Ben Reimer – 12/11/15

The future of cities and the role infrastructure plays in shaping how they evolve is unknown. However, when looking at the introduction of the autonomous vehicle, and speculating on whether or not it will become a key component in the transportation network of the city, this starts to inform the types of decisions that could be made in regard to infrastructure. This essay looks at the typical design of city streets in Vancouver and what they may look like in the future in a scenario where autonomous vehicles have become a primary mode of transportation for dense urban centers. In order to discuss this, it is important to first describe the assumptions that are made in relation to the adoption of the autonomous vehicle and its role in society in order to then speculate on its effect on infrastructure. The first assumption is that all cars will have some sort of autonomous capability; meaning that all drivers will have the option to either take control or give up control to the self-driving car at any time. Secondly, it is assumed that many people will no longer choose to own their own car, but instead rely on a car sharing program similar to car share programs today. Third, it is assumed that with this new technology for self-driving cars, the efficiency of travel will be much higher, especially in areas which are completely autonomous; this means that cars will be able to move at a constant rate and be able to efficiently move through the city without causing congestion on main streets. The cars will be able to learn how cities work and which streets are most efficient for traffic. With communication between cars, the vehicles will move traffic more efficiently than human control could ever have. Therefore, with a new efficient network of vehicles in dense urban cities, there will be a reduced demand for certain streets to be used by vehicles, resulting in a new street grid which allows for fewer traffic lanes, and a more pedestrian oriented streetscape.

Historically, streets have been predominantly used by pedestrians. Before the 1920s and the rise in popularity of the automobile, cars were seen as intruders which were violating the use of streets.[1]Peter Norton, in his book titled Fighting Traffic suggests that the automobile destabilized the social structure of streets, causing congestion and accidents to become quite common.[2]The number of cars that were using roads grew from 8,000 in 1900 to 8 million by the 1920s, which meant that the infrastructure for these vehicles needed to be designed to accommodate this new form of transport which was becoming so popular.[3]With the production of better roads, automakers could produce faster cars requiring even more refined roadways, which along with the new planning of suburbs to combat congestions in cities, meant that infrastructure design was playing an important role in shaping how cities evolved.[4]As cities have continued to grow and become denser, especially in the case of Vancouver, there has not been a significant change to the way streets are designed and how they function. Infrastructure design and city planning has been based on the role of the automobile since cities became dominated by the automobile in the 1930s.[5]However in the future, with the evolution of the autonomous vehicle, the emphasis can shift away from designing for the automobile, and the existing streets we have today can be reimagined.

Looking at the city of Vancouver, which is an example of a fairly dense urban center, it can be understood that traffic congestion is a common issue. The streets have stayed the same, while the amount of people using them has increased substantially. What is interesting about Vancouver is that it has a fairly small downtown core which is home to the central business district and the majority of retail, all bounded by the ocean and only about 4 kilometers from end to end. This means that the downtown core is easily accessible to pedestrians; however there is still a high priority given to vehicles for the use of road. This vision for the future of the streets of Vancouver is that the downtown core is turned back into a pedestrian focused city which shifts the priority of roads back to pedestrians similarly to how it was before the adoption of the automobile. This could be achieved by a reorganization of city streets which is aided by the reduced demand for street space from cars by the future adoption of the autonomous vehicle.

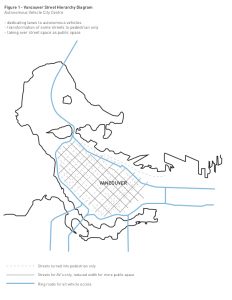

In Vancouver and other similarly dense cities, the center is often the most pedestrian dominated which means that traffic in this area can provide a significant obstacle for pedestrian flows. Looking at the map below (Figure 1), it can be seen that a new hierarchy will be given to the order of streets in Vancouver. First, the main through roads will be located at the edges, allowing for higher speed traffic and promoting drivers who are not going into the city center to take this alternate route around the city, thus reducing the amount of cars within the center. The goal for this is to reduce the amount of traffic within the core of the city, which will allow for a number of streets to be reimagined for alternative uses. As we move closer to the center of the city, the remaining streets used by cars will move at a lower speed along with a more efficient traffic flow of autonomous vehicles allowing for these streets to have some traffic lanes taken over for other uses.

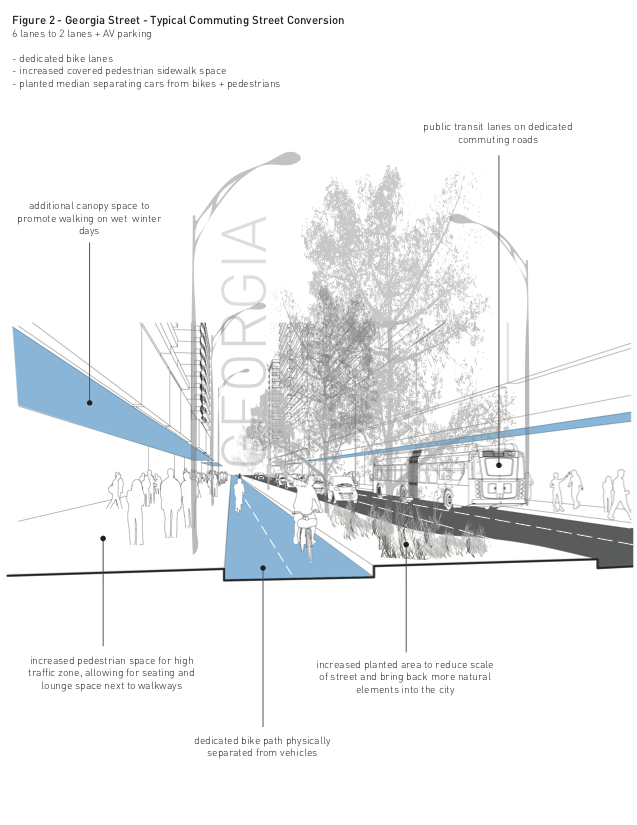

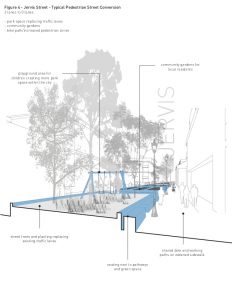

The following images (Figures 2-4) look at three conceptual ideas of how various streets in Vancouver can be redesigned. There are a number of standard street widths and number of lanes, which relate to the functions associated with each street. For this exercise, the streets chosen to focus on are the existing six lane street used as a main artery into the city, the four lane street which is associated with a typical retail environment, and a three lane residential condition.

The first condition (Figure 2) looks at the six lane Georgia Street in Vancouver which is currently one of the busiest streets in the city, functioning as a main artery and access. What this means is that it is frequently heavily congested and overused, which in the future with the evolution of autonomous vehicles will no longer be the only way to and from the city, with vehicles learning how to most efficiently navigate through the streets. Typically, these streets have a priority bus lane at the edge which is sometimes used as parking, with two main traffic lanes in both directions. Here, the street has been reduced in width to two main traffic lanes along with one main parking lane for autonomous vehicle pick-up and drop-off. This type of street has been retained as a main artery into and out of the city, however the width has been greatly reduced and the road space that is taken over is the largest, allowing for a variety of interventions. First, the north side of the street will be retained as a pedestrian thoroughfare, but widened to allow for more people as well as seating and lounge space slightly separated from the pedestrian walkways, as well as a deeper canopy over this side of the street to encourage and make walking more comfortable on wet winter days. Second, a lane here has been given priority as a bicycle only lane that is physically separated from traffic flow. This allows for cyclists to have a safer, more relaxed commute into the city. In the past, bike lanes in heavy traffic zones have typically been only given a 1.6 to 1.8 meter lane sandwiched between traffic and a parking lane, which does little to provide protection for cyclists.[6]The new 3 meter bike lane is separate from vehicle lanes with a green space which can function as a rain garden reducing the demand for storm water drainage in the city, as well as provide a visual separation between pedestrians and cars, while also allowing for a variety of planting to be reintroduced into the streetscape of the city. These larger main streets are also the location for transit pick-up and vehicle drop-off, serving as key locating streets in terms of access to and from the city. The zone for drop-off and pick-up is where users commuting into the city will be able to identify certain streets with vehicle parking which will be located a set distance allowing for minimal travel time to car pick-up. In this case, a 50% reduction of traffic lanes has been accomplished and taken over to provide alternatives to vehicle transportation; however the autonomous vehicle lanes still retain the aspects of a typical commuting street which relies on direct access to the city.

The second condition (Figure 3) looks at a four lane street, which in many cases in Vancouver is a typical retail environment which allows for a traffic lane in either direction with parking lanes at both sides. Here looking at Robson Street, there is a variety of retail and restaurant conditions that occur, which make it a very pedestrian dominated street, however with very minimal public space. For this conversion, the street has been reduced to 2 lanes, without parking but with a dedicated pick-up and drop-off zone at key points where people will be able to enter and exit their cars. This allows for the parking lanes to be taken over as public space resulting in twice the amount of pedestrian space. The aim for this conversion is to provide a more interesting retail environment for streets which are typically highly congested with pedestrians. The retail units will have the option to expand their storefront and street presence which creates more vibrant public spaces that could allow for a variety of functions to occur. In the case of restaurant or café spaces, the public patios will be able to flow onto the sidewalk providing unique spaces which encourage conversation while also benefitting the retailers by providing more customers with space to occupy. Currently in Vancouver, a pilot program has been implemented which aims to transform the street in a similar way with Parklets, which take over on street parking and provide places for people to sit, relax and enjoy the city.[7]The aim for these is to provide public spaces which attract customers to retail environments while also adding more public space which allows for more people to walk in congested areas.[8]Currently, the implementation of these Parklets seems to be challenging due to the need for retaining parking spaces in certain areas and designing them in order to work around the vehicles. With vehicles still given priority on streets, the Parklets are still fighting against cars to create public space which is not a widely accepted idea yet. However, with a reduced demand for parking with the adoption of the autonomous vehicle, this idea will become much more feasible and could become a typical part of infrastructure design for this environment. With this new public space, the streets in cities become more enjoyably places for people to use, reinforcing the idea that Vancouver is a walkable city and encouraging people to walk or bike instead of take a car as a means of transportation.

The third condition (Figure 4) looks at a smaller scale street which no longer needs to accessible to vehicles after a reduced quantity of vehicles and parking needs within the city. In this case the proposal looks at Jervis street in the west end, which has been converted from three vehicle lanes, two of which were traffic, and one parking, to zero vehicle lanes. With vehicles prioritizing the most efficient streets for traffic, and with a shift in car ownership to car sharing, the need for vehicle access and parking between every building becomes unnecessary. Certain streets will be transformed into pedestrian only streets where cars are no longer necessary, which will results in a whole new public space which can be occupied in various ways. This conversion suggests that the street is replaced with a horizontal park that can become a significant amenity in more dense residential areas where park space is limited, increasing the value of surrounding real estate and providing a stronger sense of ownership within the community. The walkways located beside the park space will retained at a width suitable for an emergency vehicle or special transportation vehicle to assist residents with disabilities in existing areas where the only access to buildings may be on a road such as this. However, for future development, the main entry to buildings can be located on streets which still allow for cars, resulting in a truly pedestrian only street. Here, there is a green space located within the center of what used to be roadway, where there can be a variety of uses. These could range from children’s play area to community gardens, both allowing for residents of the local neighbourhood to take ownership in the public space. A good example of this already being a successful way to utilize open space are the community gardens along the Arbutus Corridor which was previously a dedicated rail corridor that was abandoned from use. This space was adopted by the local residents as a place for community gardens in an area where lot sizes are quite restrictive and many people do not have enough space on their own property to have a planting bed. With autonomous vehicles shifting the focus of streets and changing the reliance on automobiles, streets such as these can become parts of the city that are no longer considered infrastructure. With roads occupying such a larger percentage of land area within cities, the overtaking of these spaces as pedestrian only allows for a new way of thinking about the city and what it can offer to residents.

The third condition (Figure 4) looks at a smaller scale street which no longer needs to accessible to vehicles after a reduced quantity of vehicles and parking needs within the city. In this case the proposal looks at Jervis street in the west end, which has been converted from three vehicle lanes, two of which were traffic, and one parking, to zero vehicle lanes. With vehicles prioritizing the most efficient streets for traffic, and with a shift in car ownership to car sharing, the need for vehicle access and parking between every building becomes unnecessary. Certain streets will be transformed into pedestrian only streets where cars are no longer necessary, which will results in a whole new public space which can be occupied in various ways. This conversion suggests that the street is replaced with a horizontal park that can become a significant amenity in more dense residential areas where park space is limited, increasing the value of surrounding real estate and providing a stronger sense of ownership within the community. The walkways located beside the park space will retained at a width suitable for an emergency vehicle or special transportation vehicle to assist residents with disabilities in existing areas where the only access to buildings may be on a road such as this. However, for future development, the main entry to buildings can be located on streets which still allow for cars, resulting in a truly pedestrian only street. Here, there is a green space located within the center of what used to be roadway, where there can be a variety of uses. These could range from children’s play area to community gardens, both allowing for residents of the local neighbourhood to take ownership in the public space. A good example of this already being a successful way to utilize open space are the community gardens along the Arbutus Corridor which was previously a dedicated rail corridor that was abandoned from use. This space was adopted by the local residents as a place for community gardens in an area where lot sizes are quite restrictive and many people do not have enough space on their own property to have a planting bed. With autonomous vehicles shifting the focus of streets and changing the reliance on automobiles, streets such as these can become parts of the city that are no longer considered infrastructure. With roads occupying such a larger percentage of land area within cities, the overtaking of these spaces as pedestrian only allows for a new way of thinking about the city and what it can offer to residents.

After looking at these three examples of how city streets may change, it is helpful to think about what the key concepts are and what the goals are for how these can be adapted. Clearly these situations are only looking at a few key conditions in the city of Vancouver, but the general idea could be implemented in other cities with similar urban conditions. For these concepts to be functional and implemented in the future there needs to be a general understanding and adoption of ideas along with a set of rules or bylaws which govern how vehicles move through it. As was said earlier, the outer streets will be places for faster vehicles passing through city, with inner streets dedicated to autonomous vehicles with set speeds, able to play a secondary role in terms of vehicle access where the focus is centered on a more pedestrian pace of movement.

In terms of the main idea and take away from this exercise, I think autonomous vehicles can play a key part in shaping the development of the city. In the past, the planning of cities has been concerned with providing adequate infrastructure for vehicles and then filling in gaps with development, but with this new model and concept for streets, the pedestrian space is given new priority. As the reliance on vehicles changes and individual car ownership becomes less common, the available land area that can be taken over for pedestrian use provides for a variety of design opportunities. The central idea for these concepts is the pedestrianization of the city center which will ultimately create a more efficient, more enjoyable way for people to interact with urban form. The streets of the future no longer need to be generic exercises in infrastructure planning, but they can become design exercises for architects, landscape architects and planners to create a more diverse, vibrant streetscape.

[1]Peter D Norton. ( 2011). ‘Introduction: What Are Streets For?’ in Fighting Traffic, 7.

[2]Norton, 3.

[3]Michael Southworth & Eran Ben-Joseph (1997). Chapter Three: Gritty Cities and Picturesque Villages in Streets and the Shaping of Towns and Cities. McGraw Hill. 56.

[4]Southworth, 60.

[5]Norton, 5.

[6]Mike Anderson. Vancouver’s Bicycle Lanes: Retrofitting Arterial Streets to Accommodate Cyclists. City of Vancouver. 2009.

[7]City of Vancouver. 2013 Parklet Pilot Program Guide. City of Vancouver, 2013. Web. Accessed Nov. 03, 2015.

[8]City of Vancouver.

References

Anderson, Mike. Vancouver’s Bicycle Lanes: RDiagram Map of Idea Georgia Street Jervis StreetJervis Street Georgia Street Diagram Map of Ideaetrofitting Arterial Streets to Accommodate Cyclists. City of Vancouver. 2009.

B.C. Road Builders and Heavy Construction Association, et al. Mmcd: Master Municipal Construction Documents. Rev. April 2000 ed. British Columbia: Master Municipal Construction Documents Association, 2000. Web.

City of Vancouver. 2013 Parklet Pilot Program Guide. City of Vancouver, 2013. Web. Accessed Nov. 03, 2015.

Cuff, D., & Sherman, R. (2011). ‘Architecture as Public Work’ in Fast-forward urbanism: rethinking architecture’s engagement with the city. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 18-25.

Halprin, L. (1972). Cities: Revised Edition. Mit Press. pp.193-207.

Norton, Peter D. ( 2011). ‘Introduction: What Are Streets For?’ in Fighting Traffic, pp 1-17.

Michael Southworth & Eran Ben-Joseph (1997). Chapter Three: Gritty Cities and Picturesque Villages in Streets and the Shaping of Towns and Cities. McGraw Hill. pp 53-76.