Conservation has entered the spotlight in recent years, but there is one resource shortage no amount of recycling can help: human organs. Every day 2o people die waiting for an organ transplant and this problem is only getting worse. From 1991 to 2015, the number of people on the transplant list in the US has risen by nearly 100, 000, while the number of donors has risen by less than 10, 000. This problem is exasperated as only 3 out of every 1000 deaths leave organs viable for transplant. Luckily Biologist Luhan Yang may have a solution with an unlikely face.

Source: Google

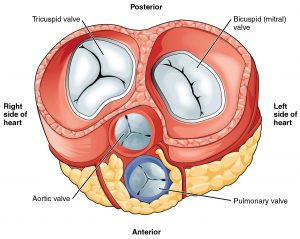

Yang literally hopes to bioengineer pigs into human organ farms. Yes, organ farms. Although it sounds crazy, xenotransplantation, the transplant of animal tissues/organs into people, is not a new concept. Pig and cow heart valves have been transplanted into humans as an alternative to mechanical valves for almost 50 years. But implanting a functional organ is very different than implanting a simple valve.

Source: Flickr Commons

Pig and cow heart valves are treated with a variety of chemicals to preserve the tissue and prevent it from rejection by the immune system. Since the tissue is only preserved, it is not technically alive, which obviously would not work with an organ. To be of any use, an organ must be alive and fully connected to the rest of the body, which understandably presents some major problems.

The first problem is organ rejection. Everyone’s cells have protein “markers” displayed on their surface completely unique to the individual. Your immune system uses these to distinguish between what’s you and what isn’t, so it doesn’t accidentally attack itself. That’s why patients’ blood types AND protein types must match for a transplant to be successful. Even then, the recipient must spend the rest of their life taking anti-rejection medications. Even organs from close family members often don’t match well enough to risk the operation, so transplanting from an entirely different species is undoubtedly more difficult.

Source: Flickr Commons

The second problem is the potential spread of viruses. Pig and human anatomies share certain similarities, which makes them ideal to grow organs. But this means many of their diseases can also infect us, like the H1N1 swine flu outbreak in 2009. Specifically, the type of virus of concern is called an “endogenous retrovirus”. Retroviruses are a special type of virus able to open up an infected host’s DNA, and insert its own before repairing it. This means the virus is literally part of the pig’s genome, and therefore is exceptionally difficult to remove.

Source: Flickr Commons

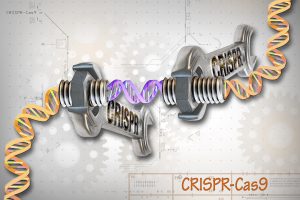

This is where Yang comes in. She hopes to solve these issues by genetically modifying pigs using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. CRISPR is a revolutionary gene editing technique that allows scientists to open organisms’ DNA up at specific locations to add or remove segments. In 2015, Yang’s team made history by successfully developing a method to remove 62 retroviruses from pig cells at once. It was the largest number of modifications ever done to a mammalian genome in one procedure. Then last year, her team produced 15 live piglets without any harmful retroviruses. Their next goal is to take CRISPR even further to produce what they call “Pig 2.0”. They hope to further modify pig’s DNA to make their organs more human-like, solving the problem of organ rejection.

One response to “An Unlikely Hero”