I wanted to start out by noticing that almost all of us had a reaction to the Barthes’s text “The Death of an Author” and like most of you I have also decided to write on this but also on Foucault’s “what is an author?”. I started by reading Barthes’s “The Death of an Author” and then Foucault “what is an author?”, but after reading both I think we should start with “what is an author?” Because in order to kill the author we need to define it. When reading Foucault I felt that he was trying to find anything we can question regarding an author, he gives a lot of question but not that many answers and the answers he does give I find a little vague. He start questioning what is a “work” and only in this little word we can spend countless hours defining what “works” are but I did find this interesting. Of course I agree with Foucault that not everything writing is a work (eg grocery list) but I also have to say that I believe there is and intent of the writer for what is being written to live on and Foucault talks about this when he relates death to writing and immortalizing. He gives the example of Sadins writing in jail and weather that is a “”work”” and I think is because there is a difference in writing when you are writing so others will continue to read your text in the long run and writing just for yourself or just to inform. I think of the difference between journalistic writing and literature. Foucault then goes on to talk about the authors name and the importance of it and how an author’s name is a “proper name” which entails more than just referencing someone. And I found interesting the relation he makes to the name of an author and science how in the past even in a name had authority, one could just put a name to a text and it would be considered true, even when talking about scientific terms. Later he mentions in the 17th and 18th century this shifted and the author function in science faded away. This made me think how the name of a author today in science is not as important as the title of the person (eg phd…) and the institution associated with and how these two things gives validity to what is written now in day. Lastly another thing that stood out to” me was the idea of authors being “”transdiscursive””, and I liked this idea because it differentiated the different types of authors and how authors like Marx and Freud not only influenced their own work but also “the possibilities and the rules for the formation of other text”(pg 114) One thing I would add and maybe is implied in the text because the term used is discourse which is more than just written works but how what these “founders of discursivity” influence our everyday speech in a way they modify language. Like the example we talked about in class of every one using the term “conscious” that comes from Freud. In the end I think that Foucault question everything related to an author and in a way makes more complex the process of defining who the author is, since we need to define all these other terms ( like what is works…) in order to define the author.

I wanted to start out by noticing that almost all of us had a reaction to the Barthes’s text “The Death of an Author” and like most of you I have also decided to write on this but also on Foucault’s “what is an author?”. I started by reading Barthes’s “The Death of an Author” and then Foucault “what is an author?”, but after reading both I think we should start with “what is an author?” Because in order to kill the author we need to define it. When reading Foucault I felt that he was trying to find anything we can question regarding an author, he gives a lot of question but not that many answers and the answers he does give I find a little vague. He start questioning what is a “work” and only in this little word we can spend countless hours defining what “works” are but I did find this interesting. Of course I agree with Foucault that not everything writing is a work (eg grocery list) but I also have to say that I believe there is and intent of the writer for what is being written to live on and Foucault talks about this when he relates death to writing and immortalizing. He gives the example of Sadins writing in jail and weather that is a “”work”” and I think is because there is a difference in writing when you are writing so others will continue to read your text in the long run and writing just for yourself or just to inform. I think of the difference between journalistic writing and literature. Foucault then goes on to talk about the authors name and the importance of it and how an author’s name is a “proper name” which entails more than just referencing someone. And I found interesting the relation he makes to the name of an author and science how in the past even in a name had authority, one could just put a name to a text and it would be considered true, even when talking about scientific terms. Later he mentions in the 17th and 18th century this shifted and the author function in science faded away. This made me think how the name of a author today in science is not as important as the title of the person (eg phd…) and the institution associated with and how these two things gives validity to what is written now in day. Lastly another thing that stood out to” me was the idea of authors being “”transdiscursive””, and I liked this idea because it differentiated the different types of authors and how authors like Marx and Freud not only influenced their own work but also “the possibilities and the rules for the formation of other text”(pg 114) One thing I would add and maybe is implied in the text because the term used is discourse which is more than just written works but how what these “founders of discursivity” influence our everyday speech in a way they modify language. Like the example we talked about in class of every one using the term “conscious” that comes from Freud. In the end I think that Foucault question everything related to an author and in a way makes more complex the process of defining who the author is, since we need to define all these other terms ( like what is works…) in order to define the author.

Category: Barthes

Death of the author?

Both Barthes’ “The Death of the Author” and Foucault’s “What Is an Author” are very stimulating, insightful texts that do exactly what Dr. Freilick identified as one of the primary goals of this course – they make us question our assumptions. I strongly believe that this is a foundational exercise of our education and I have always been an avid proponent of the practice of sharply questioning what you believe and what you know.

Having said that, when it comes to soundly convincing me, both of these texts – considered either individually or in conjunction – have a limited effect. I have been exposed to them before in English Lit courses and I made a conscious effort to approach the texts open-mindedly, trying to erase my memories of the fact that they did not sway me in the past either, as it has now been a few years since Intro to Literary Analysis in my English major and consequently more exposure to literature, both of the English and Hispanic worlds. However, I find myself somewhat at odds with some of the arguments that the texts put forth. I agree that the author is a product of society, and I definitely do not believe in seeking the “explanation of a work in the man or woman who produced it” (Barthes 143) – as I believe that that is a very dangerous and pointless trap, as we were discussing in class during out last meeting. This is also certainly a very tempting path to take; I have found myself forcing an interpretation on a text because of socio-historic and biographical information that we have the privilege of knowing about the author – and I have to at times actively stop myself from doing this.

However, I do not believe that we have yet reached – and I wonder if we ever will – the point at which language can ‘act’ and ‘perform’ in a completely empty vacuum. As Barthes points out, Surrealism did indeed contribute to a desacrilization of the Author through its characteristic ‘jolt’, the practice of automatic writing, and the principle and experience of several individuals writing together, yet can Surrealism ever be fully separated from André Breton, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel (yes, I do choose to see them as ‘authors’)? In my opinion, to do so would be to also bring about a loss – while we must take every caution to not let historical and biographical information overshadow and control our view of a work, I believe that it can enrich it. A piece of literature can certainly stand independent of its socio-political context, but is it not also true that grasping this context might also be beneficial? I believe that this is particularly true in texts that share an intrinsic link to moments in history and political movements – for example, as I am conducting my thesis research on the Spanish Civil War, I cannot imagine getting a holistic picture of the literary texts (and films) that I am analyzing without having first understood the historical context of the times. When it comes to Barthes’ argument that once the Author is removed, “the claim to decipher a text becomes futile” (147), I am also not sure I agree – one can certainly parse a text and engage in an exercise of ‘interpretation’ without working in the dimension of the Author.

One portion of Barthes’ argument that I very much admire, however, is his concluding call for making the reader “the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost” (148) and his proposition that the unity of a text lies “not in its origin but in its destination” (148). I think this highly crucial to the practice of reading, but I am just not convinced that it absolutely has to come at the expense of the death of the Author; is there no space for the co-existence of both the birth of the reader and the death of the Author? Undoubtedly such an argument does not pack the rhetorical punch of setting up a ‘life/death’ dichotomy as Barthes unequivocally does in the closing sentence of “The Death of the Author,” but I believe that this is much closer to where the field stands at this time – in my personal experience at UBC.

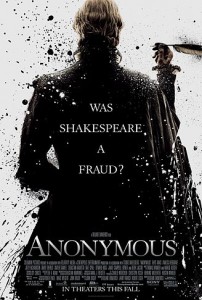

To answer Beckett’s question, I do believe that it does matter who is speaking, and while the work may possess “the right to kill, to be its author’s murderer, as in the cases of Flaubert, Proust, and Kafka” (Foucault 102), I don’t believe that it has. As we have the advantage of time and hindsight (only up to the present date, of course), we can ask ourselves if “as our society change[d], the author function will disappear” (119). Have we “no longer hear[d] the questions that have been rehashed for so long: Who really spoke? Is it really he and not someone else? With what authenticity and originality […]” (119)? I would venture to answer that on the contrary, these are questions that still very much continue to dominate our contemporary literary discourse – just one example would be the relatively recently released film Anonymous (2011) (the film essentially presents the possibility that Shakespeare did not actually write any of the works that are attributed to him). Any B.A. student at UBC who wants to obtain an English Lit major must meet the requirement of taking a 3 credit course focused on either Chaucer, Milton or Shakespeare – bringing to mind the infamous ‘cannon’ debate. However, what is most important thing to keep in mind is not the obligations of an English Lit degree, but whether or not this is a damaging thing to inflict on students, a negatively-impacting the-Author-is-very-much-alive type of view – and to that, my answer is a resounding ‘no’.

To answer Beckett’s question, I do believe that it does matter who is speaking, and while the work may possess “the right to kill, to be its author’s murderer, as in the cases of Flaubert, Proust, and Kafka” (Foucault 102), I don’t believe that it has. As we have the advantage of time and hindsight (only up to the present date, of course), we can ask ourselves if “as our society change[d], the author function will disappear” (119). Have we “no longer hear[d] the questions that have been rehashed for so long: Who really spoke? Is it really he and not someone else? With what authenticity and originality […]” (119)? I would venture to answer that on the contrary, these are questions that still very much continue to dominate our contemporary literary discourse – just one example would be the relatively recently released film Anonymous (2011) (the film essentially presents the possibility that Shakespeare did not actually write any of the works that are attributed to him). Any B.A. student at UBC who wants to obtain an English Lit major must meet the requirement of taking a 3 credit course focused on either Chaucer, Milton or Shakespeare – bringing to mind the infamous ‘cannon’ debate. However, what is most important thing to keep in mind is not the obligations of an English Lit degree, but whether or not this is a damaging thing to inflict on students, a negatively-impacting the-Author-is-very-much-alive type of view – and to that, my answer is a resounding ‘no’.

In order to achieve a cohesive understanding of our assumptions, we cannot push aside questions of “What are the modes of existence of this discourse? Where has it been used, how can it circulate, and who can appropriate it for himself? What are the places in it where there is room for possible subjects? Who can assume these various subject functions?” (120). these are the fundamental questions to the practice of questioning assumptions and sharply analyzing and also questioning the world around us – and my argument is that the birth of the reader does not have to come at the expense of the death of the author; an in-between space is indeed possible, and I believe that this is what we achieve in the literature classes that make up the Master’s and PhD programs that we are currently enrolled in.

“What is an Author” or “What is a reader”

Is his death necessary?

I remember that when I was in elementary school, the most common question in the tales that were on the textbooks of Literature was: “What does the author wants to say?” Roland Barthes would find this question terrible, castrating. And so do I. I think that the question should be: “What does the text says to you?” In Literature (and in Art in general), nobody has the last word. The interpretation that one could give to a text is as valid as the idea the author has of it. I remember a Peruvian writer who attended to a conference about one of his novels. At the end he said: “I didn’t know that I wanted to say so many things.” So, I agree with Barthes that we shouldn’t give to the author the category of “God”, the one who has the last and real opinion or interpretation of a text.

But I can’t agree with Bathes when he radicalizes his argument and says: “To give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing” (147). Really? In my opinion, the problem of this asseveration is its generalization. Sometimes, knowing the author, his biography, his possible intentions and other details that surround his work, far from “close” the interpretation, gives new clues. I will illustrate my point with an example. The following is a poem of the Peruvian poet César Vallejo (here is the English translation: http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/15272):

A MI HERMANO MIGUEL

In memoriam

Hermano, hoy estoy en el poyo de la casa.

Donde nos haces una falta sin fondo!

Me acuerdo que jugábamos esta hora, y que mamá

nos acariciaba: “Pero, hijos…”

Ahora yo me escondo,

como antes, todas estas oraciones

vespertinas, y espero que tú no des conmigo.

Por la sala, el zaguán, los corredores.

Después, te ocultas tú, y yo no doy contigo.

Me acuerdo que nos hacíamos llorar,

hermano, en aquel juego.

Miguel, tú te escondiste

una noche de agosto, al alborear;

pero, en vez de ocultarte riendo, estabas triste.

Y tu gemelo corazón de esas tardes

extintas se ha aburrido de no encontrarte. Y ya

cae sombra en el alma.

Oye, hermano, no tardes

en salir. Bueno? Puede inquietarse mamá.

(source: http://www.literatura.us/vallejo/completa.html)

Of course, one could give an interpretation of this poem without knowing anything of the author and his life. But, it is not casual, I think, that in many of the critical editions of the poems of Vallejo and in the university classes about him, is taught that he actually had an older brother named Miguel who died tragically in 1915 and that in some editions appears that “In memoriam”. This fact help us to understand better the poem, to decipher the ambiguity that the poetic voice creates with the game of hide and seek that is presented in the verses. So, knowing this, “impose a limit on that text”? I think not. On the contrary, it gives an important clue and opens the interpretation to many more variants (the notions of death that could be underlined, the not acceptance of it, the sense of absence, the love between brothers, etc.).

In my opinion, Barthes makes an important contribution highlighting that the readers have the power to appropriate the text. Taking his metaphor that the Author is like the father of the text, we could say that, as Son, the text has his own life, creates his own relations with the readers. But, saying that “the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author” (148) seems too much to me. The author could provide an important approach, no the definitive, but at least something to take into consideration. In synthesis, we should make a demystification of the author, but not “kill” him.

[César Vallejo and his last wife, Georgette, in Paris, where he was auto-exiled from 1923 until his death in 1938]

Barthes proposal elaborates about who should defines the act of literature. He defends the idea that the Author is “a modern figure” that has been supported by the positivism, the culmination of capitalism, and now (in 1967), he argues literature can not rely on the Author but the Reader. The Author, says Barthes, is “to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing” (147). The Reader, however is a “space” where all the quotations holds together and all the traces find a field.

I agree a lot with Barthes. It is true that the Author became in a mercantilist object, a name who can probably sells or not. For instance, Joanne Rowling had to change her name to J. K. Rowling so it could be most “memorable” for readers. As you probably know, many publishers analyze the names of Authors for marketing process, because is not a person whose name will appear on the cover of a book, is a “brand”, you are selling a product.

I agree also with the idea that critic uses to rely on how to identify episodes of the novels with the real life of the authors. It is pretty common. And easier. Sometimes readers need to feel that behind those amazing stories is a real person who lived those actions, therefore, they empathize with the Author because it seems that not everything that he or she wrote was really made up.

Sometimes, literature itself, disputes the idea of what is an author. In Summertime (2009) J. M. Coetzee, South African writer and Literature Nobel Prize 2003, presents the third part of what it is known as his fictionalised autobiographical trilogy (the first and second parts were Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life (1997) and Youth: Scenes of Provincial Life II (2002)). The novel was built with different points of view: some of them are interviews that a journalist carry out with the purpose of finding out how was the life of the writer J. M. Coetzee, who is already dead when the interviews take place, once he returned from USA to South Africa; some parts seems like notebook notes, a diary written by John Coetzee, where the readers can see ideas that spin around John Coetzee’s mind. In the book occurs something unusual for a autobiography: John Coetzee is created from many perspectives. Old lovers or acquaintances tend to describe John Coetzee as a cold, aloof, and odd man. Some says that he was really into languages. None of them remember him as an attractive or handsome man.

The intriguing fact here is that the “autobiography” is written by J. M. Coetzee, so he is making fiction to deconstruct the link that relates the character John Coetzee with the real writer J. M. Coetzee. Is also known that Coetzee does not offer many interviews and he do not talk much about his real life. Here, then, he offers a fictionalised idea of his life, that maybe has some brushstrokes of his reality, and maybe those readers who want to relate his fiction with reality can be a little satisfied.

Second, I know the Reader is an abstract idea on Barthes’ essay. However I can not stop thinking who could ever be that reader. Are all of us readers or only a selected group of people, who really knows that quotations and traces, can be? When Barthes said that the reader is a “space” I wonder if is a metaphor of a library, the Borges paradise. Or perhaps that idea of the Reader is Borges himself, this incredible good memory reader who, in spite of his blindness, was also a writer. I am thinking if we can be those kind of Readers. I do not have Borges’ memory, I do not belong to that elite where he grew up and belonged, I do not speak the languages that he spoke. Maybe I am a reader not a READER.

Perhaps the Reader is this ideal person who can discover a text and try to identify it. Wait: is not that a critic? But if the critics are only dedicated to the “task of discovering the author” (147), can be a critic a Reader or not? I am actually not sure about the definition of Reader. I am not sure if Barthes is talking about the reader as an human being that still is “pure” and “naive”, and only reads for pleasure, and in this condition can interpret the reading with a clarity that a critics are not longer able to use because they have been corrupted for the critic’s vision.

In this order of ideas, maybe that Reader, still naive and pure, will probably need to identify himself or herself with the Author, and will try to find the Author behind his or her work… And the cycle will never ends.

Pour les francophones, voici un lien qui vous permettra de prolonger la réflexion sur la “mort de l’auteur”: http://litterature.ens-lyon.fr/litterature/dossiers/themes-genres-formes/la-figure-de-lauteur

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes takes up the challenge posed by Ferdinand de Saussure in his Course in General Linguistics: to elaborate “semiology” as what Saussure terms “a science which studies the role of signs as part of social life” (15). Or to put this another way: Barthes takes the world around him as a social text, which can be read more or less like any other and in which the elements that compose it are almost as arbitrary as any other.

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes takes up the challenge posed by Ferdinand de Saussure in his Course in General Linguistics: to elaborate “semiology” as what Saussure terms “a science which studies the role of signs as part of social life” (15). Or to put this another way: Barthes takes the world around him as a social text, which can be read more or less like any other and in which the elements that compose it are almost as arbitrary as any other.

But the social text is only almost as arbitrary as any other; for Barthes, we also need “to pass from semiology to ideology” (128), that is, to recognize that the myths that structure the text of everyday life are politically motivated. To adapt a line from Marx: the ruling myths of each age have ever been the myths of its ruling class. There is therefore often a rather complex play between arbitrariness on one level and necessity (or, at least, political motivation) on another.

Wine is a perfect instance of this combination of extreme malleability and narrow determination. As Barthes observes, in France wine “supports a varied mythology which does not trouble about contradictions” (58). For example, “in cold weather it is associated with all the myths of being warm, and at the height of summer, with all the images of shade, with all things cool and sparkling” (60). Indeed, Barthes notes that the fundamental characteristic of wine as a signifier is less any particular content or signified to which it is attached than that it seems to effect a function of conversion or reversal, “extracting from objects their opposites–for instance, making a weak man strong or a silent one talkative” (58). And yet however much Barthes makes hay of this chain of associations and contradictions, there is a point at which the arbitrary play of significations ends. For wine is still, fundamentally, a commodity; in fact, it is big business. The analysis therefore concludes with a sort of determination in the last instance by the economy:

There are thus very engaging myths which are however not innocent. And the characteristic of our current alienation is precisely that wine cannot be an unalloyedly blissful substance, except if we wrongfully forget that it is also the product of an expropriation. (61)

Hence for this reason, if no other, Barthes is far from suggesting some kind of interpretative free play: there is clearly a right way to read the myth of wine, and a wrong way; if we leave out the fact of expropriation, we have ultimately not understood the myth or its social function.

Elsewhere the moment at which interpretation comes to an end is rather more complex, and perhaps more interesting. Take the essay on “Toys.” This is basically a critique of realism. Let us be clear: the problem with conventional French toys, Barthes argues, is not so much that they are gender-stereotyped, that for instance girls are to play with dolls and boys are given toy soldiers. It is, rather, that toys are almost always loaded with meaning: “French toys >always mean something, and this something is almost always entirely socialized” (53).

Toys constitute, in other words, what Barthes elsewhere terms a “work” in contradistinction to a “text”; they limit the range of uses to which they can be put. Indeed, they limit children’s activity and expectation of the world to one predicated on use, rather than pleasure; on interpretation, rather than creation. And for Barthes use and meaning are both forms of tyranny, and they are both essentially dead. As he says of modern toys that are “chemical in substance and colour,” they “die in fact very quickly, and once dead, they have no posthumous life for the child” (55).

What’s curious, however, is the reading that Barthes provides, by contrast, of wooden blocks. Such toys are closer to a text than a work: they have no pre-set meaning; they are not premised upon representation, and so do not depend upon interpretation; the child who plays with them “creates life, not property” (54). So far, so good. But the strange moment comes when Barthes associates the open textuality facilitated by such open-ended play with wood. In a sort of poetic reverie, he praises the many characteristics of a substance that is “an ideal material because of its firmness and softness, and the natural warmth of its touch. Wood removes, from all the forms which it supports, the wounding quality of angles which are too sharp, the chemical coldness of metal” (54).

It’s not obvious, after all, that wood is any more “natural” (or indeed, any less “chemical”) than metal. Here, the point at which the play of signification stops depends less upon a political analysis of exploitation and expropriation, and rather more on a very familiar contrast between nature and industry, tradition and modernity. In short, here at least Barthes seems to be caught in a myth that he has merely made his own.