A Global Problem in Perspective: Urban Population

Abstract

At a global scale, urban population has dramatically increased for several decades, and has accounted for more than half of the total global population. Urban population growth characterizes the global population trends, highlights the dynamic and ongoing interplay between social and environmental systems, and demonstrates implications for a sustainable future for both humanity and the environment. This paper attempts to presents an overview of the issue of urban population growth, to explain the importance of studying it and to discuss it in light of the DPSIR model. The causes and consequences of urban population growth are necessary to be understood and evaluated towards achieving a sustainable urban growth.

Introduction

Like the notions of modernization in the 1960s and globalization in the 1980s and 1990s, urbanization is a natural by-product of global scale industrialization, modernization and economic development. It is important to acknowledge that urban growth vary differently by countries and regions. Not all cities and towns can achieve growth. In fact, urban growth and decay are two sides of the same coin of urban change. Sustainable planning for urban growth is to be combined with appropriate planning for decline. Reasons for shrinking cities include economic recession, migration, local conflicts and tensions, poor environmental conditions, loss of political importance, administrative changes to cities, etc.

Urban population increase is the one of the main reasons for urban growth, while in return, urban growth promotes more urban population, forming a benign cycle. In this paper, we only look at urban population growth, partly because urban decay and population decline in specific regions or cities are relatively insignificant compared to urban growth at a global scale, and also because urban change is so highly interlinked with urban population in different regions that if we take into account all of them, it will require much larger datasets and introduce much more complexity that might not be handled properly.

A Global Problem in Perspective

To give the reader a sense of how the issue of urban population evolves, and to what extent, I will start by introducing its long history and widespread influence. Several urban intellectuals had predicted the appearance of an urban transition on a world scale since the twentieth century, and during the following decades, this prediction was more and more frequently repeated in journalistic and academic reports (Brenner & Schmid, 2014; ) Today, urban population is discussed everywhere, by some of the most influential urbanists of our time, international organizations such as UN and the World Bank, governmental and non-governmental agencies, scholarly and non-scholarly documents, and various media sites. The urban age thesis, one widely recited claim that “we now live in an ‘urban age,’ because for the first time in human history more than half the world’s population today purportedly lives within cities,” is used as a reference point by anyone concerned with the global urban conditions (Brenner & Schmid, 2014, p. 731).

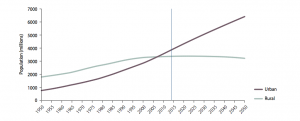

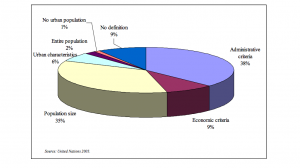

However, difficulties inherent in defining and measuring the size of urban population make it a challenging and debatable task. Some of the most commonly cited statistical population data sources and the estimates of current and future trends based on those data have been criticized by several scholars(Brenner & Schemid, 2014; Bocquire, 2005; Bloom, Canning, Fink, Khanna & Salyer, 2007). As summarized in figure 1(based on the latest release of the UN’s world Urbanization Prospects), the fraction of urban population has been growing rapidly. Postwar attempts to measure the global urban population were hindered by methodological and theoretical limitations in early twenty-first century academic, political and ideological discourses, where the first fundamental problem analysts encountered was how to determine the spatial boundaries of given areas, an issue that has been confronted and explored through various strategies and yet remained inadequately resolved (Brenner & Schemid, 2014). In other words, how many inhabitants were required to be classified as urban was undefined.

As urban issues receive more attention, there rises the need for an global trend instrument that complies database in tremendous scope and optimal quality. Today, those obstacles were overcome by more systematic definitions and complicated projection models. However, the UN projected World Urbanization Prospects are still considered biased and lacking accuracy in predicting the future urban population trends, and to be more specific, they overestimated the population of different countries to varying extents (Bocquire, 2005). The hot debate over an appropriate projection model reveals the problems of insufficient available dataset, the significance of urban projections for demographers and geographers, and the implications for scientists and policy makers. The discussion of urban population is thus enriched and environmental policies are gradually brought to the table.

Figure 1. Urban Population Share, 1950-2030

DPSIR Framework: Drivers

DPSIR model has been widely used as an integrated approach for analyzing causal links of environmental issues, starting with “driving forces” through “pressures” to “states” and “impacts” on ecosystems, human health and functions, eventually leading to political “responses” (Kristensen, 2004). For the issue of urban population boom, the DPSIR framework is helpful in linking key elements and describing the causal relationship between the causes and consequences, providing us with insights into the dynamics of this environmental problem.

After reviewing all the key determents, I summarize three main categories of driving forces: (1) natural population growth; (2) migration into urban areas; (3) urban growth. The objective of the following sections is to explain these three main drivers.

Rapid growth of urban areas is the result of two population growth components: (1) natural population growth, which results from more births over deaths; (2) migration, which results from the movement of people from rural to urban areas. Evidence shows that population growth itself will naturally promote higher levels of urban population shares in the long run, because increases in the size of a given settlement either lead directly to increase in urban population or, for smaller settlements, lead to their reclassification from rural to urban settlements as populations exceed predetermined thresholds (Bloom, Canning, Fink, Khanna & Salyer, 2007, p.2). The natural and mechanical increase in urban population depends on original population and city size, living environment, industrial and economic agglomeration and location.

Global population growth is one of the principal drivers of urban population growth in most countries, but in the absence of population growth, migration becomes the key determinant of overall urban population growth, estimated to contribute between 40 an 50 percentage of total urban population growth on average (Bloom, Canning, Fink, Khanna & Salyer, 2007, p.12). Migration within the country results from push factors(i.e. original places are perceived by migrants as detrimental to their well-being) and pull factors(i.e. new places are attractive to migrants). Examples of push factors include high unemployment, detrimental living conditions, low access to information and opportunities, low income, etc; examples of pull factors include better living conditions, work or school opportunities, a greater variety of entertainment, better quality of education, more access to information and facilities, higher salaries, more services, better lifestyle, more diverse social communities for social interaction, etc. To be noticed, urban population growth is heightened when a pre-industrial society is transitioning to an industrial one. Industrialized countries have relatively lower urban population growth, and a large portion of their population live in urban areas already.

To understand the spatial and temporal dynamics of urbanization processes, the factors that drive urban development must be identified and analyzed, especially the ones that can be used for future prediction and environmental impacts management. The idiosyncratic nature of urban areas suggests a large number of factors that interacts with industrial and economic growth in determining urban expansion and population growth. Since urbanization plays a critical role in a country’s development, especially for developing countries, they build a vast network of new cities and thus increase urban population to fuel their economic, social, industrial and cultural goals. According to Kristensen (2004), a driving force is a need, and in this case, it is the result of different mixed of economic, social, industrial and also individual factors. Scholars have identified a large number of biophysical and socioeconomic drivers that results in urban growth, including administrative and political changes in city status, land use policies, economic policies and incentives, local and destination institutions, government policies to develop small towns, geographic concentration of investments, international capital flows, the informal economy, generalized transport costs, foreign direct investment in industrial employment, relative rates of productivity generated by land associated with agricultural and urban uses (Zhang, Wallace, Deng & Seto, 2014; Seto, 2011; Güneralp & Seto, 2008; Seto & Kaufman, 2003).

DPSIR: Pressures, States and Impacts

While driving forces lead to human activities, these human interventions exert pressures on the environment, which includes use of land and resources, external inputs(e.g. fertilizers, chemicals, irrigation), production of waster, production of noise, direct and indirect emissions of pollutants and waste, and modification of organisms(Seto & Kaufman, 2003; Güneralp & Seto, 2008). The quality of various environmental compartments are thus affected, which is a result of those pressures. The state of the environment is the combination of the physical, chemical and biological conditions of the ecosystem. For example, air quality is affected due to more vehicular uses; water quality is affected due to water pollution from factories; soil quality is affected due to farming chemicals; biodiversity is affected due to climate change; human being’s health is affected due to unhealthy food production resulting from industrialized agriculture. And the list goes on and on.

In addition to the many positive associations of urbanization such as economic growth, accessibility to services, and more diverse culture development, there are also negative environmental impacts to be considered. Researchers have identified several environmental indicators: land use, air quality, demand for water and energy, threat to protected areas (housing related),habitat loss, species extinction, elevated temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, energy consumption, and land, water, and air pollution (Güneralp & Seto, 2008; Seto, Fragkias, Güneralp & Reilly, 2011; Bloom, Canning, Fink, Khanna & Salyer, 2007).

Furthermore, large scale and rapidly growing slum populations are formed around many major cities. In the developing world, slums are among the most graphic and vivid presentations of social disparity and poverty, characterized by detrimental living conditions and lack of most basic services.

The conversion of Earth’s land surface to urban uses is one of the most irreversible and human-dominated impacts on the global biosphere. Land conversion into urban uses causes loss of productive farm land, fragments habitats, modifies hydrologic systems, increases energy demand, affects the local climate, and threatens biodiversity. In some rapidly urbanized areas, agriculture is not sustainably planned, generating pressure on land resources. As demand for water and electricity rises, the city becomes more vulnerable to shortages of those supplies.

DPSIR: Responses

We have identified a long list of environmental impacts on the functioning of ecosystems, our human health, and on the economic and social performance of the society. Future trends depend on how we adapt to, or mitigate those undesired impacts through policy measures, technologies, and other means. As the urban population continues to rocket, more sustainable policies are needed to ensure that the benefits of urban growth are shared sustainably, and that urban growth follows a more balanced distribution. For example, the government can promote public transportation to reduce private car uses; municipalities can offer opportunities to expand access to services in an economically efficient manner.

Given the complicated interplay between urban expansion and urban population growth, a complete evaluation of the issue of urban population growth is rather difficult. From a research perspective, more detailed, extensive, accurate, timely and better quality datasets on global urban population are needed to determine priorities and directions for policy making, because they were critical for assessing current and future trends. As much as urbanization can be a natural outcome of modernization, industrialization and economic development, it can become a major environmental and social problem if effective institutional and policy frameworks are absent. Therefore, from a policy perspective, government should be more responsible when integrating sustainable considerations into the economic and industrial development.

Reference

Brenner, N., & Schmid, C. (2014). The ‘Urban Age’ in Question. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), 731-755.

Kristensen, P., (2004). The DPSIR Framework. Retrieved from http://wwz.ifremer.fr/dce/content/download/69291/913220/file/DPSIR.pdf

European Environment Agency. (2008). [Graph illustration the DPSIR framework]. Retrieved from http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/92-9167-059-6-sum/page002.html

Bocquire, P. (2005). World Urbanization Prospects: An Alternative to the UN Model of Projection Compatible with the Mobility Transition Theory. Demographic Research 12(9): 197-236. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2005.12.9

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Günther, F., Khanna, T., & Salyer, P. (2010). Urban Settlement: Data, Measures, and Trends. In Beall, J., Guha-Khasnobis, B. & Kanbur, R. (Ed.), Urbanization and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (chapter 2). Oxford Scholarship Online. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199590148.001.0001

Zhang, Q., Wallace, J., Deng, X., & Seto K. C. (2014). Central Versus Local States: Which Matters More in Affecting China’s Urban Growth? Land Use Policy, 38, 487-496.

Seto, K. C. (2011). Exploring the Dynamics of Migration to Mega-delta Cities in Asia and Africa: Contemporary Drivers and Future Scenarios. Global Environmental Change, 21(S1), S94-S107.

Seto, K.C. & Kaufman, R. K. (2003). Modeling the drivers of urban land use change in the Pearl River Delta, China: Integrating remote sensing with socioeconomic data. Land Economics. 79(1):106-121.

Güneralp, B & Seto, K. C. (2008). Environmental impacts of urban growth from an integrated dynamic perspective: A case study of Shenzhen, South China. Global Environmental Change 18 (4), 720-735.

Seto, K.C., Fragkias, M., Güneralp, B., & Reilly, M.K. (2011). A Meta-Analysis of Global Urban Land Expansion. PLOS ONE 6(8): e237-277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023777

figue 1.

figure 2.

figure 3.

figure. 4

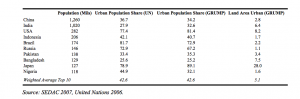

figure. 5

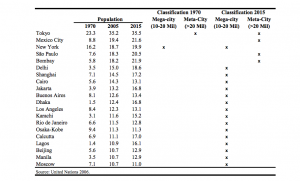

table 1.

table 2.

table 3.