Describing Communication Technologies

Below is my final project for ETEC 540 and describing communication technologies. I chose to follow the evolution of the letter “A” through time and how the evolution of a single letter has impacted our culture, education, and literacy.

Click the image below to begin the presentation (opens in new window):

TRANSCRIPT: SLIDE 1: TITLE SLIDE [SLIDE TEXT: The Letter A through time: Evolution of a single letter and its impact on literacy] Did you know that the simplest, most fundamental letter in our alphabet - the letter “A” - was once not a letter at all? The letter "A" hasn’t always looked the way it does today. In fact, it started as an ox head and its evolution tells a much bigger story than you’d expect. The evolution of the “A” perfectly illustrates the reciprocal relationship between communication needs, invention, and literacy practices. Let’s take a quick journey through 4,000 years of the evolution of the letter “A”. SLIDE 2: A BRIEF HISTORY [SLIDE TEXT: A Brief History: Why study one letter? The letter “A” as a lens into writing technologies IMAGE: Capital letter A in Times New Roman] Why study one letter? The letter “A” is a lens into writing technologies. It’s simple and familiar, and often the first letter children learn. The history of “A” shows how communication needs, invention, and literacy practices shape one another. In this course, we’ve learned that writing is a technology, one that reshapes human cognition, culture, and education (Postman; Ong). Typography itself is a literacy technology. Every change in how we wrote the letter “A” emerged because people needed to communicate differently and each shift reshaped how people read, learned, and thought. SLIDE 3: WRITING BEGINS [SLIDE TEXT: Where Writing Began: Writing began as a way to keep records; “A” wasn’t just a letter - it was a technological solution to a communication problem, reshaping literacy. Proto-Sinaitic A: ~1,750 BCE from the Semitic word ‘alp, meaning “ox” IMAGE: OX HEAD] Our story begins around 1800 BCE with Proto-Sinaitic, the earliest known alphabetic script. Early societies depended on oral culture using memory, rhythm, and formulaic thinking (Ong). Reading was limited and symbolic. As trade expanded, people needed record-keeping tools that didn’t rely on memory, prompting new communication systems. This pressure produced early symbols, including the Proto-Sinaitic ancestor of A: an ox-head pictograph (from the Semitic (suh·mi·tuhk) word “alp”, meaning “ox”). Material needs pushed societies toward symbolic writing (Gnanadesikan, 2019). Here, “A” wasn’t just a letter - it was a technological solution to a communication problem, reshaping our literacy. SLIDE 4: THE ALPHABETIC REVOLUTION [SLIDE TEXT: The Alphabetic Revolution: The birth of phonetic literacy. As the letter “A” changed, reading became more accessible and human cognition shifted with it. IMAGE: Phoenicians ~1000 BCE, Simplified the ox head into an Aleph; GREEKS ~750 BCE Turned Aleph into Alpha, a vowel; LATIN ~500 BCE Archaic Latin] As writing systems evolved, people needed symbols that were quicker to write, more adaptable, and easier to teach. The Phoenicians simplified the ox-head into Aleph (aa-lef), an abstract form suited to their writing tools - reeds and ink. This shift was driven by material constraints and views writing as a material practice (Haas, 2013). The Greeks then turned Aleph into Alpha, a vowel, allowing writing to represent spoken sounds. This transformation reshaped literacy and cognition, demonstrating that language shapes thought (Boroditsky, 2019). Culturally, manuscripts belonged to elite literate communities. But the alphabet made reading accessible to everyone. As the letter “A” changed, reading became more accessible and human cognition shifted with it. SLIDE 5: TOOLS SHAPE TEXT [SLIDE TEXT: Tools Shape Text: Stones and chisels = straight shapes; Parchment & quills = curved shapes; The shape of the “A” and our writing system has always been shaped by the tools we had to create it. IMAGES: Roman, ~1 CE; Modern Latin, today] The change in the shape of the "A" didn’t happen just because people felt like it. Its shape reflects every writing tool humans have used. The Romans carved letters into stone with chisels. This made it much easier to create an “A” shape with straight lines and serifs, and it looked more similar to how we shape the letter "A" today. In medieval Europe, parchment and quills allowed more curved, flowing forms. These shifts echo Haas’ (2013) claim that writing is deeply tied to physical materials and technologies. SLIDE 6: MECHANIZATION AND STANDARDIZATION [SLIDE TEXT: Mechanization & Standardization: Print - Print wasn’t just a faster way to copy text - it fundamentally reorganized knowledge.; Mass Literacy - Print standardized “A” and text globally, which supported the rise of mass literacy.] With the printing press, literacy entered a new phase. Print didn’t just speed up copying - it reorganized knowledge itself (Bolter; Innis). Gutenberg’s “A” mimicked handwriting, but printers soon redesigned it to be clearer and more geometric. Print standardized the letter “A” and text more broadly, supporting mass literacy, schooling, and the rise of authoritative textbooks (Scholes). Print didn’t just stabilize “A”’s form - it shaped how generations learned to read. SLIDE 7: DIGITAL WRITING & THE LETTER A [SLIDE TEXT: Digital Writing & The Letter A: Digital technologies didn’t replace print—they rebuilt and transformed it.; Pixel (Low-resolution displays forced blocky forms.), Vector (Vector fonts and anti-aliasing restored curves.), Variable (Adjust dynamically based on screen size, user needs, accessibility.) Finally, the digital age. Finally, the digital age. Bolter (2001) describes digital writing as a remediation of print, visible in the pixelated “A” of early screens. Low-resolution displays forced blocky forms, while vector fonts and anti-aliasing restored curves. Today, variable fonts adjust type dynamically based on screen size, user needs, and accessibility. This reflects Week 5’s themes: digital writing is fluid, personalized, multimodal, and scroll-based. A digital “A” isn’t fixed - it's many shapes adapting to its users. This matters for education: screen-optimized fonts (Verdana, Georgia) and accessible designs like OpenDyslexic show how digital type can literally reshape reading. SLIDE 8: CONCLUSION [SLIDE TEXT: What does the letter A teach us? It’s a living record of 4,000 years of text technologies and the literacy practices they made possible. Writing as technology; Materiality shaping form; Shifts from oral to literate cognition; New forms borrowed from old; Change driven by invention] So what does the evolution of the letter “A” teach us? Bringing this back to what we’ve studied in this course: Writing as technology (Postman, 2011) Materiality shaping form (Haas, 2013) Shifts from oral to literate cognition (Ong, 1982) New forms of media often borrow from and reshape older ones, leading to a constant evolution (Bolter, 2001) Cultural and educational change is driven by invention The letter “A” evolved because humans needed new ways to communicate - and each transformation reshaped how we read, think, and learn. So the letter “A” isn’t just a letter: it’s a living record of 4,000 years of text technologies and the literacy practices they made possible. SLIDE 9: THANK YOU Thank you for watching my presentation and I look forward to your feedback. SLIDE 10: REFERENCES Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Gnanadesikan, A. E. (2009). The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. Wiley-Blackwell. Haas, C. (2013). The technology question. In Writing technology: Studies on the materiality of literacy (pp. 3-23). Routledge. Innis, H. (1951). The bias of communication. University of Toronto Press. Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. Methuen. OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (GPT-5) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat Postman, N. (2011). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. SAR School for Advanced Research. (2017, June 7). Lera Boroditsky, How the Languages We Speak Shape the Ways We Think [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGuuHwbuQOg&t=1s Scholes, R. (1998). The rise and fall of English. Yale University Press. Writing tools image from: ChatGPT AI Disclaimer: I used ChatGPT for generating ideas on how to structure my presentation, helped me with an outline, and used it to revise my writing for grammar and clarity. All final edits and ideas are my own.

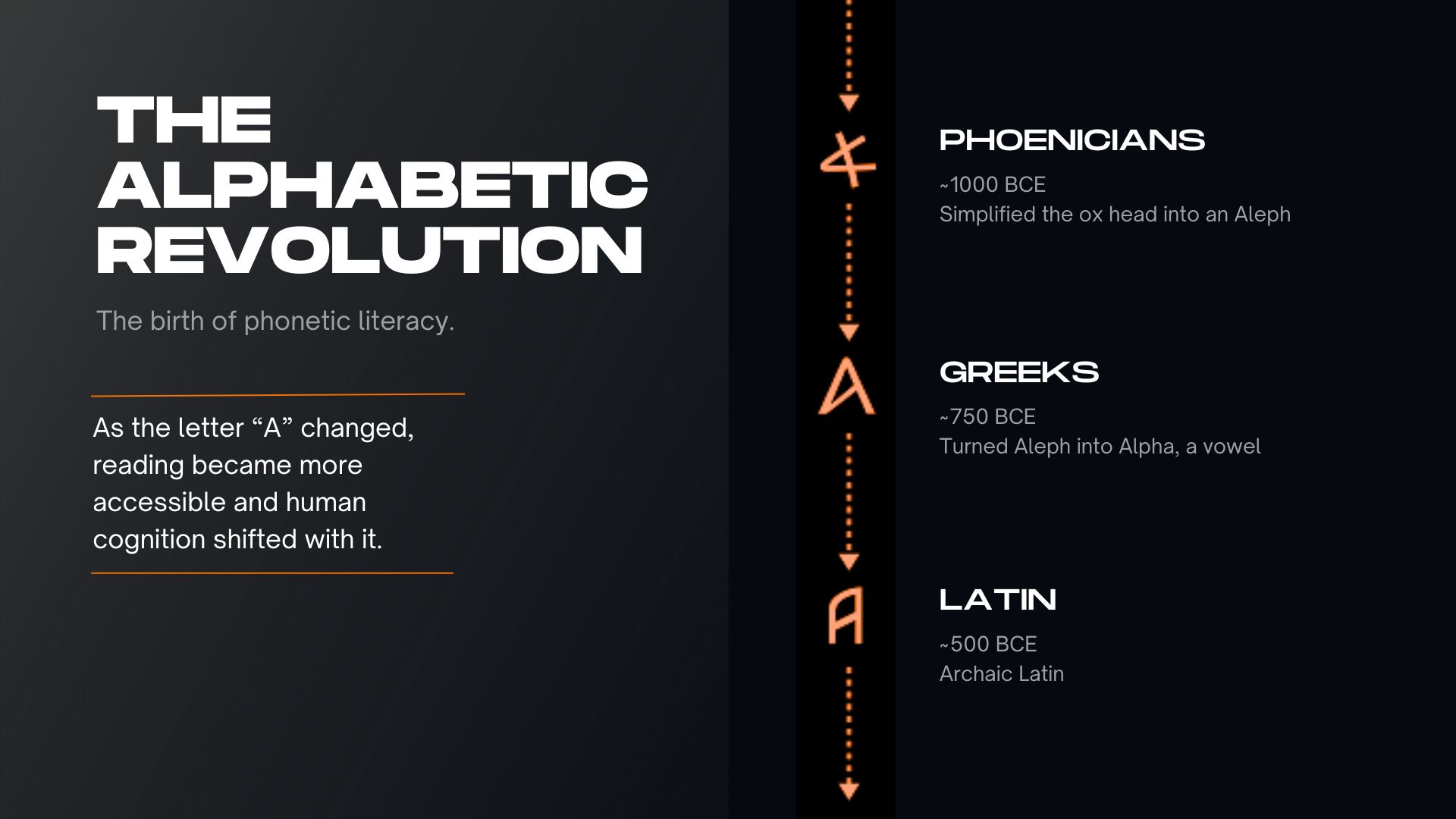

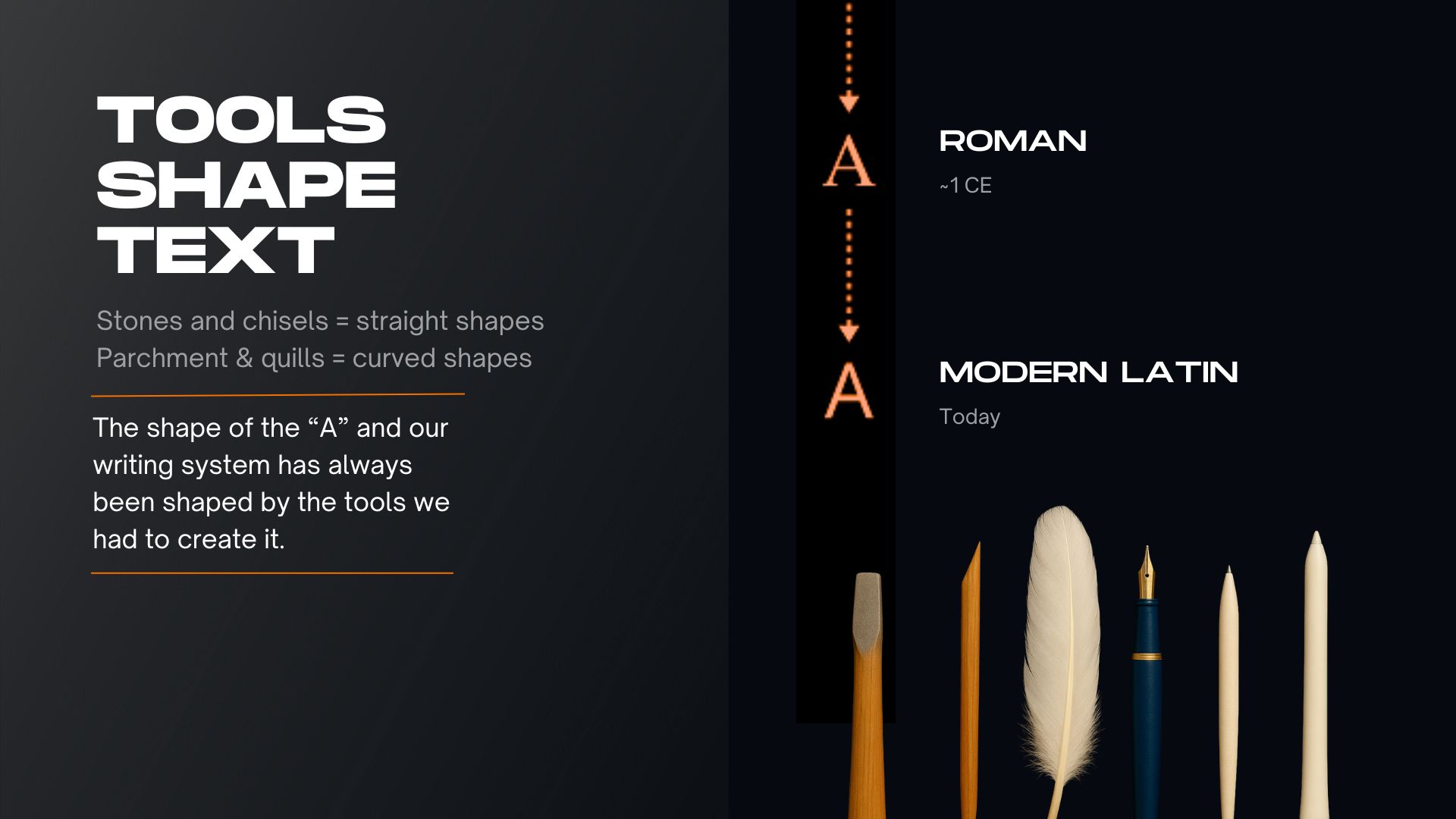

All Slides