The Life of the Author

Humphry Tristram Potter (1747-1790)1 was born Born at Clay in Worcestershire to a pair of well-educated parents of respectable social standing.2 He secured a position as a preacher and on April 29, 1773 he was admitted an attorney in the Court of King’s Bench, and after that becomes a member of the English Court of Common Pleas.3 Potter’s success in managing his finances was a different story. In 1776 Potter went bankrupt, but thanks to his position in office he was able to avoid the much-dreaded debtor’s prison.4

Potter would encounter trouble sure enough, but it come not from his chequebook, but from his friends. One amongst them was Dr. Graham, who ran the Temple of Health in Pall-Mall. Failing to produce enough revenue from the Temple’s earnings, Dr. Graham rented the grounds out illegally to a group of cultists who worshiped a goddess of fortune.5 Still not content even with the added cash flow from the cultists, Graham decided he would make even more money if he transferred ownership of the property to someone else: his friend, Humphry Potter. Being a man of the law, Potter objected to Graham’s illicit activity. In an attempt to make the Dr. confess, Potter stormed into the Temple accompanied by a group of attendants and after a clash with the cultists, Potter seized control of the property.6

Here is when Potter’s misfortune begins. Rather than return the property to its former use, Potter decided to use the Temple in the same manner as Dr. Graham: by making money illegally through renting out the premises. Discovered by the authorities, Potter was fined, arrested, and imprisoned in Newgate for twelve months.7 Several years later, in 1786, a rival of Potter attempted to oust him from his place in office by accusing Potter of alleged malpractice. Potter insisted that his opponent’s argument was inadequate in supporting the charges. Unfortunately for Potter, his opponent pointed out Potter’s past illegal use of the Temple of Health some years earlier.8 The judges considered this a good enough reason for striking Potter off the roll of the Court of King’s Bench. Not long after, Potter was called to court again and struck off the roll for the Court of Common Pleas.9 In 1788 Potter is sent to prison a second time, again for a year, in addition to having to stand in the pillories.10

Potter died in 1790 at a public house near Lant Street, Southwark, and his remains were decently interred.11 The editor of Potter’s dictionary, who provided the above details of Potter’s life, is of the opinion that Potter committed his crimes as a result of giving into temptation rather than being inherently malicious. He also comments that Potter had many close friendships and few were as knowledgeable of Crown Law as Potter.12 To conclude, the editor claims that the bottom line is that Potter’s actions did not always line up with his intentions.13

The Dictionary

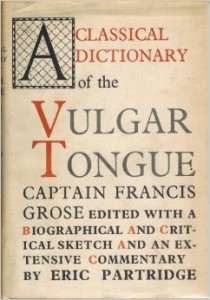

Overview

Potter’s book was entirely composed by himself, and dedicated to William Addington, a justice of the peace.14 The editor tells us that Potter had friends of every rank and background, which provided him with firsthand exposure to cant and flash.14 The editor also claims that this dictionary is one of the best examples of its kind, suggesting that the relationships that Potter held with his friends were key to the writing of a cant and flash dictionary of such quality.15

Physical Appearance

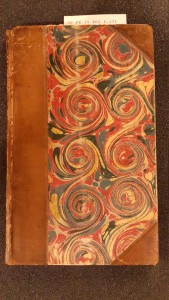

Front cover

Potter’s Dictionary is quite eye-catching. The cover features a colorful swirl pattern that has withstood the test of time. Another physical attribute that stands out is the size. One would assume that a dictionary such as this one, that aims to encompass the languages of cant and flash would be exceedingly large. At a mere 69 pages in length, it goes against this expectation of size. It could be that this dictionary contains the foundations of cant and flash, or that it contains the most commonly-used terms. Either way, it warrants a closer look at what lies behind the cover of this book.

The Contents

Cover Page

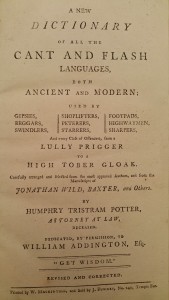

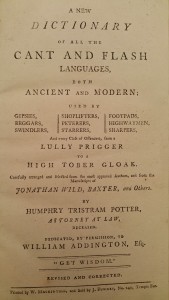

Cover Page

Here we are presented with the cover page. First, there is the title which consists of title, and then an extensive description detailing the types of language, cant and flash, and the groups that use these languages: gypsies, beggars, and an assortment of criminals. The description continues by providing a number of key names: Jonathan Wild and Baxter as two sources, and Potter as the compiler of the information from these sources. Finally, the cover page dedicates the work to William Addington and at the very bottom line it includes the publisher’s information.

Preface

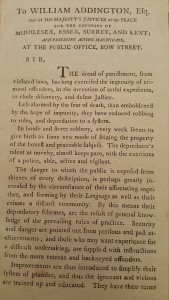

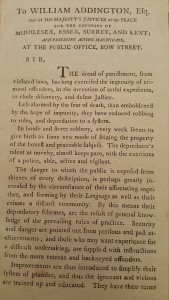

Like the cover page, the preface includes words of dedication to William Addington. It then continues with a description of crime, the arms race between criminals and enforcers of justice, and the danger that its practitioners pose to the public. Potter cites criminal jargon, or cant, as one of the ways in which criminals operate; by disguising their intent through creating their own language and codewords, criminals are able to dupe their victims and avoid detection. Potter then describes that the primary purpose of his dictionary is to reveal the secret language of criminals to the reader, thus allowing the reader to protect himself from their nefarious ways, or to capture them if the reader should be a member of the police.

Like the cover page, the preface includes words of dedication to William Addington. It then continues with a description of crime, the arms race between criminals and enforcers of justice, and the danger that its practitioners pose to the public. Potter cites criminal jargon, or cant, as one of the ways in which criminals operate; by disguising their intent through creating their own language and codewords, criminals are able to dupe their victims and avoid detection. Potter then describes that the primary purpose of his dictionary is to reveal the secret language of criminals to the reader, thus allowing the reader to protect himself from their nefarious ways, or to capture them if the reader should be a member of the police.

Names of Offenders

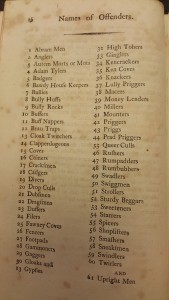

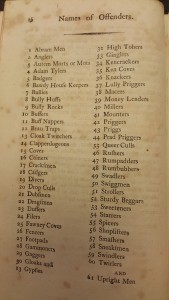

Names of offenders (page 16)

On this page we see a list of the names of 61 different types of offenders, from Abraham Man (1) to Upright Man (61). It is reasonable to assume that these would have been the most notorious types of criminals, and thus considered to be the most important to include at the beginning of the book, before the list of definitions. By listing the types of criminals, the reader also gets an idea of the most common types of crimes. While we as modern readers might be unsure of what kind of crimes a Gingler (33) or a Knacker (36) might have practiced, others such as Shoplifter (56) and Sturdy Beggar (52) are much more familiar; we still use the term shoplifter, and while its meaning might have been different in the eighteenth century, its association with crime is undeniable and familiar. Gypsie (31, written unintentionally as 13) is of especial interest since the inclusion of this word on the list speaks of the longtime association of gypsies with crime.

Definitions

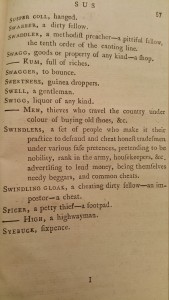

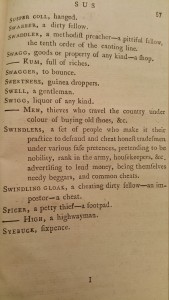

Definitions (page 57)

Here we have a sample page from the main “definitions” section of the dictionary, in the S part of the alphabet. Especially interesting to note is that the definitions of several of the offenders from the earlier list are given here. Swaddler, which appears in place #49 on the earlier “Names of Offenders”, is defined here as “a methodist preacher – a pitiful fellow, the tenth order of the canting line”. Spicer, which takes place #55 on the list is defined as, “a petty thief – a footpad”; footpad is offender #27 on the list. We see then that the types of criminals listed at the beginning of the dictionary are then defined later in the dictionary. This suggests that the reader of the dictionary would not have known what a footpad, or a spicer, or a swaddler was, otherwise the definition for each offender would not have been given. This reveals that these names would have been created by criminals for each other, rather than by the public to describe said criminals. A final note should be had on the fact that the dictionary titles itself as a dictionary of flash terms, as well as cant terms. The slang of the upper class, the flash element of the dictionary can be seen in the inclusion of words such as Swagg, “goods or property of any kind”, and its variation Rum, “full of riches”. In this way, while primarily focused on combating crime through listing words that make up its language, Potter’s dictionary contains a significant element of flash terms as well.

Conclusion

We see then that Potter’s A New Dictionary of all the Cant and Flash Languages is more than a mere dictionary; it is a product of his life and life’s experiences. It contains the language that he learned from his acquaintances, who came from both the criminal underworld and the upper class of England, bringing their cant and flash respectively. Most significantly, it is a tool. It teaches the reader the language of criminals and grants the knowledge that Potter felt would allow those who read his dictionary to detect criminals and criminal activity, and thus avoid it or bring justice to the perpetrators.

1 http://thesaurus.cerl.org/record/cnp00036814

2 Potter, Humphry Tristram. A New Dictionary of all the Cant and Flash Languages. London: Printed by W. Mackintosh, and sold by J. Downes, No.240, Temple Bar, 1796. RBSC call # SP PE 25 R62 V.271. Page 5.

3 Potter, 8

4 Potter, 8

5 Potter, 10

6 Potter ,11

7 Potter ,11

8 Potter ,12

9 Potter, 13

10 Potter, 13

11 Potter,14

12 Potter, 14

13 Potter, 15

14 Potter, 15

15 Potter, 15