On January 17 2016, I attended a performance at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The performers were the Rainbow Creek Dancers (Haida), led by Robert Davidson. The group is named after a creek that runs behind Masset, Haida Gwaii and was founded 1980 by Robert and Reg Davidson. In addition to founding and leading the Rainbow Creek Dancers, Robert Davidson is a highly acclaimed visual artist who produces the dance group’s regalia and masks. His art has been exhibited in many public and private exhibitions and he became a master carver at an early age.

Before the performance began, Musqueam elder Debra Sparrow welcomed the performers and the audience to her territory and discussed. She briefly touched on the ancestral and historical connection to the Vancouver city space, and stated: “the city of glass was once a city of forest”.

Following Sparrow’s words, one of the museum curators introduced Robert Davidson as a visual artist, detailing the collection of masks that reside in the Vancouver Art Gallery itself, that would be danced to life throughout the performance. After finishing her introduction the Rainbow Creek dancers entered and Robert Davidson made his introduction. He began by giving thanks to the Musqueam, and then proceeded to explain that the performance would be a fusion of both traditional and newly choreographed or altered traditional songs and dances. He then announced the healing song and contextualized it’s need – to heal the traumas of colonialism. Following this sombre performance the group went on to perform a series of dances, each introduced by Davidson. The context of the dance, what the dance was depicting, whether the song and choreography was new or had been passed down for generation, was all re-stated at the beginning of every number. As Dr. Dangeli pointed out in lecture, Davidson’s recurring introductions to performance pieces were not meant to be a translation but an oral history, a strategy to situate Haida culture in the past and present.

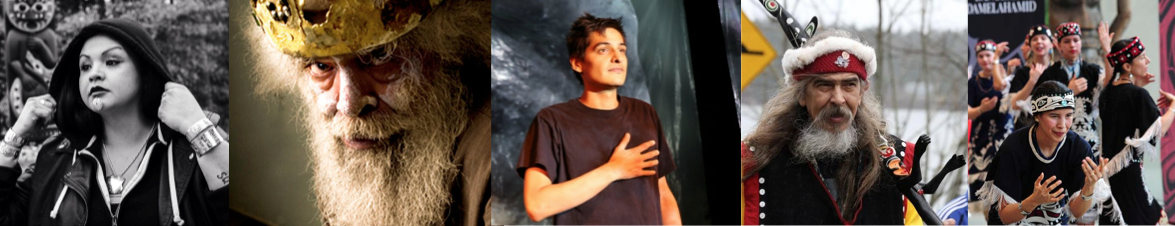

There were a few aspects of the Rainbow Creek Dancer’s performance that I especially took note of. Firstly, the majority of their dancers involved them depicting animals that had specific cultural significance and meaning. Secondly, every member of the dance group played a role in every single song. Whether that would be to hold a sheet of fabric to camouflage dancers, drumming, singing or dancing – the performance was the result of a collective effort and all members contributed to the final product. Another notable aspect of the performance was the large age range of the dance group, from elders to toddlers, a community formed on stage that truly emphasized kinship and teaching, or more specifically, the passing on of tradition.

Watching the Rainbow Creek Dancers I began to reconceptualize what it means to be ‘professional’. Though many interruptions (such as a child crying and running off stage) took place throughout the performance and a relaxed atmosphere was seemingly encouraged, the performance group was undoubtedly professional and were clearly extremely practiced and poised, able to share themselves and their culture with immense feeling and precision. Throughout the performance I began to understand how conceptions of professionalism are incredibly linked to victorian colonial standards and how the Rainbow Creek Dancers exemplify what decolonial professionalism can look like.

Madison, I really like one of your comments about “every member of the dance group played a role in every single song”. I was involved with musical theatres groups throughout my life, and if you could not sing or dance, you would definitely not have had a role on the stage. Incorporating every member really shows that the priority is about making community (as Nolan talks a lot about with good medicine) and not just looking the most “perfect” in a performance.

Good using of Nolan’s concept of “making community” Meggan. Dance groups have a vital function in First Nations communities as a vehicle through which songs, dances, language, and other cultural practices are maintained and perpetuated. Membership is based on being a member of a particular Nation or being married into a Nation. This is one area of exclusion, you would be surprised, that non-Indigenous people sometimes take issue with because they want to be a part of it. We’ve had non-Indigenous people ask to join our dance group and they get quite up set when we say no. It’s interesting how people can confuse this inclusiveness as being for all people.

First of all, I love that Debra Sparrow contextualized the performance by situating her connection to the land as a Musqueam woman and the location as part of the larger prec-colonial Musqueam community. I feel like that’s not something we hear about often enough, although people regularly acknowledge whose territory we are living and learning upon.

Second, to echo Meggan a bit, I also really enjoyed that Elders and children were incorporated into all aspects of the performance. In the West it seems that often children are shushed and moved out of communal artistic engagement, and the elderly are seen as non-members of society. What a beautiful thing to reinforce the preciousness of the old and young to society.

I agree with you Melissa. It is more powerful to have a welcome by a First Nation person of the territory to contextualize the performance and situate the witnesses within their territory than it is to have just an acknowledgement of the territory. Robert Davidson thanking of Debra and the Musqueam works to reinforce Musqueam’s land rights as well as assert that his dance group has respectful relationship to their Nation. This foundation aspect of protocol is central to my work on dancing sovereignty.

Your post has generated great conversation Maidson! Your observations on Indigenous professionalism is an important one. I was a part of a dance panel for the PuSh Festival last month where this issue was raised. Unfortunately, dance groups struggle to find funding from arts organizations (Canada Council, BC arts council, etc.) because of their inclusive nature. During the panel discussion I argued that our intergenerational structure is central to Indigenous professionalism as it ensures the future of our practices. It is vital to both individual and collective training. Hopefully funders will begin to recognize this. I’m glad you did!

I really enjoyed this post, Madison. I think you did a good job witnessing the event and articulating it in relation to the course, which I really appreciated and learned from. One part that stood out for me is the quote “one of the museum curators introduced Robert Davidson as a visual artist, detailing the collection of masks that reside in the Vancouver Art Gallery itself, that would be danced to life throughout the performance” (paragraph 3). In my beliefs and teachings, masks have a spirit of their own. I have myself wondering how do spaces like art galleries, museums or other colonial spaces impact these spirits? Are the masks still “alive” when in these spaces or do their spirits go to sleep until properly re-awakened? I think the answer is complex and depends on the teachings specific to each mask. However, it still has me thinking. Awesome job 🙂

I did not get to see this dance group perform. I have watched several utube presentations and would love to have explained a couple of the dances so I understand better what is happening or what the songs they are singing are saying.