Given his commute takes an hour and a half each way, Nathan Pachal has a lot of time to think about how to change the region he passes through every day – and how to change the journey itself. He starts in Langley on a bus that lumbers through heavy traffic before he boards the SkyTrain that takes him to Vancouver, where he finishes his journey with a ten-minute walk to work.

He thinks speeding up commutes like his by expanding the rapid transit system is the best way to get this region moving – but it’ll cost $6.5 billion. And he wants to convince his neighbours that it’s worth every penny; after all, it’s no more costly than building new bridges like the new Port Mann and Golden Ears, and the upcoming George Massey.

Pachal isn’t a politician or an urban planner, but a 30-year-old broadcast engineer who decided to do what noncommittal politicians were too timid to do, by putting together his own regional transit plan – in his spare time. It’s a fully costed plan to pay for 38 kilometres of SkyTrain and light rail lines, eight new express bus routes, a gondola, and upgrades to the existing network – which he says are all sorely needed.

“No one else had done anything about it. Someone had to do something,” he says.

Filling the leadership vacuum

Pachal spent a year working on his plan with a fellow transit advocate, blogger, and all-around public policy wonk, 24-year-old Paul Hillsdon from Surrey. They released their plan last August, sparking coverage from mainstream media and enthusiastic support from much of the urban planning community. It was seen as the first comprehensive document that outlined a way to fund much-needed transit improvements in the region.

Pachal and Hillsdon are among dozens of young people toiling away to promote public transit, and trying to fill what they see as a “leadership vacuum” at a pivotal time for transportation planning in the region. Pachal thinks a proposal like theirs should have been put together by political leaders, instead of being left to two bloggers with matching black glasses, both skinny and fresh-faced enough to pass for college freshmen.

He thinks the region doesn’t have any other options but to expand rapid transit. “It’s really a matter of economic growth and quality of life,” he says, adding it’s the only way to accommodate the extra million people who will fill up the region – and its transportation network – over the next three decades. “And there’s simply no more room for more roads,” he says.

Their plan has been gaining traction now that those in the know are gearing up for an upcoming referendum on transit the provincial government has mandated for the region – although no one really knows when it will happen, what the question will be, or if it will happen at all. Hardly anyone even wanted the referendum in the first place, it seems.

An evasive election promise

The idea for putting transit funding to a vote was one rarely-mentioned part of the election campaign of Christy Clark’s BC Liberals in spring 2013, one little idea that got lost in the fray. Their platform papers mentioned a need for new funding sources for transit expansion, and said that any new revenue sources would be subject to a special vote. Most pundits were predicting the premier would be voted out of office, so that one bullet-point largely slipped under the radar.

Pachal says he thinks the Liberals opted for a referendum to get out of addressing transit funding head-on, and hoped that by postponing the decision, and leaving it up to the people, their record on transit wouldn’t cost them an election.

“Transit was looking like it could become an election issue, so they said ‘Okay, we’ll have a referendum, so now it’s not an election issue, and we don’t have to worry about how we’re going to pay for transit,’” Pachal says.

Candidates from other parties called the referendum plan wasteful and accused the Liberals of shirking responsibility, but transportation never became one of the big-ticket issues in election coverage. Apparently, the strategy worked, and the Liberals were elected on that platform, referendum plan and all. And because they made the promise, they had little choice but to follow through with it.

By and large, transit advocates don’t want this referendum, as they say politicians get elected to make these hard decisions themselves, and should just hurry up and find the money for transit improvements. The Liberals have been accused of passing the buck to the electorate, and further delaying the infrastructure improvements bus riders have long been clamouring for.

Clark and her transportation minister, Todd Stone, have at times contradicted each other as to what they intend the referendum to be. During the campaign period, the former transportation minister said the ballot would offer a choice of which new funding tools to implement, before Clark contradicted her by saying there would also be a ‘none-of-the-above’ option. Stone, who became Minister of Transportation in June 2013, has been saying that we just don’t know yet what the question will be – and that it will be largely up to the mayors, anyway.

And then what if voters are scared off by talk of costly new taxes? Some transit buffs are concerned the average car driver won’t want to pay to fix someone else’s problem. And if the public says “No” after a vote, that could spell disaster for the prospect of getting any new rapid transit lines for decades to come.

The future of a region at stake

Gordon Price, a former Vancouver city councillor who now leads SFU’s City Program, is a bit of a doomsayer when it comes to Vancouver’s future, and the referendum plan is a big part of why he thinks we’re in trouble.

He thinks the fact the BC government is putting transit funding to a vote – instead of just plain funding it – is a telling indicator of where their priorities lie, valuing car-oriented development that supports the oil and gas industry but flies in the face of environmental sustainability. He points to Premier Clark’s announcement in September 2013 of a plan to replace the George Massey tunnel with a bridge with added lanes for cars. The price tag for the project will likely be in the billions, similar to the $3.3 billion Port Mann bridge replacement. Both projects were put forward by the province without requiring a referendum – as such ballot measures are rare in Canada – so transit proponents say it’s unfair that rapid transit projects can’t also be legislated so easily.

“Why is it just transit that can’t be built without a referendum?” Price asks. “Why one and not the other?”

To Price, a government that pussyfoots around funding transit while spending billions on highways is a government that’s paving the way to an unsustainable future, where in the place of Vancouver’s lofty “Greenest City” goals, we’ll have sprawling suburbia made for oil and gas fat cats, while waving goodbye to our health, and the health of our environment.

He’s worried the referendum is doomed to fail because there just isn’t time to get a proper campaign together, and because local politicians have been dragging their feet instead of taking a firm stance.

There is one glimmer of hope, though; in February, the BC Liberals conceded that the referendum could be as late as June 2015, instead of coinciding with the 2014 municipal elections as the Liberals had originally envisioned. Todd Stone has asked the Metro Vancouver mayors to come up with a question, to appear on the ballot, by June 2014 – a year in advance. That gives regional planners and policy makers more time to prepare their pitch to the electorate, which Price says is a step in the right direction. “But it would be nice to postpone it until it never happens,” he adds with a wink.

He says the region needs more time because no big names have stepped up to the plate to fight for transit’s future. The mayors are against the idea of a referendum, so they’ve been anything but gung-ho about devising a campaign strategy.

“Looking around for leadership on this is the toughest thing. It’s led by kids,” he says, pointing to Pachal and his colleagues at GetOnBoard BC, a student-led coalition that’s trying to position itself as the ‘yes’ vote campaign team.

“This is the future of the region at stake, and you’re expecting young people, who have other priorities in their lives, to be running this campaign? That just suggests a total lack of seriousness,” says Price, criticizing both municipal and provincial politicians.

He says the stakes are the highest they’ve been in the region since protesters in the 1970s fought to keep Vancouver freeway-free. He thinks a ‘no’ vote would stall transit development for decades, which could kill the city’s “green” image – and its economy. “In terms of jobs and economic development, the most important pipeline to be built in the province will be the one containing the Broadway subway,” he wrote in a blog post in February, saying a transit plan could boost the economy more than controversial oil and gas developments.

Price is adamant the premier should take charge of stirring up support for transit funding.

“We can’t let the province off the hook for something they created. They put us in this position,” he says.

As critical as he is of the lack of leadership from politicians in the region, he says he’s glad young transit advocates are trying to take the helm. He applauds them for their efforts, but still doubts they can actually achieve their goals.

“It’s adorable,” says Price with a smile. Although he adds he is “very impressed” with Pachal’s plan, saying that he and Hillsdon – “just a few years past teenagers” – are the only ones who have come up with something well thought through.

TransLink’s image problem

Price thinks that despite the best efforts of campaigners, the electorate will vote against funding transit improvements because of TransLink’s “image problem.” The region’s transit authority is far from popular, and stories about perceived mismanagement and overspending are regular fixtures in the local news.

The timing of the referendum could make it even worse, as a new fare payment system is getting them into hot water. Throughout 2014, TransLink is rolling out its new Compass Card system. Soon, most transit users will be loading up a card with fares, scanning the card when they board a bus or train, and tapping out when they get off. But before it was even launched, people were already complaining about the prospect of buying a card, and worrying about the program’s potential pitfalls.

“Compass will make it impossible to win public support. It’s new technology, it’s a change in behaviour,” says Price, adding that he doesn’t think the Compass program is poorly designed, but that big changes never happen without a hitch.

“This is going to be a nightmare,” says Price.

He says that’s largely because of a few loud voices criticizing TransLink – or perhaps only one especially loud voice. That voice belongs to Jordan Bateman, BC director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, a non-profit taxpayer watchdog group with a penchant for attacking TransLink. Bateman is very successful at discrediting TransLink and getting media attention.

“Everybody knows if this is a poll on TransLink, it’s dead,” says Price of the referendum.

And according to Bateman, that’s exactly what it should be.

“TransLink needs to stand on its record of how it serves the public, on its waste issues, on its mismanagement issues, and the public will decide,” says Bateman.

He fully supports the referendum as a way of keeping political power in the hands of the public. “Anytime you try to take more tax money it’s good to engage the people in that discussion,” he says. He thinks a ‘no’ vote could teach TransLink to make do with less.

“The leaner you can force TransLink to run, the better, and the better the value for the taxpayers,” he says.

He doesn’t think TransLink needs more money to accommodate a growing population. He says that as the region grows in population, so will its tax base.

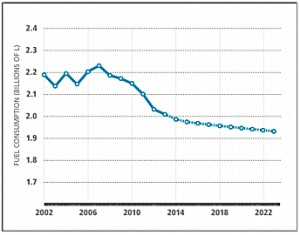

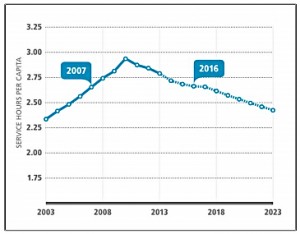

That’s certainly not how TransLink sees it. They see a future of depleted coffers if nothing changes soon. The transportation authority’s 2014 financial plan forecasts a decline in revenue from the gas tax, after a decade and a half of stagnation. People haven’t been driving as much as they used to, and when they do, their cars are increasingly fuel-efficient. Despite a growing population and some gas tax hikes, commuters just don’t need as much gas anymore. The catch-22 is that if transit improvements succeed at getting people out of their cars and onto buses and trains, then gas tax revenue will decline even more. TransLink executives have said that by 2020, if they don’t get any new revenue sources, the service they can provide will be down to 2004 standards – and will only get worse after that.

| Metro Vancouver fuel consumption | Transit service hours per capita |

|---|---|

A lot better than sitting in traffic

“When you’re on transit, it’s not dead time – it’s productive time,” says Pachal. He used to drive, but got rid of his car five years ago and hasn’t looked back, despite spending three hours a day on public transit. He lives in Langley, where it’s taken for granted that everyone drives a car.

He doesn’t mind the long hours he spends on the bus and the SkyTrain. “Whether I’m blogging or reading or even playing a video game on the bus, it’s a lot better than sitting in traffic,” he says, adding that it’s more relaxing than driving. “The times I have driven to work, I usually would arrive pretty stressed,” he says.

Pachal traces his interest in urban planning a few years back to a trip to Portland’s world-famous Powell’s bookstore, which is large enough to have an entire section on urban planning. He was fascinated.

“I was thinking, oh my goodness, there’s so much we should be doing back in Vancouver! And then they announced the Port Mann project. I thought, wait a minute, that doesn’t sound right. That’s not the direction of a livable region. This seems more like Los Angeles or Houston or something,” he explains. The new 10-lane Port Mann bridge was called the widest bridge in the world when it opened in 2012, and had been facing widespread opposition from urbanists like Pachal for promoting car reliance and urban sprawl.

Pachal says he figured naïvely that if policy makers had the right information about the environmental, social and health implications of a car-centric city, they wouldn’t make the choice to build a 10-lane bridge. He was wrong. He knew he had to get involved and make his own arguments for sustainable planning.

He has now been blogging about transportation for more than five years and has helped found a couple groups advocating for better rail and cycling infrastructure south of the Fraser. In 2012, he teamed up with fellow south-of-the-Fraser urbanist and blogger Paul Hillsdon to start working on their Leap Ahead plan. Hillsdon has since taken a job in Saskatchewan so he could actually get paid for the tireless research he does. Together they spent countless hours poring over data about transit improvements that had already been proposed, and compiled as many bits and pieces as they could find to figure out how to fund what’s needed, and how to sell it to the public.

“We wanted to shift the conversation away from ‘We want transit, but is TransLink good or bad,’ and instead say, ‘Here’s a way we can actually fund it,” says Pachal.

He’s now working with GetOnBoard BC as their research coordinator. The advocacy group was founded in 2012 by a group of UBC students; the nine people currently in charge are mostly students and recent graduates, making Pachal, at 30, one of the older members of their team. Despite their lack of experience and political clout, they’re trying to take the lead on advocating for transit in the upcoming referendum. But getting the campaign started is difficult when they don’t even know yet what the question will be. They’re trying to be positive about transit, which is also difficult when “TransLink” is apparently seen as a dirty word.

“For the most part, people are very supportive of transit,” says Pachal, “but many people seem to think TransLink itself is not a well-run organization.”

Pachal agrees with Price that TransLink’s image could be a big problem for the referendum, and he laments how many people see the transit authority as wasteful. He vehemently disagrees that TransLink deserves any of the blame, and has written in his blog about how independent audits have judged TransLink to be well-run and efficient.

Pachal recalls a recent comedy show he saw which involved a scene taking place on a SkyTrain platform. When the train arrived, instead of a bell chime when the doors opened, it said “I’m sorry” – from an audience prompt. One of the actors quickly joked, “It’s sorry because it’s a Canadian train – but it doesn’t really mean it because it’s TransLink.” The mere mention of TransLink drew boos from the crowd, Pachal says.

“I was sitting there thinking, wow, that’s a lot of animosity towards an organization. I could feel the hate for TransLink,” Pachal says. “I wonder why that’s the case.”

Transportation’s a regional issue – until the province meddles

Transit governance in Metro Vancouver has a long history of being criticized and messed with at regular intervals. After decades of changes, TransLink was created in 1999 to manage regional transportation, ending BC Transit’s regional stake. Initially, its board of directors consisted of local mayors and some of the regional district’s directors. In 2007, the Liberal-led provincial government changed TransLink’s structure, in a move that is still widely criticized. The mayors retained the power to approve long-range plans, while a non-political TransLink board, appointed by the mayors, was put in charge of the bulk of transportation governance. It’s the un-elected nature of the board that sparks accusation of TransLink being unaccountable.

Pachal speculates that disagreements on priorities provoked the Liberals to take power away from the regional mayors. “It was when the province was pushing for the Canada Line, and the mayors said, well, actually our priority is the northeast corridor,” says Pachal. “And I think that left a sour taste in the mouths of the provincial legislators. So they said well, you can’t decide anything, but you still get to pay for it – and no one likes that. So that created the conflict we’re in today.”

That conflict is often a disagreement over who really does have the power to plan the regional transportation vision. Pachal also brought up the Port Mann and George Massey bridge projects, which the province pushed forward, even though highway expansions weren’t what the mayors or the TransLink board had in mind. “The province seems to be saying, ‘Transportation is a regional issue – except for when we decide to meddle with it,’” Pachal says.

But the provincial government now seems to be taking heed of the mayors’ concerns. On March 27, Transportation Minister Stone introduced legislation to change TransLink’s governance arrangement once again, this time returning some control to the mayors. The reaction has been generally positive, but mayors and transit buffs just have to wait and see if the change will help voters gain more trust in a more accountable TransLink.

Tips and tricks on winning a referendum

Amidst disagreements between the mayors and the province, the Canadian Taxpayers Federation’s TransLink smear campaign and a general dislike of new taxes, Pachal and his colleagues at GetOnBoard BC have their work cut out for them. But it wouldn’t be the first time people voted in a new tax to fund public transit. The United States have a long history of taxes being put to the ballot, and a 2006 study found that two out of every three local ballot measures proposing new taxes to fund transit were successful over a six-year period.

There’s one example of a successful referendum that everyone seems to mention when they’re trying to be optimistic: Los Angeles’ Measure R. One of the masterminds behind the campaign team that won that referendum, Denny Zane, was invited to Vancouver in October to share tips at an SFU discussion panel on how to persuade voters to hike their own taxes.

Measure R took place in 2008, when Los Angeles County voted in a new half-cent sales tax to fund a $40-billion transit plan. The proposal was supported by 67 per cent of voters in a region criss-crossed with highways, strip malls and vast parking lots stretching out over the horizon. That car-filled horizon is now being transformed into a network of rail lines tracking their way across the metropolis. And it’s already paying off: a recent study from the University of Southern California found that people living near the newest light rail line are already taking transit and walking more, and have reduced their CO2 emissions.

But perhaps it wasn’t so surprising that a transit tax could pass in Los Angeles. Zane’s team capitalized on broader issues that affect everyone in the region, including drivers who haven’t stepped on a bus in decades. Air quality was used as a big selling point: smog in Los Angeles is infamous, so the campaigners said the transit tax could reduce that smog by getting people out of their cars.

Zane’s team also promoted transit as the solution to the region’s crippling gridlock. Los Angeles is commonly called America’s most congested city, so anything to free up roads can pique the interest of commuters who are sick of wasting their time in daily traffic jams. And that’s certainly worth considering for Vancouver’s turn at the transit ballot box; last fall, local headlines proclaimed a new study had called Vancouver the continent’s most congested city, having edged out Los Angeles for the title.

The campaigners in California also addressed financial concerns by convincing voters that improving transit connections was good for the region’s economic development. It doesn’t just cost money, but it generates money and new jobs, they enthused. Zane told the crowd at SFU they shouldn’t complain about the referendum they never asked for, but instead embrace it as a unique opportunity to get their message out there and do something truly special for the region.

Many local advocates are now taking Zane’s words to heart as they hold up L.A. County’s referendum as a shining example of getting drivers to support a pro-transit measure. But it’s only worth talking about if you consider what exactly was on the table. The ballot measure was not just about transit; there was some tax money earmarked for highway projects that may have been more appealing to drivers. It was mostly about transit, certainly, but the extent of the plan probably helped persuade some drivers that there was something in it for them.

Zane said there was another important lesson to be learned from Los Angeles. The plan clearly outlined how transit would improve by setting out detailed plans of where the new tax money would go. Their plan showed new subway, commuter rail, light rail and rapid bus lines stretching across the entire county, which Zane says was key to winning support from voters in every neighbourhood.

But of course, some people in Vancouver already knew that was necessary. Pachal says he and Hillsdon designed their plan with the entire region in mind, so the sales tax they propose (a half-cent increase, just like the one in Los Angeles) would fund not only a subway along Vancouver’s Broadway corridor to UBC, but also three light rail lines in Surrey, a gondola to SFU in Burnaby, and new B-Line express bus routes stretching across 14 different municipalities.

The blame game

“The great thing about referendums is that everyone has exactly the same number of votes. I have one vote, Gordon Price has one vote – we all have one vote,” Bateman says. He thinks the referendum is a great opportunity for everyone, not just transit buffs, to help shape public policy. And he’s hopeful that they’ll say no to more taxes.

“The people pushing the ‘Yes’ side very much fear the public – and rightfully so,” he says. “The public is ticked off.”

Bateman thinks it’s time for government agencies to rein in spending instead of splashing out on expensive new projects. He says Vancouver is entering a period of slow growth, so governments should just accept that there isn’t as much money to throw around as there was before the recession hit. He thinks the public can see that, and that most people want their government to be savvier with their hard-earned cash – and are tired of TransLink’s spending habits.

“This is a TransLink issue. You’re talking about giving huge new tax tools to TransLink, so it’s crazy to think you can divorce that from the record.”

And his message has certainly been heard – countless news articles have quoted him, as the region’s leading expert on criticizing TransLink’s every move. Pachal thinks Bateman has profoundly harmed TransLink’s image, and knows how to work the media, pointing out that Bateman has previously worked both as a journalist and a Langley township councillor before taking the helm of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation in B.C.

“I think their bad reputation is pretty much caused by a misinformation campaign of one,” Pachal says.

“I don’t want to blame the media,” he says carefully, “but sometimes, they just print press releases from the CTF without checking their facts.” And he’s concerned about the effect that has. “If you were to believe Jordan Bateman, you would think that all they do at TransLink is burn money for fuel,” he says.

Pachal’s been adamantly countering their accusations on this blog. And he’s certainly not alone; Daryl Dela Cruz, 18, has been writing about transit since he was in high school.

He’s also from the south of Fraser – Surrey to be specific, although he’s since relocated to Burnaby – and says a lot of young transit advocates are. He chalks it up to the longer transit commutes in that area. “It’s maybe not the best transit experience out there, so a lot of people want to make it better, and just make it work,” he says.

“I think the thing about young people is that we want to orient ourselves around transit; by getting into it at the very beginning, we’re discovering how it can make us productive citizens,” Dela Cruz says.

Dela Cruz was still in high school when he founded a website called Better Surrey Rapid Transit, where he and a pair of fellow advocates are campaigning for SkyTrain extensions into Surrey. He says we need to be looking beyond the capital costs of such projects, and look at the benefits that fast, reliable transit can yield. “We need to demand the best,” he says, adding that SkyTrain would be much better than light rail without a big increase in cost.

“I’m motivated by the idea that here in Metro Vancouver, we could become a centre for innovation. We’re already on track to become the world’s greenest city, and I think we can use that to set an example for other cities around the world. I like that idea of being an example setter, so I’m working to get us there. I want us to lead,” he says.

Dela Cruz shares Price and Pachal’s concerns about TransLink’s public image, and is working hard to change it. He recently responded directly to the CTF, after they issued a “Teddy Award” to TransLink for wasting taxpayers’ money – which was picked up by dozens of news outlets. They singled out one recent case of a park and ride lot expansion with a reported price tag of $4.5 million that’s been sitting empty because of a new parking charge. Dela Cruz didn’t dispute that a new parking lot shouldn’t be sitting empty, but after doing some digging into policy documents and older news stories, he discovered that the blame was misplaced. He wrote a long post explaining that it was the province, not TransLink, that planned the lot expansion, and the city of Surrey could also be blamed for allowing commuters to park on neighbouring streets.

That’s not to say he thinks the system’s working perfectly. He agrees that a change in the governance structure could help rebuild faith in local transit management, so he’s hopeful things could improve thanks to the steps the province is taking to modify TransLink.

“I’m pretty sure that will solve a lot of problems, but it won’t reverse the damage. There’s been a lot of damage caused to their image,” he says.

Do something about it

Pachal says he’s growing frustrated with the lack of leadership shown by political leaders in the region.

“What I find the most troubling is that when we released Leap Ahead, I got some calls from mayors thanking me for my work, and saying they think it’s a great plan. But publicly, they didn’t say one thing or the other. There is a vacuum of leadership when it comes to proponents of transit funding, and how to pay for it.”

He said politicians are hesitant to stick their necks out to support public transit, often preferring to remain mum on the issue or speak only in general terms without making any big commitments that might put their political careers at risk.

Pachal is tired of what he sees as political inertia when it comes to designing sustainable communities in his part of the region. He says some local politicians are stuck in the past, and haven’t got past the outdated notion that everyone drives, lives in a single-family home, drives their SUV to the mall and comes home to a spouse, two kids and a dog.

He’s had enough of blogging from the sidelines, so he’s decided to go one step further in his dogged way of taking matters into his own hands: he’s gearing up to run for Langley City council in November’s municipal election. His days of blogging from the sidelines could be coming to a close if he can make his voice heard on council.

“If you see something you’d like to change, then you shouldn’t just complain,” he says. “Go do something about it.”

Published April 2014. For more background on this subject, see the literature review, completed as a part of this thesis project.