Indigenous Futurism: Reimagining “Reality” to Inspire an Indigenous Future

![Image: Wendy Redstar via [gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures]](https://blogs.ubc.ca/fnis401fwikler/files/2016/11/Screen-Shot-2016-11-25-at-10.57.21-PM-300x253.png)

Image: Wendy Redstar via [gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures]

To begin, I chose to represent the following knowledge related to Indigenous Futurism by titling this blog post, ‘Indigenous Futurism: Reimagining “Reality” to inspire an Indigenous Future’. I chose this title to reflect the dynamism of Indigenous futurism and highlight the role of IF not only in reimagining a future with Indigenous peoples, but also its ability to recreate lived, past events or reality. The understanding of the past being perceived as realistic by western definition just because it happened, is a constricting way of thought. IF allows for Indigenous peoples to reclaim these events through a technological space and offer a contrasting narrative to the colonial perspective of the past, present and future.

While screen sovereignty encapsulates a thoroughly Indigenous production process, assertion of authority over the narrative and the prioritization of an Indigenous audience to address critical issues, Indigenous futurism allows for a complete reimagining. Indigenous Futurism expands this form of sovereignty by reimagining contexts in which Indigenous issues, cultures, traditions and livelihoods have another life form, in the past, present and future. The medium and message of knowledge and events pertaining to Indigenous peoples have and continue to be largely misconstrued by mainstream media outlets, favouring a colonially oppressive narrative. Indigenous futurism allows for “…Everyday Indigenous peoples to restore their beings, bodies, genders, sexualities and reproductive lives from colonial institutions… projecting decolonial love and kinship into the cosmos” [Lindsay Nixon] Lindsay Nixon continues to highlight the benefits of this thought form stating, “…Indigenous peoples are using our own technological traditions, our world views, languages, stories, and our kinship as guiding principles in imagining possible futures for ourselves and our communities”

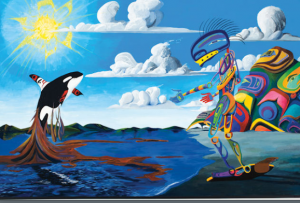

We Must Protect the Land for the Next Seven Generations (2016)

digital print and beadwork on canvas: Chief Lady Bird (Nancy King)

“…In knowing the histories of our relations and of this land, we find the knowledge to recreate all that our worlds would’ve been if not for the interruption of colonization.” [Erica Lee]

“Armed with spirit and the teachings of our ancestors, all our relations behind us, we are living the Indigenous future. We are the descendants of a future imaginary that has already passed; the outcome of the intentions, resistance and survivance of our ancestors. Simultaneously in the future and the past, we are living in the ‘dystopian now’.” [Molly Swain podcast Metis in Space]

Indigenous Futurism as a Tool Against Colonialism

X

The very essence of Indigenous futurism threatens the longevity of white supremacy and colonialism. The imagining of an existence without colonizers attempting to snuff out Indigenous cultures, traditions and livelihoods is a threatening imagining to behold for oppressive regimes . Indigenous peoples and livelihoods are typically imagined to death imaginary which Andrea Smith writes is the perception of “Indigenous peoples as always disappearing in order to legitimize settler occupation of the Canadian state.” With this understanding, Indigenous futurism is an integral component to revitalization and survival of Indigenous cultures, livelihoods and traditions. Jolene Rickard draws attention to this problem of colonial perception, writing, “…Ironically image of natives is still firmly planted in the past… the idea of natives on frontier technology is inconsistent with the dominant image of ‘traditional Indians’.”[Jolene Rickard, First Nation Territory in cyber space declared: no treaties needed]

MOONSHOT: The Indigenous Comics Collection

Indigenous Futurisms also confront the artificial perception of Indigenous cultures, and traditions promoted by colonial regimes in the reimagining of art and artistic spaces. Colonial regimes prefer to paint Indigenous peoples and cultures as a thing of the past with no place in the present or future to facilitate the idea that assimilation for Indigenous peoples is inevitable. Art and creative spaces are the perfect medium for recreating and imagining Indigenous identity, cultures and traditions. Indigenous artists are often discredited from creating authentic Indigenous art if it doesn’t incorporate solely traditional styles.

Image of Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun found via MOA online.

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, an artist who utilizes IF to reimagine the future and past events, is the perfect example of the power of IF in artistic spaces. Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun is a Canadian First Nations artist. “His paintings use elements of First Nations imagery and surrealism, and explore issues such as environmentalism, land ownership, and Canada’s treatment of First Nations peoples” Accused of not creating authentic Indigenous art for lack of sticking with traditional First Nations paint colors, (red black and white) Paul challenges colonial perspectives through IF.

“A lot of my work deals with the colonial occupation native people have had to endure… that is what my work is doing recording history… I am a modernist, who is dealing with modern issues of modern times. I have to go to the past to talk about the future because when you are so busy being oppressed you have very little time to deal with history.” Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun

An Indian Game (Juggling the Books), 1996. Acrylic on canvas. (Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery)

An Indian Game incorporates modernistic colors in traditional First Nations symbolism and imagery- we know the figure is a native man because of his traditional markings but a man in an imagined future with modern colors revealing his identity. The small space, another indigenous symbol, he is running on represents the unliveably small size of land Indigenous peoples were subjected to live upon with reservations. The mountains and land features are portrayed with vibrant native imagery and symbolism but the native man cannot access them, confined to the small track he is running on. Paul could be representing the past, future or present with this painting.

Karen Duffek on how people view Pauls’ artwork, “…There’s a common tendency to look at historical Indigenous collections as somehow timeless. But when Lawrence’s paintings refer to legislation that has affected Indigenous people, such as the Indian Act and anti-potlatch legislation, it’s the same period of history as when the museum’s collections were made.”

The way in which Lawrence Paul’s exhibit reimagined a museum space at MOA to redirect the narrative surrounding critical issues affecting Indigenous peoples extended beyond viewing modern paintings. Paul incorporated a futuristic interactive experience at the end of the exhibit where guests are invited to rename the province of British Columbia through a technological platform. Duffek explains the futuristic strategy behind this interactive experience saying, “…It positions us to think about the future, and to think about what it would look like if we renamed this province in a way that acknowledges that colonial history and acknowledges the place we’re in today.” This is a powerful example of physically reimagining spaces through Indigenous Futurism.

Museum of Anthropology: Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Killer Whale Has a Vision and Comes to Talk to me about Proximological Encroachments of Civilizations in the Oceans, oil on canvas, 2010.

Skawennati and Indigenous Futurism through Technological and Virtual Mediums

X

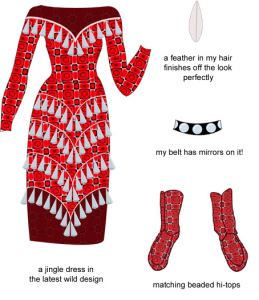

Skawennati, a Mohawk multimedia artist facilitates Indigenous Futurism through technological platforms and machinima, resisting colonial narratives of critical events for Indigenous peoples. In 2001 for a millennium piece, Skawennati worked on imagining Indians in 25th century, through a paper doll web based time travel journal. The timeline began in 1490 ending in 2490, with the character time traveling to different events, one event per century, writing in her journal following each event. The reflection provides the audience with an opportunity to imagine and experience perspective as a modern Indigenous woman. The time traveler visits powwows of the future and critical historical events. Skawennati revealed this was the first time she imagined native people in the future, articulating the importance of Indigenous peoples being imagined, and imagining themselves in the future.

Skawennati’s Paper doll time traveller’s outfit via imaginingindians.net

Further, Skawennati uses Second Life, an online world, that is user created to implement machinima, making videos in a virtual environment. She created time traveller with curated mini episodes through Time Traveller TM, building a virtual community platform to engage with historic events through an Indigenous lense as well as imaging a resilient Indigenous future. Skawennati’s main intent was to create a site to integrate more native art on web based platforms while simultaneously reconfiguring the ‘Indian space’.

Screen grab from Time Traveller episode 3 mohawk crisis 1990