Resist. Rinse. Repeat

[First of: here are some sweet tunes I found while researching Indigenous Futurisms. I’m sure you’ve heard this mixtape before, but here it is, one more time, in all its cybernetic glory.]

A few weeks ago, when I first started thinking about this blog, I realized I found the task particularly difficult. How can we sensibly write about indigenous futurisms? My first thoughts ran along the lines of: haven’t we changed indigenous people’s lives enough already? We are even going to imagine their future? My second line of thought started by asking myself: what future, then, belongs to me? What does a Latinx future look like? Does it intersect with an Indigenous one? A Black one? Does it even exist? How can I use Indigenous Futurist theory to both act as an ally to Indigenous people but also to work in an intersectional fashion with other PoC issues? More than anything, this blog post comes as a response to the state of mind and further action that this prompt got from me.

At the beginning of this writing process, I realized that if I stop and try to analyze the times we are currently surviving in, I find it almost insensible to think about the future. A normal day in my life, since the USA presidential election occurred, and every other terrible decision that the world has taken lately -be that Colombia voting No to peace (which doesn’t seem to get discussed too much on this side of the continent but that very deeply affects the future of millions of Latinx), Brexit, Spain and Rajoy, you name it- my mood swings from incredibly sad and full of despair, to anger, hopelessness and powerlessness, with some hints of fully unadulterated happiness, received every time I hear one of my PoC friends do something to tear the oppressive system that keeps trying to suffocate us more and more everyday.

When I first saw the description and follow up emails for this blog post I had a few thoughts running through my mind. At first, I found myself being incapable of writing a positivistic post in which I would talk about how “everything will be all right in the end; If it’s not all right then it’s not yet the end” because this feels like the end and nothing is alright. I found myself tired of listening to my professors telling me that it will all be fine; how it needs to get really bad before it gets better. Thing is, I’m uncertain, and I think that those feelings need to be not only validated but heard. Ultimately, and with my friends’ help, I sprung to action and turned to art. Art as resistance, art as medicine, art as hope, art as community. How does art imagine Indigenous, Black, Latinx and more PoC futures? How do artists explore and create PoC futures through art? First let’s think about what Indigenous Futurism is:

The first time I heard about futurism in an “academic” context, it was while talking about Italian Futurism in 1909 with their infamous manifesto. This movement came originally from an idea of a new Italian nationalistic identity, with its members attempting to bring about social transformations through art. Being part of a series of art movements that Peter Bürger called the “historical avant-garde”, futurism, along with others, was characterized for being highly ideological and combative. They were not just against the ruling institutions; they were against society’s core values. They framed their relationship with society as a battle, applying ideas of war to art and using language to violently describe society. War, as they put it, was the “sole cleanser of the world”. They admired art as a catalyst of change, a way to appreciate a new speed of life, combating the idea of the past, trying to completely disengage from it.

F. T. Marinetti. “Manifeste du futurisme” [Manifesto of Futurism]. February 20, 1909, Le Figaro.

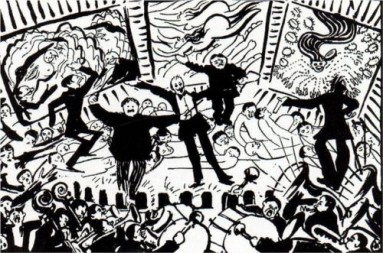

Umberto Boccioni, A Futurist Evening in Milan, 1911

Although Italian Futurism and Indigenous Futurism share no similarities other than the idea of building a future different from the present we are currently experiencing, I think it’s important to talk about the ways in which both movements used and use art as the tool to generate change. The ultimate goal of Marinetti’s Futurism was to transform art into life. To do this, they wanted to enter the public arena in a “direct and combative manner”. To achieve this, they would hold public Futurist evenings in which they held performances in front of audiences, where they would talk about politics and propaganda in very inflammatory ways, hoping to instigate a sense of revolt in their audiences. They ultimately stepped outside of the confines of the art studio to become revolutionary practitioners. In that sense, the only similary that I believe these two futurisms share is the infiltration of art as protest, as possibility, into broader discourses and mediums. Indigenous and other types of PoC Futurism is present in music, literature, visual arts, etc. spreading their ideas as wide and loud as possible. The message is clear: Indigenous and other PoC bodies will be a part of the future. In fact, we are the future.

Janelle Monae and Erykah Badu, Q.U.E.E.N. (Queer, Untouchables, Emigrants, Excommunicated, and Negroid.), 2013.

The term Indigenous futurism was coined by by Anishinaabe Science Fiction critic Grace Dillon to bring together ideas about Critical Indigenous studies in Science Fiction, in 2003. This genre has historically used indigenous and other PoC bodies as “foils” to stories of white explorers that seek to conquer new worlds, in their desire to continue colonizing, ad infinitum. The idea, as author Nalo Hopkinson so beautifully puts it, is that when people of color engage with Science Fiction, they “take the meme of colonizing the natives and, from the experience of the colonizee, critique it, pervert it, fuck with it, with irony, with anger, with humor and also, with love and respect for the genre of science fiction that makes it possible to think about new ways of doing things.” There is a pleasure felt by PoCs, Lou Catherine Cornum affirms, when these desires of colonization are inverted, questioning who the explorer and the “exploree” are.

Additionally, as PoCs imagine a future that includes an intersection between traditional knowledge and technological invention and development, it is sometimes argued that these ideas make settlers uncomfortable, as indigenous people are always imagined to exist in the past tense, unable to “reach” a future marked by colonial western technology. Nevertheless, the notion of an indigenous futurism does not begin with an idea of a future similar to the present we live in now, that has become more and more inaccessible for our existence, our happiness, and our hope. An Indigenous futurism is the one in which we imagine and seek for completely new worlds, worlds in which brown bodies are not brutally murdered, silenced, taken advantage of, studied… [continue this list ad nauseam].

Imagining the possibility of being in other worlds is enacted differently if thought from an indigenous futurist perspective. After all, and as Lou Catherine Cornum argues, “not all encounters with the other must end in conquest, genocide, or violence”. Not only does this idea of exploration not stem from a necessity to claim space (or “discover” already existing spaces), but it is also not about assuming that every other possible world is “ours” to claim, terra nullius waiting for someone to claim ownership over.

Additionally, if thinking specifically about cyberspace and the encounter with its cyberland, it is important that we recognize both the possibilities and hindrances of putting our work in a space like this. As argued by Skawennati Tricia Fragnito and Jason Lewis in Aboriginal Territories in Cyber Space, cyberspace gives us the opportunity to “assert control over how we represent ourselves to each other and to non-Aboriginals”[1]. Seeing this possibilities and remembering the history of the medium is of paramount importance, nevertheless. Skawennati and Lewis remind us that the foundations of cyberspace were built with the specific logic of keeping communication channels open for military corps. “The ghosts of these designers, builders, and prime users continue to haunt the blank spaces”[2].

With these ideas in mind, I would like to speak to the two responses this prompt elicited in me. First off, this year I had the immense pleasure of taking a Performance Art seminar with a group of 11 unbelievably talented artists and professors, including Catherine Soussloff and Guadalupe Martínez. In addition, towards the end of this term, I was lucky enough to see all of my courses intersect in very transformative and important ways. As I thought about my final performance for this seminar, I began by doing what I do every night. I talked to my roommate Ghada. Ghada and I have a tradition: every night, once we both get home, we will go to one of our rooms and we will talk about our days. We will discuss the good, the bad, the sad and funny things that happened in it. We will exchange stories about the micro-aggressions we have to deal with every day, from people coming up to me and touching my hair without my consent to people commenting on how “ethnic” I am. Thus, every night, we hold space for each other; We listen, we carry each other’s burdens. As we do, the day I first read this assignment’s description, right after the elections result, I was full of anger. I had realized I did not know if I would exist in the future. When our entire existence is being jeopardized, imagining the future made me feel sick. Luckily for me, she pushed me, as she does every day, to believe in the possibility and existence of our futures, of utopia. Out of those talks came my final performance, which you can see here:

A transcription of Resist. Rinse. Repeat.:

To the woman that asked me where I had “gotten” my hair. As if she could it buy off me.

To her: When I say “I’m sorry, I don’t understand you question”, I am asking you to see your desire to purchase me materialize in front of us. That desire to consume me. To own me.

A usted le digo: mi identidad no está a la venta.

To every person that has ever called my huipiles festive, while examining my dress, up and down, satisfied knowing they have named the crime of wearing so many colors at the same time.

To you: My dress is protesta. It is history. It is labor. It is the hands of women that have sown their essence into every ícono in every dress I have ever had the honor of wearing.

A ustedes les digo: mi identidad resiste tu historia.

To the man that told my friend her culture was ridiculous. Why don’t Japanese people hug? He asks. Your culture makes no sense, he says.

To her: I will be there for you, to witness, to resist, to stand with you.

You are loved and you are love.

A ustedes les digo: mi identidad no depende de su validación.

To the indigenous artist that reminded me that the color of our skin is a threat to some. For reminding me that our existence is resistance. For reminding me that we are not at peace.

To them I ask: what does this skin do to you that makes you hate us?

A ustedes les digo: mi identidad perdona pero nunca olvida.

To my friend: for listening, for sharing pain, for sharing love, for sharing sadness, for holding space.

To you: I promise to stay soft. I promise to believe in utopia. I promise to imagine our futures, alive. I promise to say your name as many times as I can until the sound you hear coming from my mouth reminds you of home.

Finally, the second (Re)action that this assignment prompted me to do can be read here. What I take away from this class is the urge to organize myself and my community to build spaces that entertain the thought of our existence in the future. A future in which there is space for collaborative action, interdisciplinary studies, and creative economies. The tools that have been given to us in university and through our own lived experiences must be applied outside the walls of the institution. We must believe in the possibility of tomorrow. We must make the possibility of tomorrow a reality.

[1] http://gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures/

[1] Lewis, Jason and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito, “Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace”, in Cultural Survival, 29.2 © 2005 Cultural Survival.

[2] Lewis, Jason and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito, “Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace”.

You do an excellent job framing this post from your own positionality and you bring Cornum (one of my favourite IF scholars) into the conversation. The performance piece is also quite lovely. Thank you for sharing it here.

I would have like a bit more of an in-depth reading of Timetraveller, however. How do you see that piece fitting within the larger discourse you present here?