Author: Chrisanne Kouzas. Posted: Oct 15, 2010 (Links Updated: Feb 26, 2024)

About a year ago, one of my Canadian classmates asked me a strange question: “What’s that loud buzzing sound in the background of all the FIFA Confederations Cup matches? It’s so annoying!” It took me a moment to realize what he was talking about, and then I clicked: vuvuzelas. “A vuvu-what?” he replied when I answered his question, “what is that?” My classmate, like most of North America at the time, had never seen (or rather heard) a vuvuzela before, but this was all about to change with South Africa being the host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. A few months later when I flew back to Johannesburg for the world cup, the same classmare wished me a good trip and sent me back with one request: “Please get me a vuvuzela!”

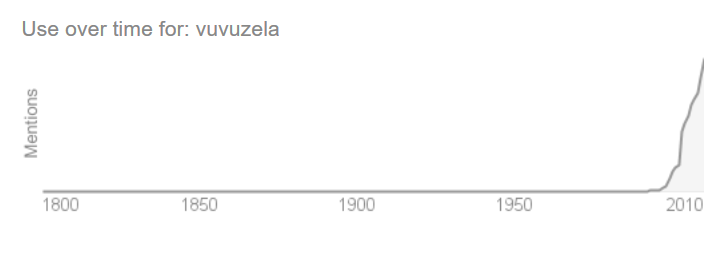

Thanks to the 2010 FIFA World Cup, the Vuvuzela has now taken the world by storm and become the icon of South African soccer culture. Soccer fans worldwide can’t wait to get their hands on vuvuzelas, and even people who don’t watch soccer want to own one. For those who don’t have access to a physical vuvuzela, there is always the vuvuzela app, or this ten-hour-long vuvuzela soundtrack on YouTube. Here in Vancouver, vuvuzelas have been in such high demand that their first shipment, which arrived just before the start of the world cup in June, sold out in one day.

As someone who grew up in South Africa, the recent international obsession with vuvuzelas has fascinated me. Until the 2010 FIFA World Cup, I never really gave vuvuzelas a second thought – they were simply a part of every day life. When we had sports tournaments at school, everyone brought vuvuzelas. When there was a local or national soccer tournament, everyone brought vuvuzelas. When there were strikes or protest marches in the city center, everyone brought vuvuzelas. My subconsious had become so accustomed to the sound of the vuvuzela, that I didn’t even notice the “annoying buzzing” pointed out by my classmate during the FIFA Confederations Cup. Little did I know that the vuvuzela would soon become impossible to ignore.

In the South Africa of yesteryear, vuvuzelas could only be bought on street corners from local vendors, and they all had the same simple plastic design – colourful, but basic. But when I arrived back in South Africa for the world cup, vuvuzelas were being sold everywhere – at the airport, in malls, supermarkets, restraunts and gas stations – and these were not the same basic plastic vuvuzelas I had grown up with, no sir. These chic new vuvuzelas were available in any colour, shape or size – ranging from gigantuan vuvuzela figurines on display at world cup events, to tiny vuvuzela souveneirs to take back home. Many incorporated flag colours of competing countries; others had elaborate designs, encrusted with expensive jewels and feathers. Rumor has it that a Russian businessman even paid £20 000 to have a personalized vuvuzela made to accompany him to the final match- plated in white gold and encrusted with a giant diamond in its centre.

What fascinated me most was how the vuvuzela became popular overnight without any form of advertising. Having just spent time in Vancouver for the 2010 Winter Olympics, an immediate comparison that came to my mind was the similar popularity of the Hudson’s Bay Red Mittons. Although the mittons and the vuvuzelas shared the same iconic status during their respective sporting evenets, a key difference was that in contrast to the humble origins of the vuvuzela on the street corners of South Africa, in Canada, there was a formal, nationwide campaign to market and popularize the mittons sold by Hudson’s Bay, the official sponsor of Team Canada’s olympic gear.

Usually we see companies designing products and designing targeted campaigns to encourage sales, but in this case, the situation was reversed – companies began exporting vuvuzelas around the world because demand for the product was so high – no marketing needed. When tourists started arriving in South Africa for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, they encountered the vuvuzela as authentic part of the local soccer culture – sold at matches accross the country, vuvuzelas became an immediate way to particpate in the host country’s soccer traditions, while also making excellent souveniers to take home as presents – cheap, lightweigh and easy to transport. And without much thought to it, suddently the vuvuzela became the sound of South Africa and the FIFA 2010 World Cup, and global vuvu-mania ensued.

Despite its global popularity, the noise levels that were demonstrated during the 2010 FIFA World Cup prompted various sporting organisations to ban the vuvuzela at future events and venues. However, FIFA continued to permit their used in stadiums throughout the 2010 FIFA World Cup, with President Sepp Blatter arguing that FIFA “should not try to Europeanise an African World Cup … that is what African and South Africa football is all about – noise, excitement, dancing, shouting and enjoyment.” This sentiment resonated accross the country, with commentator Farayi Mungazi emphasizing that “banning the vuvuzela would take away the distinctiveness of a South African World Cup [that is] absolutely essential for an authentic South African footballing experience.”

Personally, I couldn’t agree more. Hate it or love it, when in South Africa, you gotta do the Vuvuzela!