Explain why the notion that cultures can be distinguished as either “oral culture” or “written culture” (19) is a mistaken understanding as to how culture works, according to Chamberlin and your reading of Courtney MacNeil’s article “Orality.”

In his influential work, Wealth of Nations, published 1776, Adam Smith introduced the idea of stadial history, which assumes that all civilizations will develop in the same manner: from pre-agricultural (aka “savage”), to early-agricultural (aka “barbaric”), to industrialized (aka “civilized”). According to this line of thought, an explorer such as George Vancouver who “discovered” the Maori in New Zealand would really be meeting a version of his great-great-great-great-great… grandfather. (Remarkably, this mode of thinking—also called, unilinearism—has influenced non-European writers themselves—most notably black abolitionist Equiano, who argued in The Interesting Narrative (1789) that emancipated Africans would be a greater benefit to the British economy, since the entire continent of Africa would inevitably “adopt the British fashion, manner, and customs.”

Stadial, or conjectural, theory has been a key culprit in reinforcing the false dichotomy between oral and written culture. In her article “Orality”, Courtney MacNeil details how oral cultures have traditionally been associated with tribal groups while written cultures are ‘proof’ of more ‘advanced’ civilizations. Both MacNeil and J. Edward Chamberlin cite the Toronto School of Communication as a major advocate of the primacy of the written word and the “primate-cy” of the spoken word.

In his book If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories?, however, J. Edward Chamberlin, takes a different stance. He collapses the binary between oral and written traditions:

All so-called oral cultures are rich in forms of writing, albeit non-syllabic and non-alphabetic ones… On the other hand, the central institutions of our supposedly ‘written’ cultures… are in fact arenas of strictly defined and highly formalized oral traditions… (Chamberlin 19)

Chamberlin argues that every culture’s are invested in both oral and written elements, which are inextricably “entangled with each other” in our stories and songs. I can attest to the fact that this certainly holds true in Chinese culture. In our 5000 years of recorded history, we have accumulated a rich literary (poems, ancient texts, calligraphy) and oral (folk songs, operas, chants) repertoire. Oftentimes, these interface and overlap. For example, operas are written down so that they can be performed; books of poems, vice versa, are committed to memory in school.

Today, digital “literature” also upends common assumptions about and blurs the lines between these two types of media. For example, audio-recording sites like Youtube preserve orality by allowing them to be replayed while instant messaging and social media prove that text-based communication no longer holds permanence. Even the existence of this online classroom—ENGL 470A—is proof that “technological advances in communication have been part of the impetus to rethink the divisive and hierarchical categorizing of literature and orality” (Paterson). Our “lectures” are have once again come back to the original sense of the word—to read—what Professor Paterson had to “say” about Lesson 1.3. (Her introductory vlog, on the other hand, is oral.)

Instead of distinguishing culture as either oral or written, we might think dialectically of culture as both. Courtney MacNeil is careful to make a distinction between and oral and orality, however. Borrowing from Meschonnic, she writes, “orality is not the opposition of writing, but rather a catalyst of communication more generally, which is part of both writing and speech” (Orality). Orality is a means of communication, a means of accessing collective memory or innate human truth, and oraliture, coined by Edouard Glissant, a repository of both written and verbal arts.

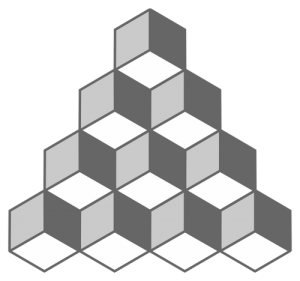

One last point: the principle of superposition within quantum theory posits that something can exist in multiple states at the same time. (For example, are these cubes facing in or out? Both.) The truth about stories is that they can be both oral and written. Like this optical illusion, however, sometimes it’s difficult to recognize its dialectical nature. In the rest of his book, Chamberlin goes on to deconstruct other dichotomies—home and homeless, reality and imagination—and helps us see that these contradictions can coexist symbiotically. It is only when we can come to terms with these states of superposition that we will be able to participate in these “ceremonies of belief” and enter into one another’s stories.

Works Cited:

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Reimagining Home and Sacred Space. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2004. Print.

Necker Cube Illusion. Digital image. Web. 23 Jan. 2016. <publicdomainvectors.org>

MacNeil Courtney. “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. Uchicagoedublogs. 2007. Web. 19 Feb. 2013.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 1.3.” ENGL 470A Canadian Studies: Canadian Literary Genres. University of British Columbia, 2013. Web. 6 Jan. 2014.