The radio broadcast, From Papyrus to Cyberspace, brought to mind the concept of a distributed cognitive network. At approximately 41:34 in the broadcast, it is made mention that,

“The written word has always throughout history given us the power to, and in the jargon of the late 20th century, outsource our knowledge” (Engell & O’Donnell. 1999).

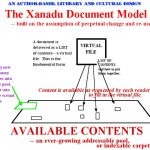

Giere & Moffatt (2003) mention that the focus should be on the process or system and not the product that results from the distributive function (Giere & Moffatt. 2003. P.303). They go on to say that this system entails not only humans, but also “many external representations and other artefacts” (Giere & Moffatt. 2003. P.304). This distributed cognitive network has brought about many benefits such as the democratization of society, support communities through technology, increased ability for academic dialogue, and publishing time sensitive information (Engell & O’Donnell. 1999). The evolution of our information, communication, and knowledge networks has been ongoing since print technology was made accessible to the masses and continued with the advent of radio, and now multimedia digital technology.

With each iteration of advancing representational technology layers of concern with intellectual authority, copyright, and fair use are raised. Difficulty in verifying quality of material, corrupt and poor scholarship give rise to further questions. Previously there was a gatekeeper function that provided a filter of sorts for that which was presented for publication that could be missing from digital submissions (Engell & O’Donnell. 1999). Fahrenheit 451 penned by Ray Bradbury illustrates a society attempting to control text technology. Rather than taking this type of dystopian position, the key is instead to educate the consumers of text. Setting up learners with strategies to vet information is not a new concept. Academia has peer review and cited referencing to ensure the veracity of sources. With the evolution of forms of text, we must also evolve our investigative strategies. Presenting a blueprint that can illustrate a viable plan that learners and consumers of text can use as a starting point must become an imperative if we want to continue the democratization of society.

Teachers have many sources we can turn to that support educating learners how to be informed consumers. One site that provides guidance, hostingfacts.com, presents a concise reference for evaluating digital resources. The fact that evaluating resources has not and should not be a static concept must be reinforced in our students. As text technologies evolve, the methods to make sure our distributed cognitive network is based on a rigorous examination of sources must also evolve.

References:

Bradbury, R. (1967). Fahrenheit 451. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Engell, J. (Presenter) & O’Donnell, J. (Presenter). (1999). From Papyrus to Cyberspace [radio broadcast]. Retrieved from https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/4290/files/609973/preview

Giere, R. N., & Moffatt, B. (2003). Distributed cognition: Where the cognitive and the social merge. Social Studies of Science, 33(2), 301-310. doi:10.1177/03063127030332017

Hutchins, Edwin. Cognition in the Wild. MIT Press, 2006, uberty.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Edwin_Hutchins_Cognition_in_the_Wild.pdf.

Stevens, J. (2016, August 3). The Complete Guide to Evaluating Online Resources – HostingFacts.com. Retrieved from https://hostingfacts.com/evaluating-online-resources/

Stephanie Kwok

June 8, 2018 — 10:34 pm

Hi Ed,

Thank you for the enjoyable post. There were a lot of solid arguments in your discussion. Undoubtedly, the advances in technology have resulted in an abundance of benefits and conveniences for the world; we are able to communicate with others across the globe instantaneously without having to leave the comfort of our homes, and we have developed global shared-knowledge networks that have aided in improving medical and scientific developments enormously. However, as a society we are almost blinded to the consequences of technology use that have accompanied these very benefits.

In terms of online research, the sheer volume of non-vetted information available on the Internet is mind-boggling, and frankly, I don’t believe there is any possible way to moderate or contain it. I agree with your point, that rather than attempting to control text technology, “the key is instead to educate the consumers of text”. We should focus on teaching children to become more technologically literate as well as active in their vetting of online information. In doing so, we will also be able to target issues concerning intellectual authority, copyright, and fair use as you have mentioned. The website you linked would make an excellent classroom resource, and I like how it is comprehensive and well laid-out.

Additionally, I believe we should put more effort into organizing information that has already been vetted, in order to create more reliable databases to which we can turn to for trusted information. For this reason, I agree with Willinsky that there should be open-access of educational research to the public (Willinsky, 2002). From what I understand, many educational institutions still pay for the right to provide open-access to their students, but perhaps one day in the future we will be able to somehow extend that access to the general public also.

References:

Willinsky, J. (2002). Education and Democracy: The Missing Link May Be Ours. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 367-392.

EdPawliw

June 17, 2018 — 8:11 pm

Hi Stephanie

Your last point is an excellent one. The more scrutiny we can have with accompanying constructive feedback, the more confident we can be in relying on the information. I had an article come across my news feed that discusses how posting a research paper on-line opens it up to wider scrutiny that can point to errors in such things as methods used and sample group makeup. If we look at the Wikipedia model, the users of the site hold those contributing to a standard that require citations to help maintain integrity and reliability. If an open access Wiki-resource was created with academic research papers as the subject (with all sorts of topic sections and sub-sections of course), these could be peer reviewed prior to final post. The contacts we make for our distributed cognitive network could be used to elicit peer review, while also opening it up to a wider base of experts that may not yet be in our network. How this would look or be managed would be in the hands of the technology visionaries.