BY Nicholas Choy & Caroline Chiu

Motivation

Generally sulfur dioxide (SO2) causes severe health consequences such as reduced lung function and chronic bronchitis which can lead to mortality; as well as negative economic impacts such as deforestation and acidification of water bodies and soils (SILAQ, 1998). Environmentally, SO2 contributes to acid rain.

Poland is a main contributor of air pollution in Europe (Kiuila, 1999) and its SO2 emissions level per GDP are two to eight times higher than average OECD levels (Blackman and Harrington, 1999). Therefore, Poland implemented environmental charges following the Polluters Pay Principle, with the following three objectives (Blackman and Harrington, 1999):

1) To charge a rate that is high enough to encourage polluters to innovate rather than just paying the charge

2) To relate the rate to the marginal damages caused by emissions

3) To generate national revenue for investment in environmental initiatives

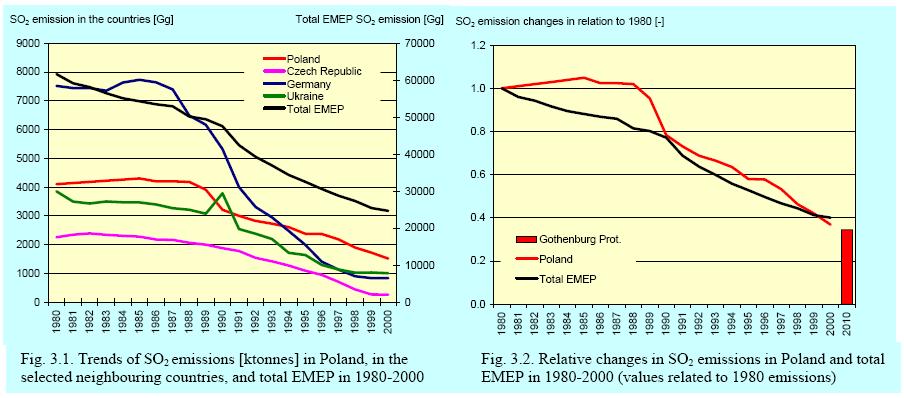

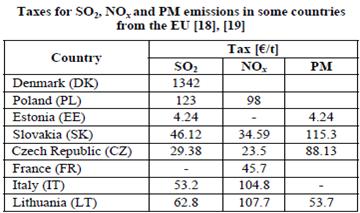

These objectives are created in conjunction to fulfill Poland’s short, medium and long term environmental goals in the National Environmental Policy. Poland refused to sign the 1985 Sulfur Protocol because their economy was dependent on mining and metallurgy at the time (Harris, 2007). But seeking membership in the EU prompted Poland to meet international standards. Economic hardship in the late 1980s reduced output, and subsequently SO2 emissions, which initially made meeting reduction targets possible. Currently, Poland’s SO2 emissions fees are one of the highest in the world.

(Paraschiv, Paraschiv and Ion, 2011)

(Paraschiv, Paraschiv and Ion, 2011)

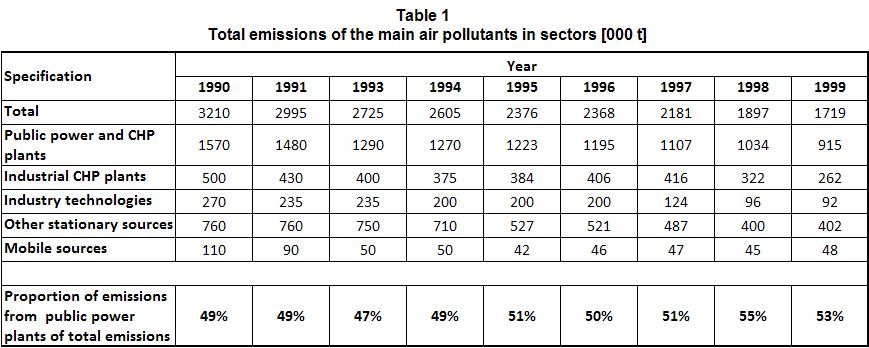

Emissions by sector

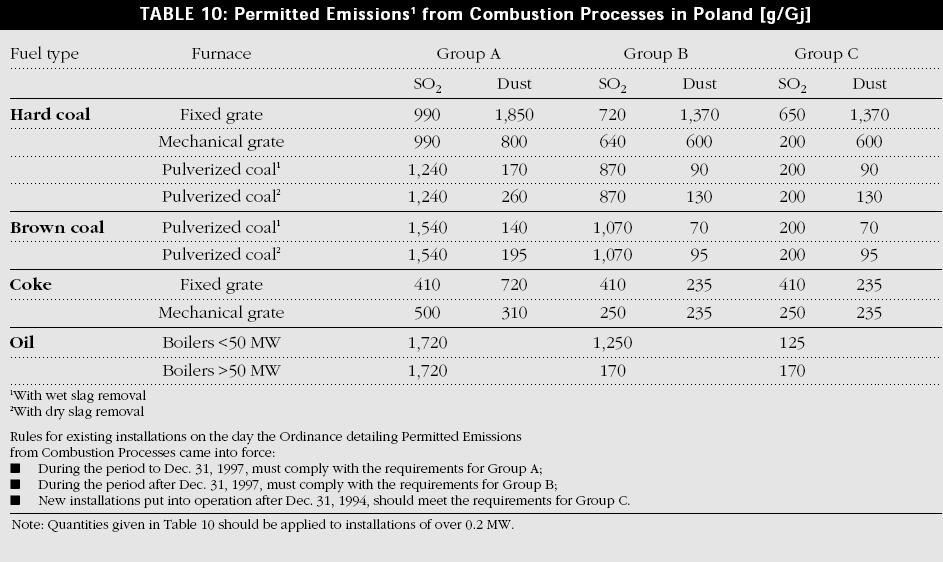

The tables below indicate that power generation and industrial processes are the largest contributors of SO2 (Kudelko and Suwala, 2003).

Timeline

1980 Airborne emissions fee system established (Blackman and Harrington, 1999)

1990 Fees too low– tax rate revamped (no significant reduction until revision)

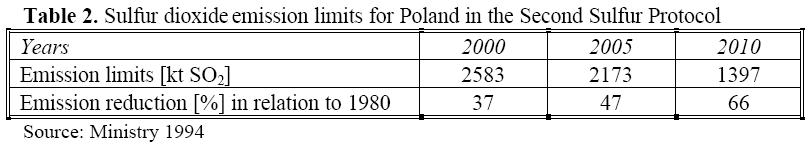

1994 Poland signed the Second Sulfur Protocol (Harris, 2007)

1995 SO2 “normal” fees = USD $83/ton (Blackman and Harrington, 1999)

1996 Agreement between Ministry of Industry and Environment

Protocol – 2 targets: meet 2000 and 2005 limits

Second Sulfur Protocol (SSP) – meet 2010 limit in 2010 (Kudelko and Suwala, 2003)

(Kiuila, 1999)

(Kiuila, 1999)

Compliance cost, especially to power generation sector, was 1750m € to meet 2005 limits, and 6400m € to adjust to the SSP limits. (Kudelko and Suwala, 2003)

2011 SO2 fees = €123/ton (Paraschiv, Paraschiv and Ion, 2011)

Implementation: A hybrid system of permit and fee instruments. Facilities must have permits to emit SO2 and emissions below a specified quantity incur a “normal fee” or tax rate. Those emitting above this standard level pay a penalty fee up to 10 times the normal fee (Blackman and Harrington, 1999); analogous to a two-tier tax rate system.

Distribution of permits: Firms must submit a comprehensive environmental impact analysis that includes detailed information such as production levels, production processes, fuel types, emissions to be discharged, and pollution controls measures (Anderson and Fiedor, 1997). Reports are supposed to be verified by a third party. Permits and rates are issued annually by the national environmental ministry based on the current ambient pollution concentration, and temporary permits may be issued as well for firms that plan to implement pollution control measures.

Penalty fees: Firms operating without permits are subject to a penalty fee that is double the normal fee and exceeding the limit will incur a non-compliance fee charged on each unit above the allowable level (OECD, 1994). Firms emitting above the allowed threshold pay increasingly higher penalty rates for every year they do not reduce emissions; 20% for the first year, 40% for the second, etc.

Monitoring: Monitoring system began in 1992, and was fully operational by 1997. Its role is to revise ambient quality standards based on data, as well as assign inspectors to be responsible in verifying facility permits, accuracy of pollution levels and calculation of charges (Anderson and Fiedor, 1997).

Inefficiencies and Distortions (Blackman and Harrington, 1999):

1) Administrative

- Verification was difficult as emission levels were self reported and monitoring and enforcement was weak. Limited enforcement due to political concerns: in 1992, 40% of registered air polluters were operating without permits, and only 20% of the penalty fees were collected

- “Normal” fee payments counted as production costs and written-off as tax liabilities which reduce incentives to abate

- Large, state-owned firms, like power plants, are often supported with subsidies and waivers, which reduce incentives to abate

2) Exclusions

- Coal widely used at thousands of small fixed-point sources since residential heating is exempt from the fee system.

3) Distribution of Revenues

- Fees channeled into regulatory activities and environmental investments which create perverse incentives for government to maintain the fee system as a source of funds.

Evaluation

Theoretical Underpinning

The ideal Pigouvian tax rate prompts polluters to internalize external costs and emit to the point where marginal abatement costs (MAC) equal marginal social damages. In a second-best world, two-tiered pollution tax rates have been implemented to deal with uncertain marginal abatement costs. In the context of Poland, although firms no longer face a uniform price which detracts from cost effectiveness (Bluffstone, 2003), it has been shown that the “penalty” rates promote abatement (Blackman and Harrington, 1999). On the other hand because the “normal” the SO2 tax rates are set according to political and revenue considerations, rather than abatement costs and social damages (Anderson and Fiedor, 1997), the tax serves more as a fund raising mechanism than a tool to reduce pollution (OECD,1994).

Cost Effectiveness

Revenues from the tax are earmarked for environmental investments in the sector from which the pollution arose. Poland’s pollution fee system drives 40% of its environmental investments (OECD,1994). In 1996, USD $126.67 million was collected from the SO2 tax (Cotetea, 2011) and in 1997 total environmental funds amounted to $513 million which represented 0.4% of GDP (Bluffstone, 2003). 36% of these proceeds were distributed to a national fund, while 54% and 10% were allocated to regional and municipal funds respectively. It has been argued that the selection of projects do not always maximize net social benefits. Municipalities might invest in pollution abatement or control technologies that benefit their locales but are not cost-effective from a social point of view (Anderson and Fiedor, 1997).

Impact

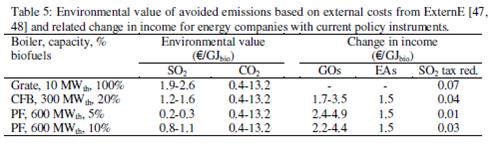

Coupled with stricter emissions standards the tax has contributed to reductions in SO2 emissions. Power plants have reduced consumption of coal, shifted to coal with lower sulfur content, increased efficiencies by installing flue gas desulphurization technology (Ericsson, 2007) as well as investing in other abatement technologies (Kudelko and Suwala, 2003). The table below shows the internalizing of environmental costs and savings to firms by substituting biofuels for coal in district heating plants (Ericsson, 2007). It has been argued that in the region, Poland might be the only country where fees reduced emissions of SO2 (Stavins, 2002).

Increasing the tax’s comprehensiveness by addressing the administrative distortions and including households would improve the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of the SO2 tax. A fuel tax on coal would be the most easily administered solution for households but could have regressive effects. To improve monitoring and enforcement some of the revenues generated from environmental fees could be directed towards expanding the capacity of these institutions. However, this would come at a cost of reduced funds for investment in environmental infrastructure. At the time of the most recent study we could obtain, Poland was on track to meeting its obligations in the Second Sulfur Protocol. The tax played an instrumental role in this success. Of the three objectives motivating the tax there is evidence to suggest it successfully promoted investment in abatement technology and generated national revenues.

References

Anderson, G. D. & Fiedor, B. (1997). Environmental Charges in Poland. C4EP Project. Discussion Paper 16. Retrieved from http://www.cid.harvard.edu/archive/esd/pdfs/iep/edp16.pdf

Blackman, A., & Harrington, W. (1999). The Use of Economic Incentives in Developing Countries: Lessons from International Experience with Industrial Air Pollution. Resources for the Future. Discussion Paper 99-39. Retrieved from http://www.rff.org/rff/documents/rff-dp-99-39.pdf

Bluffstone, R. A. (2003) Environmental Taxes in Developing and Transition Economies. Public Finance and Management.3 (1), p. 143 – 175. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID461539_code031026600.pdf?abstractid=461539&mirid=1

Cotetea. (2011, January 22). Study of pollution in Poland: SO2 emissions tax. Retrieved April 4, 2012, from http://www.bukisa.com/articles/441950_study-of-pollution-in-poland-so2-emissions-tax

Ericsson, K. (2007). Co-firing – A Strategy for bioenergy in Poland? Energy – The International Journal. 32, p. 1838 – 1847.

Harris, P. G. (2007). Europe and Global Climate Change: Politics, Foreign Policy and Regional Change. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kiuila, O. (1999). Economic Repercussions of Environmental Regulations in Poland: The Case Of The Second Sulfur Protocol. The Central and East European Economic Research Center at the Warsaw University. Retrieved from http://fmwww.bc.edu/cef99/papers/kiuila.pdf

Kiuila, O., & Sleszynski, J. (2003). Expected effects of the ecological tax reform for the Polish economy. Ecological Economics. 46, p. 103 – 120.

Kudelko, M., & Suwala, W. (2003) Environmental Policy in Poland – Current State and Perspectives of Development. Mineral and Energy Economy Research Institute.

Mitosek, G., Degorska, A., Iwanek, J., Przybylska, G., & Skotak, K. (2004). EMEP Assessment Report Poland. Institute of Environmental Protection in Warsaw. Retrieved from http://www.emep.int/assessment/poland.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (1994). Taxation and Environment in European Economies in Transition. Centre for Co-Operation with the European Economies in Transition. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=OCDE/GD(94)42&docLanguage=En

Paraschiv, S. L., Paraschiv, S. & Ion, I. V. (2011) The Profitableness of the Environmental Protection in a Thermal Power System by Setting the Optimum Level of the Environmental Taxes and Charges. Revista Thermotehnica. Retrieved from http://www.revistatermotehnica.agir.ro/articol.php?id=1156

Sofia Initiative on Local Air Quality (SILAQ). (1998). Reduction of SO2 and Particulate Emissions. The Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe. Retrieved from http://archive.rec.org/REC/Publications/SO2/SO2.pdf

Stavins, R. N. (2002). Experience with Market-Based Environmental Policy Instruments. Fondzione Eni Enrico Mattei Note di Lavoro Series Index. 52. Retrieved from http://www.feem.it/userfiles/attach/Publication/NDL2002/NDL2002-052.pdf