The Greatest Storm on Earth

When thinking about powerful natural events on Earth, one might think of raging tornadoes, or blizzards that can shut down cities, but the power of a hurricane is so immense, that they can release up to 10000 nuclear bombs worth of energy of the course of their lives. The power of these natural storms is so great, they are sometimes even visible to Earth even from other planets in our solar system, take the Great Red Spot of Jupiter for example. On Earth, generally hurricanes start to develop in areas of high humidity and relatively warm surface water temperatures, mixed with faint winds. This is why “hurricane season” is generally in the summer and early fall in the northern hemisphere. Hurricanes are devastating to the terrain and any infrastructure caught in their path, and as such is an important issue for people who live in areas known that are likely for hurricanes to hit. The video below from National Geographic goes over some of the specifics when it comes to how a hurricane is made, for further info on the topic.

Hurricane Decay

Eventually, when hurricanes hit land they will slowly start to decay, as the moisture from warm ocean subsides, the hurricane has nothing fueling it, as hurricanes require moisture and heat to continue on. After being cut off from the ocean, the decrease in moisture level also contributes to an simultaneous decrease in the hurricanes intensity.

In the scientific literature, there are already studies looking at how climate change affects hurricanes, and particularly how climate change affects the intensification of some tropical cyclones, but until recently, the question of how the intensity decay was being affected by climate change remained unanswered.

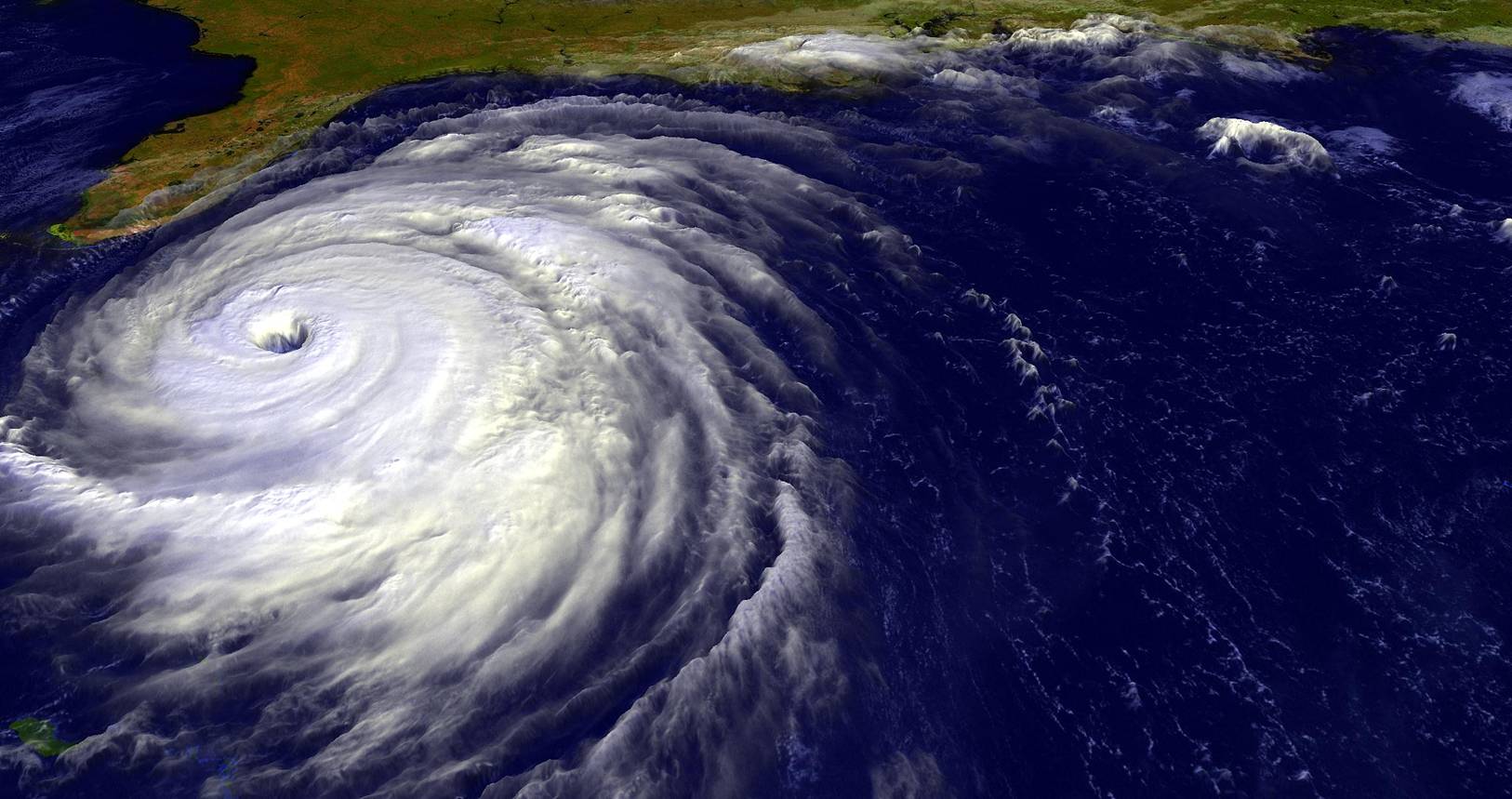

A hurricane at the start of hurricane season / Taken from Flickr user militarymark2007

The Findings

Recently, researchers Lin Li and Pinaki Chakraborty of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology have determined through an analysis of historical climate data, alongside computer simulations, that climate change is contributing to the slower decay of hurricanes after landfall. By checking through the hurricane intensity data gathered over the last 50 years in the North Atlantic, they found that “hurricane decay has slowed… in direct proportion to a… rise in the sea surface temperature”. Looking back to the late 1960’s, an average hurricane then would lose around three quarters of it’s intensity a day after it made landfall, whereas an average hurricane now would only lose around half of it’s intensity a day after making landfall. By using computer simulations, they determined that the higher sea surface temperatures are causing the slower decay rate, as the moisture level is now also higher, alongside the amount of heat to fuel the hurricanes ‘engine’, leading to a longer and stronger hurricane after landfall.

Looking Ahead

As we look forward, strategies to mitigate climate change and reduce global warming might become top priorities in a world with an ever increasing climate, and unfortunately now, with even stronger hurricanes.

Hurricane as seen from the ISS by Astronaut Ed Lu. By Image courtesy of Mike Trenchard, Earth Sciences & Image Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center. – http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/NaturalHazards/view.php?id=12140, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=625449

– Mehdi Mesbahnejad