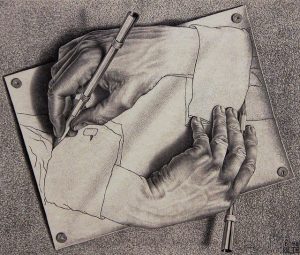

What is our relationship to technology? Despite differing on degrees of analysis, the four authors below all posit that our relationship to technology is a reflexive relationship (X influences/constitutes the development of Y which influences/constitutes the development of X…Y…X…Y…etc).

Creative commons license

From the readings, both Ong (1982, p. 78) and Postman (1992, p. 3-20) discuss Plato’s Phaedrus, a story about the invention of writing and arguments against it as a threat to things such as human memory. This is a story quoted at length elsewhere (see, for instance, Norman, 1993, p. 45) for it introduces a dual cognitive dissonance: that writing and literacy could be considered a threat in the past, when writing is considered an essential and traditional component of our world; and that we see in our world echoes of these same arguments pitted against modern innovations, such as the computer.

Postman positions writing as being one in a long line of developments that has seen technology slowly come to dominate culture to our detriment. Initial success with technology, argues Postman, have seen the technological worldview spread into spheres where they do not belong. For Postman, “technopoly” refers to a situation where our brains and societies are hijacked by a subordinate relationship of humans to technology, it becomes the solution for everything (Postman, 1992).

Norman (1993) argues that technologies (he uses the term ‘physical artifacts,’ and includes writing) per se are not the issue, but that care must be taken to design artifacts to fit and augment humans. Whenever such care is not taken, Norman argues that we don’t reap the benefits of technologies. Namely, by identifying technology as physical artifacts in a reflexive relationship with cognitive artifacts: physical artifacts are created through cognitive artifacts, and these physical artifacts then shift the user’s cognitive artifacts (one can see a Vygotskian view of tools at work). Norman further contends that the modeling inherent in many of our technologies simply makes us better thinkers able to solve more problems. The alternative to adapting technology to suit humans (incidentally Norman directly quotes Postman when ending his book), is a “machine-centred” view where humans conform to machines. This is where Norman situates design as a humanizing force, one where we focus on designing technology to fit humans.(Norman, 1993, p. 253)

Ong (1982) approaches the topic through writing/reading (literacy), which he frames as a technology and perhaps the single most impactful technology of all. So successfully has this technology integrated with our culture that we don’t consider it technology at all. Ong speaks directly of the effects of literacy as a technology and takes the view that this version of technology has impacted the cognition of humans, shifted conceptualizations of the world, and changed the way we communicate with one another. Perhaps a broader implication of Ong’s analysis is that, while most technologies are smaller in scale than writing (for Ong writing is one of the most powerful technologies ever created), technology generally impacts human cognition; we create technology and then technology creates us.

One author seems to have adopted Ong’s view that literacy changes psychology and built upon this concept. Rifkin (2009) first argues that, indeed, innovations like writing have made enabled us to extend empathy to ever larger scales (Rifkin even cites the same Soviet text as Ong, A. R. Luria’s “Cognitive Development: its cultural and social foundations”). Rifkin then takes the discussion in the ecological direction: our technologies (the ones helping us come together) require more and more resources, which may cause our extinction but may make us smart enough to avert this extinction. The reflexive relationship here extends from physical artifacts (e.g., agriculture), begetting physical constraints (e.g., logistics problems surrounding population booms), begetting physical artifacts (e.g., writing), begetting psychological shifts (e.g., religion), etc. The entire time this is happening, we and our already-created technologies (e.g., writing) continue to adjust and adapt.

Focused on writing, the authors above (Postman, Norman, Ong, Rifkin) all point out that our relationship to technology is a reflexive give-and-take relationship that changes over time. Technology shifts how we view the world and ourselves, and these three all change as new technologies are developed. While one can opine this reflexive process as a good or bad thing, it seems more like an inevitability of the human condition or, as Ong more cogently states: “Technologies are artificial, but…artificiality is natural to human beings. Technology, properly interiorized, does not degrade human life but on the contrary enhances it.” (Ong, 1982 p. 82)

References:

Norman, D. (1993) Things that make us smart: Defending human attributes in the age of the machine. New York: Basic Books.

Ong, W. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Rifkin, J. (2009). The Empathic Civilization: The race to global consciousness in a world in crisis. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

EdPawliw

June 3, 2018 — 4:00 pm

I totally agree that technology has a reflexive relationship with humanity, on a societal and individual basis. From the societal viewpoint, we are much more aware and more able to communicate with others that are outside our local and extended community groups. We have widened our reach while also striving to make these technological reaches more like an in-person experience, and the circle continues as you allude. If we look at our ETEC cohort, we are able to advance our knowledge alongside our peer-group, supporting each other from afar. Through multiple modes we are empowered to communicate through means such as verbal, visual, and literary modes via digital technology. By this process we see how we are each finding new-to-us ways of using technology to support the conversations we otherwise could not have at the distances we are all at.

The relationship between technology and the individual is much more nuanced. Each person will have their personal philosophy on the utility technology will have and thus the effect it will exert on and the power it will have over that person. If I believe that linguistics involves employing a form of technology and you do not, then we will perceive this interaction very differently. To take an example from the world of music, some artists use external instruments to express themselves musically, while a vocalist uses their internal vocal cords. Both of these result in an external expression, so would these not be considered technology used to communicate musically? Some would think so, while others may not. Ong (2013) states that “Sustained thought in an oral culture is tied to communication thinking in mnemonic patterns, shaped for ready oral recurrence”. If one thinks of songs as patterns, does not orality begin to sound a lot like musical expression? So in a manner, any and all communication is a form of externalized expressive technology. Candler (1995) says “that orality and literacy are equivalent linguistic means for carrying out similar functions”. If these are essentially one and the same, then communication is essentially an application of technology, and has been through the history of the Homo sapien. We have been on an evolutionary path that has developed technology for communication and each iteration has been designed to allow us to communicate more efficiently. A close look at where digital technology has allowed us to progress as far as synchronous and asynchronous communication, one can conclude that we are getting ever closer to the in-person experience using technology. In essence, we are developing technology to provide us with what we already have, but on a global scale. And the continuance of the round-about relationship we have with technology as you mention continues.

References:

Chandler, Daniel. “Biases of the Ear and Eye.” Media Representation, 18 Sept. 1995, visual-memory.co.uk/daniel/Documents/litoral/litoral2.html.

Ong, Walter J.. Orality and Literacy : 30th Anniversary Edition, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/detail.action?docID=1092747. Created from ubc on 2018-04-21

mackenzie moyer

June 7, 2018 — 6:08 pm

I hadn’t considered it from an individual or musical position, thanks Ed :). I feel as though even my own individual relationship to technology changes from day to day. Generally, there’s a common thread of addiction and rose-tinted-ness to my interactions with technology, but I’m very very slow to adopt certain things (I finally invested in my first smart-phone last year, and had been without a cell, dumb or smart, for some time before then). On the other hand, when I do adopt, I’ll sometimes spend an inordinate amount of time learning the ins and outs of new tech.

Thanks for the thoughts,

Mackenzie