I am going to tackle this from a personal historical context to set perspective for the viewpoint to follow. My first teaching assignment was in 1991 in a small school populated by about 250 students from Kindergarten through grade 12. It was a 10 hour drive from my home town, in another province, and with an unfamiliar curriculum. My teaching assignment was mainly Industrial Arts (applied technology). The school was in a rural setting where some students spent up to 3 hours a day on the bus, split between getting to school and then returning home. I mention this to create a bit of an image of the isolated nature of this community and the limited access to local support. After finding out I got the job, and having an industrial shop as a classroom, I needed to go on a fact finding mission to see what equipment was there and what topics within the Industrial Arts curriculum I would be able to teach. Upon arrival, the classroom was a bit scattered. While my teacher training and trades and technical based background provided me with the knowledge I needed for areas such as small engines, welding, photography, and woodworking, I had no clue about other areas, most specifically screen printing, ceramics and leatherworking. These did not appear in the curriculum of my home province. Hunting around the facility I found a couple old how-to books but no class sets. There was a distinct lack of text books as well. Needless to say, I had some work to do to prepare resources for the classes. I spent hundreds of hours authoring booklets that the students could use as this was a multi-activity lab (multiple areas such as welding, woodworking, photography, and ceramics running concurrently). Owing to this it would have been impossible for me to teach all theory and procedures to each group at the same time, so the booklets became the vehicle through which the students independently attained the information they needed to get them started. These were, of course, heavily text based with a few photocopied pictures thrown in when necessary. Once created, these had to be photocopied. Thank-goodness the school educational technology had advanced past the spirit duplicator.

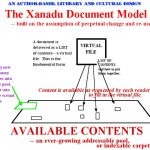

Flash forward almost three decades and reflect on the options available to produce resources for learners. First off, text-based resources are still out. These do not stay current long enough to be an economically viable supporting educational technology. Information booklets must still exist in some form for the students. These are still produced, but are now located on the course LMS (Learning Management System) pages, ever evolving, in digital format. The biggest difference between content is it is no longer constrained by paper as Ted Nelson mentions at approximately the 5:52 mark of his Google Tech Talk . Where once text was augmented with a few visual stills, now there is the ability to use many of our sensory inputs to augment text. These include auditory, both still and live action visuals, as well as the original textual format. Nor is the teacher the only source of information. The students can construct their learning experience seeking how much additional information they may need. The digital technologies allow for transcending time and space by being available in an asynchronous mode. On top of all that, everything including communication, evaluation, feedback, and course content are available in a one-stop-shop for the learner.

The essay and the Tech Talk by Ted Nelson brought this dichotomy of teaching technology supports into bold relief. After reading the essay, I was left with a few questions with respect to what his vision of transclusion-based hypertext would look like and function. After watching the video, the concept became much clearer to me. Being able to watch him present engaged one at the start, increasing connection to the presenter and presentation. His language choice, non-verbal cues, and use of pace, provided an experience that transcended a mainly oral delivery. The use of very fundamental visual aids enhanced the message, laying clear what his main message was. The multiple modes used were not extravagant, but they were highly efficient in supporting the text that he was presenting.

Contrary to “Bolter and Kress that we are witnessing a decline in textual modes of representation due to a rise of visual modes of representation” (ETEC 540 66B>Pages>Idea Processors and the Birth of Hypertext), my contention is that we are increasing and enhancing textual representation in new and ever more supportive means. In his blog post, How Much Data Is Created on the Internet Each Day?, Jeff Schultz illustrates the mind boggling amount of data produced in the digital sphere. While much is what we would not consider true text or the representation of it, are these not just replacements or enhancements of previous technologies, but with more permanence? How many of the notes passed in classerooms from the 1970s were kept? Now there is the ability to keep all of them if one so chooses. Snapchat essentially replaces the old mode of message delivery but now there is the ability to save it permanently if one desires. Instead of just text and maybe a hastily drawn picture, photos, emojis, and other digital modes augment the message. Short messages containing video and photos being passed through applications such as Instagram are just replacing technology such as the telephone party line or gathering at the general store to get the latest local news. True, much of the data uploaded is not what could be considered as advancing academic discourse, but these in most cases are just reimaging modes of communication. There is still impetus to produce academic works, but now one’s reach is global if one chooses. By being able to touch so many others, the discourse can be extended, enhanced, and used to benefit greater numbers. Textual modes of representation are not being replaced, they are being enhanced. Could we consider this the second age of enlightenment?

References:

Nelson, Theodore. (1999). “Xanalogical structure, needed now more than ever: Parallel documents, deep links to content, deep versioning and deep re-use.” Available:

http://www.cs.brown.edu/memex/ACM_HypertextTestbed/papers/60.html (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.

Nelson, Ted. “Transclusion: Fixing Electronic Literature.” YouTube, Google Tech Talks, 8 Oct. 2007, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9kAW8qeays&feature=youtu.be.

Schultz, Jeff. “How Much Data Is Created on the Internet Each Day?” Micro Focus Blog, 10 Oct. 2017, blog.microfocus.com/how-much-data-is-created-on-the-internet-each-day/.

Images:

A.B. Dick Model 217G Spirit Duplicator. Flickr, Yahoo!, 30 Dec. 2011, retrieved from www.flickr.com/photos/41356722@N06/6597673139.

michael yates

July 15, 2018 — 12:19 am

This post hit pretty close to home for me, especially your recount of your first teaching experience in 1991! It is so close to my CURRENT teaching position overseas.

Now Ted Nelson was one of the first people to put a name to hypertext, and I thank you for bring this Tech Talk to my attention. I had never thought about how computing has been made to imitate paper and sell printers! But if you look at it (especially in the 2000’s) that is pretty much what it was like. Do something on the computer, then print it out and share it (Fax machines / Couriers) with who needed it.

Now I wonder if it is still currently like that, printed material is a thing of the past (in my opinion as well), it is simply not all that useful when things change so quickly. But do you think Nelson’s vision is coming true? (11 years after his Tech Talk?). Text has taken such an amazing turn in the online collaborative space. We no longer fax paper copies of documents to people, we simply create them online and share a link, put them on a cloud or email the document.

His Xanadu (I think that is what is was) could easily be reproduced, and most Library based systems can do what he was proposing (maybe not as seamless, but you can almost always find the context of document by following a link). I think there needs to be an evolution of the PDF document, even though you can incorporate links, it is still rather static.

Again, great post!

Carri-Ann Scott

July 19, 2018 — 8:46 am

Hi, Michael.

Thank you for such an engaging post. I too remember the days of the spirit duplicator. I think I left a few brain cells in the “copying room” from the inhalation. Who says education can’t be fun 😉

I look at the freedom from the bonds of paper (very good pun, by the way) from a slightly different perspective.

You see, while many of our colleagues work in a world where their students are literate, mine are not. At least not when they first step through my door. My students come to me at three-and-a-half years old. My instructional delivery methods can never be paper-based. These tiny humans simply cannot read, or cannot read well enough to follow written instruction. Therefore, my challenge has always been how to deliver meaningful, differentiated instruction to students, each of whom will absorb that information differently.

This ties in directly with your comment that, which contradicts Bolter, that we are creating text in increasingly diverse means.

Instead of grabbing pen and paper to document their learning, the children in my class might use an iPad and the program “SeeSaw” to take a picture of their learning and then either record a voiceover explanation or annotate the pic with letters, words and scribbles – depending on their current cognitive level.

This type of creation would have been unimaginable 10 years ago. I have 4 and 5-year-old students who will dictate an entire story to “Siri” and revel in how their words appear on the iPad, which they can then print out (a step that gives tangibility to their learning, just as the first book for any author would). These stories go far past the “See Jane run” mini-sentences of my first years of teaching. The amount of creativity and problem solving is inspiring! In many cases, they are learning to read by looking at text they have created, not boring pattern-based texts that I have traditionally used to teach literacy. They are learning to correct their work, as Siri inevitably errs when transcribing the lisp of a 4-year-old. And they are learning that the lack of any physical skill (fine motor control, in this case) does not limit the output of creative work they can produce.

Do I use paper? Of course. The friction of pencil and paper is a sensory experience that contributes to the development of writing skills. But paper is definitely being replaced, if slowly, in my classroom.

My wonder lies in the implications for future generations. While I still content to my 11-year-old that she must learn to print neatly and spell correctly, with pen and paper, her world will be completely different in design and expectations from that in which we grew up. How long before the act of pencil and paper creation, and the fine motor skills required to support it, are no longer taught in school? Will we see it before we retire? Sooner? Or will it always be a part of the academic world?