dichromate-sensitized gelatin, a random surface micropattern is created that, once exposed to UV light, hardens, becoming more hydrophobic under light area and remaining hydrophilic under darker areas. The hydrophobic parts receiving more light will hold more ink since water and oil do not mix well. This matrix can then be inked and printed using a rotary flatbed or rotary graphic press[3].

History & Technological Improvements

In 1855, Poitevin patented collotype printing, which was first successfully used in the June 1860 issue of The Photographic Journal by Joubert in 1859. Similar methods were explored in 1865 by du Motay and Marechal using a copper plate as the substrate. Problems with the adhesion of the gelatin to the copper plate limited runs to no more than 100 prints. This was greatly improved in 1868 by Albert and Husnik via applying a subbing layer of thick glass coated with gelatin[4]. This increased runs to 1,000 prints and variants years after improved the durability of the substrate and the speed of printing. In 1874, Joseph Albert introduced the three-color collotype process using continuous separation. In 1922, Robert John introduced the Aquatone process using halftone negatives in the preparation of the collotype plates. This was followed by the development of the Optak and Triton processes in 1946 and 1955. Several attempts have also been made to replace the gelatin with synthetic polymers; however, these have proved to be unsuccessful. The collotype process remains technologically challenging and expensive and has since been replaced by faster and cheaper offset lithography. As of 2010, very few collotype print facilities are still in print[5].

Identification & Variants

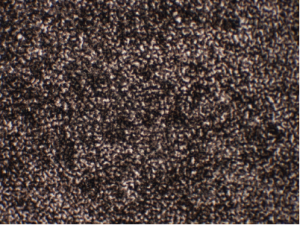

The collotype process was used for short-run printing editions from photographic negatives. To the untrained naked eye, it looks like a black-and-white photograph, but with a powerful microscope, the image will look as if it is made up of tiny polygon grains. Often, collotype prints will be coated with varnish to achieve the look of real photographs[6]. Shellac varnish is most commonly used. ATR-FTIR analysis will detect and identify the presence of varnish or surface coatings. Many variants exist to the collotype process, the most important of which are halftone and colour collotypes[7].

[1]The Getty Conservation Institute 4

[2] GCI 4

[3] GCI 5

[4] GCI 5

[5] GCI 5

[6] GCI 8-11

[7] GCI 15