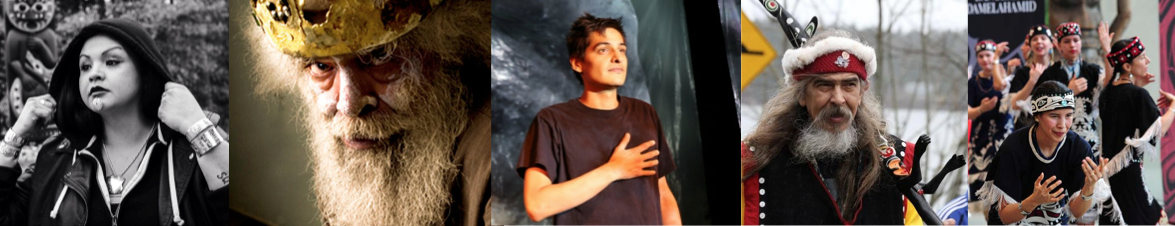

A bit about Dana Claxton from her opening of Made To Be Ready:

Dana Claxton is a Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux performance artist, photographer, and filmmaker from the Wood Mountain reserve in Southwest Saskatchewan. Through her practice which she situates within a contemporary art framework, she critiques the representation of Indigenous people within Western anthropology, art, and entertainment. In particular, she is interested in exploring notions of Indigenous womanhood, beauty, and sovereignty. During her remarks at the opening of her exhibition Made To Be Ready at SFU Audain Gallery, she acknowledged the Coast Salish peoples for having shared their knowledge of the land with her and for the welcoming she has received from them to have pursued her practice here for over 30 years. She thanked the woman who has been working with her for over 25 years as the performer who often appears in her film and photographic work, as well as curator Amy Kazymerchyk for working closely alongside her with this exhibition.

read her exhibition statement here

Uplifting, 2015, digital video

In particular, I discussed my experience of her film performance Uplifting, which I found to have had quite a resonating effect for me through the motions made by the Indigenous woman performing in it. The film was set up next to the entrance of the gallery and featured a spotlight cutting across the screen horizontally in the center. A woman dressed in a red jumpsuit appeared from the left side, slowly crawling in on her hands and knees. She moved in a pattern of putting her left hand down, then pulling her right knee forward, lifting up her right hand and placing it down on the ground, followed by her left leg dragging in from behind. The whole time she moved, she appeared to be struggling and in pain, but she seemed empowered by a determination to keep going despite her weakness. Her movement can be related to Karyn Recollet’s notion of the ‘in between spaces’ and ‘Indigenous Motion’ that she describes in our readings “For Sisters” and “Dancing ‘Between the Break Beats’: Contemporary Indigenous Thought and Cultural Expression Through Hip-Hop”, of which she states as spaces that are “linked to an impulse that forms the base of all movement and creation” as a way to release the weight of colonialism felt within one’s body (420). The slow pauses of the woman picking her body back up into motion between her sudden dropping of hands and legs back onto the ground as she completes each step seems to illustrate this idea.

As the woman reached the end of the right side of the screen, she collapsed down from her hand and knees onto her stomach, rolling over on her side into a fetal position. She turned over onto her back, breathing heavily, and started tugging at the red jumpsuit material on her chest. Her pulling of the fabric became more aggressive, acting as a moment of climax within the performance, until she suddenly was able to use this force to sit right up into a V-shape position with her legs pointing outwards. She paused to catch her breath, and then slowly starts pulling out a cultural belonging that appeared to be a neck piece of a fringed pouch out of her chest. She slowly rolled up to stand with the neck piece, until she became grounded in her stance as she raised it above her head. This journey the woman undertook and her moment of overcoming her struggle seems to further illustrate Recollet’s explanation of ‘Indigenous motion’, which she views as the idea that there are portals into other worlds where one can connect with to undergo a transformation of self-identity (418).

Dirt Worshipper, 2015

As another performance example of Claxton’s work apart from her Made To Be Ready exhibition, I introduced Dirt Worshipper, a live performance I got to see at the Slippery Terms faculty exhibition held at the AHVA Gallery on campus last September 2015. In this work, Claxton performed repetitive actions of ripping the fabric of a large printed sign that read ‘Dirt Worshipper’ in bold purple letters with a vibrant teal background up on the wall at the back of the gallery. She progressed in a linear direction from left to right, ripping a strip of the fabric in intervals of eight with her hands. It made a tearing sound that seems to resonate as another form of pulsation with the ‘in between beats’ that Recollet discussed taking place. In keep with her practice, this work was an act of engaging with cultural racism and the releasing of terms such as ‘Dirt Worshipper’ that have been imposed as stereotypes onto Indigenous peoples.

Thinking about digital media, performance, and cultural belongings:

How might the use of mediation in Claxton’s exhibition through the projected video, illuminated lightboxes, and theatrical lighting in the exhibition space extend or diminish the performativity and liveliness of the cultural belongings? Since this was not a live performance, how might this alter or affect our experience of the cultural belongings as a ‘lived force’?

Vanessa,

I enjoyed reading your descriptive accounts of Dana Claxton’s video and performance pieces. Your usage of terminology when it comes to movement and visual culture really helps us to imagine how witnessing “Uplifting” and “Dirt Worshipper” must have been.

Your questions are provocative, and I also find myself wondering: How may the meaning and/or emotional effects of “Uplifting” have changed were it a live performance?

Hi Eliana, thank you very much for sharing your thoughtful remarks and meaningful comments about my post. I think your question is something very important to consider and recently I have been reflecting much on live performance in relation to its documentation. In the field of performance studies (specifically within an art context), there are so many different theoretical perceptions as to whether the documentation allows the ontology of a performance to live on or whether the documentation alters the actual moment (time and space) the performance originally took place in to become something entirely different. I’m realizing now that between Dana’s “Dirt Worshipper” and “Uplifting”, there are different aspects that allows one to work well as a live performance and the other as a documented performance. With “Dirt Worshipper”, I find it is more about the repetition of Dana’s action of ripping since there is no narrative, which gains more of a presence for us with her performing it live versus watching it on a screen. That moment of ripping the fabric can only happen once, it can’t be undone. The trace of this action, or its documentation, then becomes embedded within the ripped material itself, in this case as a destructive rupture of breaking apart this stereotype (or at least that’s how I interpret it).

In comparison with “Uplifting”, I think that its performance as a narrative in which the Indigenous woman’s repetitive crawling movements progresses into a release of her struggle through pulling out her cultural belonging allows for it to work as a documented performance that replays in an endless loop. However, I feel that you have a strong point in your question that its meaning and emotional effects would be different or altered if we were to witness it live. I think that having it performed live would have a more profound emotional impact and allow us to connect with her on a deeper level since her actual body would be moving amongst us in the same time and space. It really depends on how the performance is enacted as a live one though. If the audience is positioned to stand up looking down at her (standing often happens in a gallery space), we would loose viewing her movements from the side-view that the screen provides, thus contributing to an ‘othering’ between the viewers and her. If we are all sitting to watch her, then that might be a more reasonable means of allowing us to connect with the feelings of pain and determination she is undergoing. But then it becomes more about that one particular moment of the woman’s release, which might change the context behind as to why Dana chose to have it in a loop in the first place: to re-enact her story as a constant struggle, something that requires continuous effort and willingness from all of us to resolve.

So, there are benefits and drawbacks between the live and documented ways of experiencing any performance. Most important is that the artist makes their choices based on what they think would most effectively allow their main intentions to resonate amongst their viewers. Thinking about all this, it would be interesting to also consider how Indigenous performing artists might work with ways of embedding traces of a live performance within the actual materiality of cultural belongings, so that the performance’s ‘ontology’ lives on through another means.

Hi Vanessa!

I loved your vivid description of the performance; it really allowed me to visualize the experience well.

With respect to your touching on viewing recorded performance as opposed to witnessing it live, I feel much of the power of the piece may be lost. Although in the particular case you described, I feel like the loop is almost a reminder for the viewer that the struggle (like the process of decolonization) is purposeful, and can culminate in release, but is also ongoing.

I also had the experience of viewing that “Dirt Worshipper” piece, after it had been torn, and felt like I missed key context for it. Having your description of the opening to replace that lost context was really valuable.

Your post has sparked interesting conversations about the “liveness” of performance and the life that performance takes on when it is captured in forms that can be replayed! I agree with both Melissa and Eliana, your descriptions of the work are excellent as well as your use of Recollect’s work to theorize it.

Like Eliana, I also wonder if the affect of Claxton’s performance would have been different if it was live. There were quite a few people who attended the exhibition opening that were expecting a performance. Unfortunately the expectation to perform can’t haunt the work of both performance artists and performing artists. My husband and I have been asked to perform quite often when we were expecting just to attend an event. I imagine the pressure or presumption must be much greater when it’s your own show.

Thank you for your lovely and thoughtful comments Melissa and Dr. Dangeli. I feel that after watching Dana Claxton perform live today as part of the Cutting Copper symposium, I agree with your points on how the “liveness” of performance can leave behind a feeling that has a more powerful resonance over witnessing a recorded performance. I think there is a difference in how we come to witness documented performances over live, and that difference lies in feeling that you are actually part of it; part of the bigger picture the performance is speaking to when it is happening live, and that you’re experiencing it together amongst many bodies.

Dr. Dangeli, I’m curious about the distinction you have made between performance artists and performing artists. I know in class you have brought up the question as to whether dancers who dance as part of traditional and ceremonial work should be thought of as ‘performance artists’. I think this is an interesting and important point to bring up as we examine these various ways and purposes of performance in our course.

As a performance artist myself, I think that there is pressure to some extent in knowing that you are going to be performing live. For me, though, as long as I have gotten to a point after much thinking where I feel comfortable with the decisions I have made in terms of how I will be articulating my performance through my actions, I find myself feeling safe to be embraced by being in this vulnerable and precarious position of performing. That is interesting Dr. Dangeli that you and your husband are asked to perform unexpectedly often. As I’ve experienced so far, I find that this normally isn’t the case for performance artists, especially if it’s performed in a gallery. I can only imagine that that would also put some pressure on to perform too.

As stated above, you did a great job explaining the event. Although I did not attend, I feel as though I can imagine what was taking place from your description. The role of Indigenous new media is a topic that I find intriguing and important. I wonder how we might think about the role of media in relation to cultural belongings. Indigenous people are using film as a way to represent their experiences, stories, histories, and identities. In this sense, can the film itself be considered a cultural belonging?