A ‘Flip Through’ of The Unnatural and Accidental Women: a play by Marie Clements

[A detailed guide to a deeper understanding of our Flip Book, reimagining Clement’s play]

“I see you, and I like what I see.”

“I see you—and don’t worry, you’re not white.”

“I’m pretty sure I’m white. I’m English.”

“White is blindness—it has nothing to do with the colour of your skin.”

(Clements, The Unnatural and Accidental Women 82)

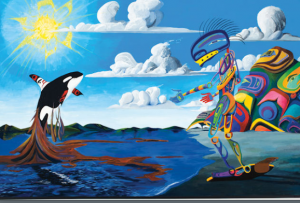

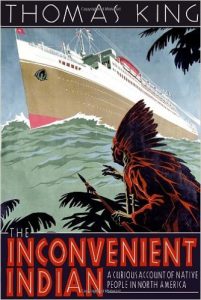

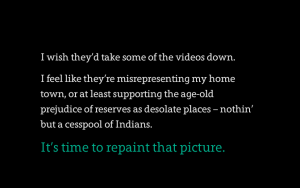

“The Unnatural and Accidental Women” reimagines the murders of 10 middle-aged Native women by a serial killer in Vancouver during the 1980s. Clement’s titling of the play draws attention to the problematic reporting of the Native women’s deaths- the coroner’s reports found the deaths “unnatural and accidental”. A dramatization play, The Unnatural and Accidental Women was written by Vancouver playwright Marie Clements and performed in, among other places, Buddies in Bad Time Theatre in Toronto (2004). In the play, the writer focused on the story of the victims in an attempt to redress the failure of the news media to do so. Clements confronts the complacent depiction of missing and murdered Aboriginal women by highlighting racist stereotypes and profiling of Indigenous women that perpetuates violence against Native women. The play asserts an important call for social action with the reimagining of the Downtown East Side (DTES) largely portrayed as an uninhabited wasteland, dehumanizing the Native and non-native women living in the poorest region of the city.

This flip book serves as a visually engaging experience for the reader to delve deeper into the themes of violence against women, colonization and gentrification Clements unravels throughout the play. As you navigate through the pages of the flip book, you will notice various hashtags drawing attention social, political and humanitarian issues. Indigenous peoples ways of life and existence are inaccurately confined to relics of the past to convenience the colonial narrative. Effectively engaging with various social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook and Instagram) enable messages independent of colonial influence to be conveyed through differing mediums, connecting to a wider audience and redirecting the narrative. The use of hashtags have become vital forms of communication reimagining how people engage across various mediums. The hashtags implemented throughout the flip book connect to news and protests or marches related to indigenous issues. For example, hashtags relate to the annual march for missing and murdered Aboriginal women February 14th in the Downtown East Side. All sounds for this project were recorded on foot in the DTES, unless otherwise stated.

I. Setting the Scene

Sounds you are hearing, “…A collage of trees whispering in the wind… the sound of a tree opening up to a split. A loud crack—a haunting gasp for the air that is suspended” (9)”

To enhance the interactive experience of the flip book for the reader, there are various sound bytes included on each page. Sounds are critical to ensuring a fully immersive learning experience of important events, messages, or other traditional knowledge systems. As seen with the podplay, ‘Ashes on the Water’, “…An invitation into a sensory landscape of words, movement, breath and song” sounds enhance sensory experiences and empathetic abilities for the audience. The podplay is linked on the cover page of the flip book to connect the importance of sound descriptors and sound effects in creating innovative mediums for Indigenous story telling and knowledge sharing. Also, fun-fact boxes link to relevant current indigenous issues

“In many cases, when references to the tides, trees or traplines appear in her play, they are often surrounded by the static of a faulty telephone connection, or the ebbing and flowing of entirely different scenes. In doing this, I feel as though Clements is cleverly making reference to Canada’s tendency to wash over a robust history of environmental plunder and racism.” – Erin Wunker

Throughout the play, Clement sets the scene with sound descriptors. You will find in the flip book, we have incorporated the sound bytes accordingly. The excerpt above describes the sounds of trees falling in the forest, you will find this sound and others linked in the flip book to assist in the creative, immersive reimagining of the play script.

“Clements weaves the city with the forest, suggesting not simply that women are aligned with the earth, but rather that the viewers should correlate the felling of trees with the bodily violence of the women’s deaths.”

Page 4:

On the fourth page of the flip book, “Keep on walking… down Hastings Street” you will read an excerpt from the script of Rebecca’s thoughts as she is walking down Hastings street. The sound byte leads you to a recorded sound clip from Hastings Street- you hear muddled conversation and city sounds while reading Rebecca’s thoughts. You feel like you are walking alongside her. A “HELP” sign advertised in the window to a passerby may read simply as a need for employees whereas for Rebecca, it triggers thoughts and emotions she is experiencing whilst searching for traces of her missing mother. Various interpretations for the message conveyed through this medium of a help sign advertised in the window are brought to attention on this page of the flip book.

Page 5:

The fifth page of the flip book details the scene from the script of Marilyn sitting in the Barber’s chair. The reader is hyper aware of her fate as she engages with the killer. She is alone with him. The page includes a photo of an alley in the DTES with the hashtag #AmINext? A hashtag that went viral bringing awareness to the crisis of missing and murdered aboriginal women. Included on this page is a link to a sound byte of sounds heard while sitting in the alley. Little to no conversation is heard. The sound illicit a feeling of desolation.

Page 6:

The sixth page of the flip book, ‘The Barbershop Quartet 2’ includes an excerpt from the script detailing the Barber’s prowess to killing Indigenous women with alcohol poisoning. On this page, the sound link allows the reader to hear the Barber’s laughter (sound clip from the DVD version of the play).

Page 7:

The seventh page of the flip book, ‘The Barbershop Quartet 3’ recounts the scene of Penny trying to escape with help from the ghosts or spirits of the deceased Indigenous women killed by the Barber. Throughout these scenes, the women’s braids are chopped off prior to their murder- symbolizing the defamation of their Indigeneity by the Barber. The purple globe icon in the bottom right corner links to a news article reporting the grizzly killings by the Barber and his release from jail. The sound clip links to an excerpt from the play – you hear a woman explaining ‘he sees himself as the hunter and you as the animal’. The inclusion of this sound clip emphasizes the dehumanizing effect the crisis of missing and murdered Aboriginal women has had upon Indigenous peoples.

Page 8:

A photo clipping from a newspaper detailing the gruesome killings of the Indigenous women. Hashtag #NationalInquiryNow to emphasize a call to social action to pressure the Canadian government to launch a national inquiry into the crisis of missing and murdered Aboriginal women. The lack of appropriate media coverage and attention by the Canadian government is an intentional ‘white out’ of critical information reflecting the violent racism towards Indigenous peoples.

“We need #justice for over more than 1200 missing #Aboriginal women

The Soundcloud icon allows the reader to listen to the sound scissors cutting hair. This sound is important to setting the scene, albeit a bit gruesomely, the sound presumably prelude the killings of the Indigenous women.

On this page, we include an excerpt from the script of Aunt Shadie leading the women in song, beneath the coroner reports of the three murdered women to confront the dehumanizing narratives and identities that are problematic with mainstream media reporting of missing and murdered Indigenous women. The introduction of song positions the women to a role of empowerment, using language and ritual as they ‘gather their voices’ to grow in strength.

Page 9:

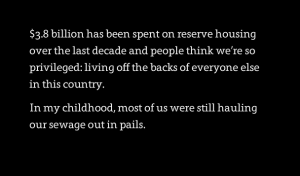

Clifton Hotel- Vancouver. Low income housing

‘Room #23, when you’re 33- Clifton Hotel’, this page draws attention to the problem of displacement that is exacerbating violence against Indigenous women. The purple globe icon on the right side of the page links to a news article on protests surrounding gentrification in the DTES. The twitter icon at the bottom right corner of the page links to the official account of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Displacement and destruction of the land threaten the survival of cultures, traditions and Indigenous knowledge systems that are essential to revitalizing community dynamics and a stronger sense of self to assist in the prevention of Indigenous women vulnerability to violence. The hashtag #StolenSisters positions Indigenous womanhood in a prevalent, modern medium.

The sound clip allows readers to listen to a scene from the play where the man from the dresser, which we can interpret as western societal judgement, degradingly identifying the Indigenous woman as ‘Pocahontas’. The mirror of THE DRESSER starts to reflect a man’s face” verbal degradation, repositioning the Indigenous woman to be seeking approval from an inanimate object or as it is revealed towards the end of the scene, a man.

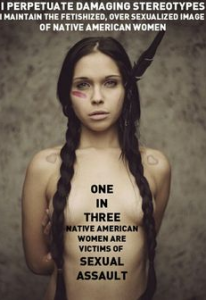

This page is incredibly symbolic of the stereotype and pressure Indigenous women experience by mainstream, westernized society. Indigenous women’s bodies are sexualized, their spirit belittled to objectification of an exotic ‘animal’ (Clements plays on the theme of hunter vs. animal with the barber). This objectification of Indigenous women not only makes them vulnerable and susceptible to violence, as seen with Clement’s recount of true events, but also inhibits the level of reporting dedicated to the crisis of missing and murdered Aboriginal women. The crisis of missing and murdered Aboriginal women throughout Canada exemplifies the incredible opportunity exploring alternative technological mediums provides in garnering global attention when the Canadian government and news outlets cannot be relied upon for accurate and thorough coverage these issues deserve.

Page 10-11:

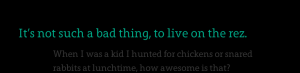

“Drole de Squaw,” an example of the hyper-sexual images of Indigenous. “

The Dresser attacks the woman, or western and colonial conceptions of Indigenous women, ending her life. A sound clip allows the reader to hear an ambulance recorded driving along hastings street on the DTES. An image of a dresser taken from my bedroom. The engagement with the dresser is also symbolic- this is where people go to retroactively change their appearance by dressing in different clothing that day. The cause of violence the character experiences in the book is reflected in this scene with the emphasis of perception of image and identity upon Indigenous women.

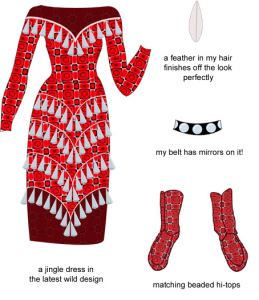

the sound clip leads the reader to a recording of women singing through the use of song (a clip recorded from the movie version of clement’s play) the strength, resilience and community of Indigenous women are remphasized and revitalized. colonization upon first nations peoples by the canadian government directly targets indigenous women. traditionally among first nation communities, indigenous women are the nucleus of community dynamics- knowledge holders and sharers, women are deeply respected and valued among first nations peoples. although the women singing were murdered by the barber, Clement depicts them as singing in unison, a unifying and empowering moment repositioning the narrative and deflecting the identity as victims and rather embracing an identity as strong, indigenous women. Hashtag created, #HelloMyNameisWhoCares

Page 12:

‘The Empress’. Clement’s use of spirits and ghost imagining for the murdered women repositions victims in a place of strength, having another opportunity to control and influence destiny. The sound clip the reader will hear on this page is Granville strip at night time, creating the sensory experience of Rebecca meeting the Barber at the bar. “…Learning to speak with ghosts ruptures the stable image of the socio-cultural semiotic archive and subverts the linguistic hegemony that inscribes gender and regulates bodies”[https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/18433/19925]

Hashtag used, #StoptheViolence

Page 13-14:

From “Apache Chronicle,” Lynnette Haozous as Lozen, the famed Chircahua Apache woman warrior who rode and fought with Geronimo’s band of renegades.

Clement’s reimagines the outcome for the murderous Barber with Rebecca discovering his true identity and ending his life. Hashtag created, #Justice. The sound clip is of Aunt Shadie from the play telling Rebecca how the Barber behaves as a hunter does to an animal. This scene signifies the importance and resilience of Indigenous women in protecting one another and sharing knowledge. The women are reunited and restored to their natural state it seems, with their hair flowing, no longer in possession of the Barber. In the end, Rebecca became the hunter not the animal.

Page 15:

#StartHealing and the end of the Barber ends our flip book. Shown is the Survivors totem pole in Pigeon Park; a pole that represents healing, reconciliation, and justice that is still needed. It also honours survivors of the DTES and issues commonly faced, including gentrification, colonization, racism, and poverty (CBC News, November 5, 2016). Songs were sung after the raising, just a song was sung after the Barber was finally killed. Themes of sadness, but also strength and the beginning of a healing journey are linked to these two images.

Pawson, Chad (2016/11/05). “Survivors Totem Pole Raised in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.” CBC News. Retrieved from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/survivors-totem-pole-vancouver-downtown-eastside-1.3838801

IV. CLOSING

Hundreds march in Victoria, Vancouver for missing and murdered women

We chose to depict the closing scene of the play with imagery of womanhood, and a sense of a tight knit community, reflecting Clement’s sense of community in the play with the murdered women joining together to support Rebecca. This message of strength among Indigenous women is a message often left out of mainstream media platforms and news reporting, facilitating the victimization of Indigenous women. As you interact with the last couple of slides in the Flip Book you see two scenes: a scene from the play of the murdered women coming together and second, women marching together to raise awareness for the Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women. A sound clip encases the listener with the sounds of women talking, connecting and supporting each other. n Clement’s other works, she challenges how Aboriginal women are typically marginalized by showcasing their perspectives as a way to reclaim the screen and portray what really happened, something the media has failed to do. The goal is to reflect the realities of Aboriginal women as strong loving leaders and knowledge keepers, allow viewers to rethink their beliefs, and trigger new conversations through visual sovereignty and thinking outside of the box. The goal of this project is to reflect the realities of Aboriginal women as strong loving leaders and knowledge keepers whilst allowing viewers or readers to rethink their beliefs, and trigger new conversations through visual sovereignty and new communicative mediums.

“Any preconceived expectations are put off—the women, though decidedly victims of their status and situation are not powerless. The killer is not merely a racist misogynist but a fleshly manifestation of human emotion…Clements refuses the impulse to characterize the women as victims of race, sex, and consequence.”

– Erin Wunker, Dalhousie University [https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/18433/19925]

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/18433/19925

![Image: Wendy Redstar via [gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures]](https://blogs.ubc.ca/fnis401fwikler/files/2016/11/Screen-Shot-2016-11-25-at-10.57.21-PM-300x253.png)