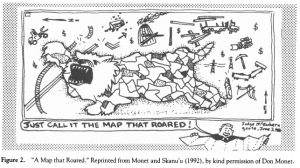

3] In order to address this question you will need to refer to Sparke’s article, “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” You can easily find this article online. Read the section titled: “Contrapuntal Cartographies” (468 – 470). Write a blog that explains Sparke’s analysis of what Judge McEachern might have meant by this statement: “We’ll call this the map that roared.”

In his article section regarding Contrapuntal Cartographies, Sparke addresses the tense differences and disagreement in court between federal and BC government, and the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people. In the debate, the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people “attempted to outline their sovereignty in a way that the Canadian court might understand.” (Sparke 468). This is significant in that it leveled the playing field, in a way, between the two sides: the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people were viewed as less literate, and less knowledgeable – and everyone in the courts, including Chief Justice Allan McEachern himself, knew this. By providing a map that served to outline in detail the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people’s “roaring refusal of the orientation systems, the trap lines, the property lines, the electricity lines, the pipelines, the logging roads, the clear-cuts, and all other accouterments of Canadian colonialism on native land” (Sparke 468).

McEachern’s referring to the map as a “map that roared” was something that illustrated his own perception of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people changing in light of this genre of cartography in which he, himself, was illiterate. Because of this, Judge McEachern, perhaps feeling slightly threatened, would eventually rule against the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people in the court. In Sparke’s analysis of what McEachern alluded to, he drew a connection to a satirical movie about the Cold War era, called “The Mouse that Roared.” This reference drawn toward a “Map that Roared” essentially outlined an unexpectedly loud, defiant voice that came from an unexpected source: the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people. McEachern ultimately acknowledged the map’s power and the people taking action to stand up for their land by calling it as such.

Although Judge McEachern ended up ruling in favor of the defense, against the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people, the Supreme Court would eventually overturn his decision and call for a new trial. This was especially significant in that this served as a turning point, of sorts, for First Nations in Canada fighting for – and winning – some of their rights back. What was most impressive was the fact that map that was presented was the product of the oral stories of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people, passed down from countless generations. The significance in this cannot be overlooked: contrary to popular belief, oral histories and stories do, indeed, hold a significant weight in influencing the decisions made in the courts of law.

Works Cited

“Office of the Wet’suwet’en.” Office of the Wet’suwet’en. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 June 2016.

“Our History.” Recent History. Gitxsan Development Corp, n.d. Web. 29 June 2016.

Sparke, Mathew. “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88.3 (1998): 468-470. Web. 29 June 2016.