Lastly, I have overlaid park data for Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to highlight areas at risk.

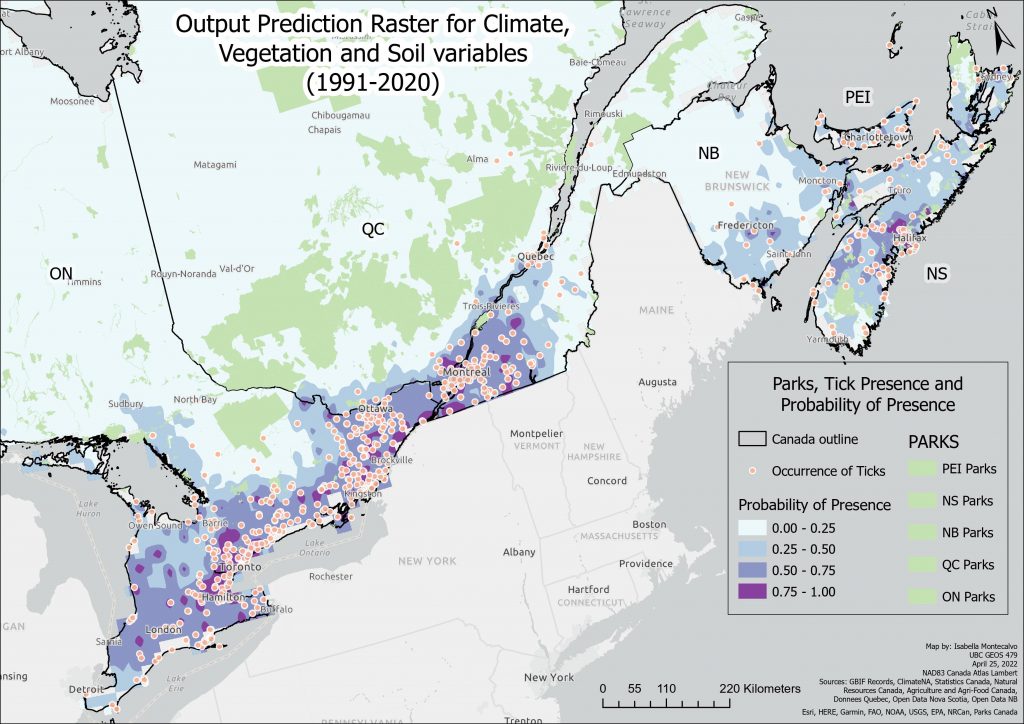

Here is the parks overlaid onto the output prediction raster for Model 1:

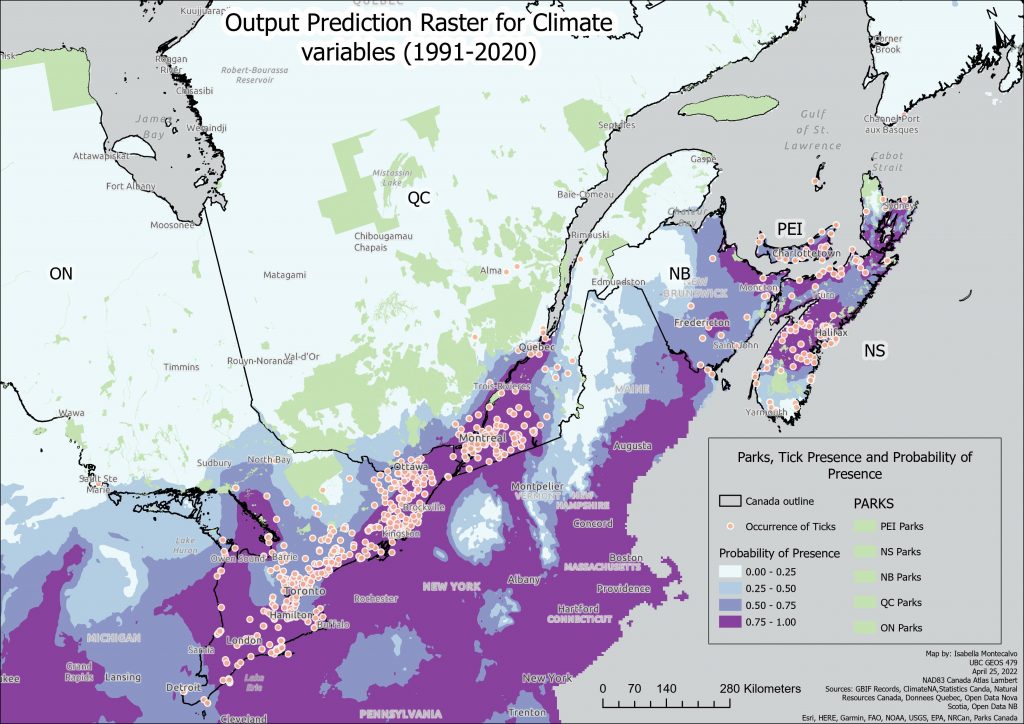

As can be seen here, there is less expansion of probability of tick presence than the other two Models, below.

A higher resolution PDF version can be found here: Current Climate Variables and Parks Raster.

Currently, parks at risk in each province include:

Directly north of Toronto, parks like Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands Provincial Park, Kawartha Highlands Signature Site park and Bon Echo Provincial Park are all areas at risk in Ontario. Places like French River Provincial park and Killarney Park to the West, Chiniguchi Waterway Provincial Park to the North in Ontario, Algonquin provincial park in Ontario (large park by North bay) are all at risk based on this model.

In Quebec, Réserve faunique de Papineau-Labelle, Aire faunique communautaire du Lac Saint-Pierre, Parc de la Gatineau, Parc national du Mont-Tremblant, Parc national du Canada de la Mauricie as well as a bunch of controlled harvesting zones along the outer reaches of the higher probability areas are all at risk.

In Nova Scotia, Kejimkujik National Park is most notably at risk. As are smaller areas such as Tangier Grand Lake Wilderness Area, Ship Harbour Long Lake Wilderness Area, Waverley – Salmon River Long Lake Wilderness Area, Cloud Lake Wilderness Area, Tidney River Wilderness Area, Kelley River Wilderness Area, Boggy Lake Wilderness, Area Liscomb River Wilderness Area, to name a few. In fact, all the parks in Nova Scotia are at risk except for Cape Breton Highlands National Park in the north.

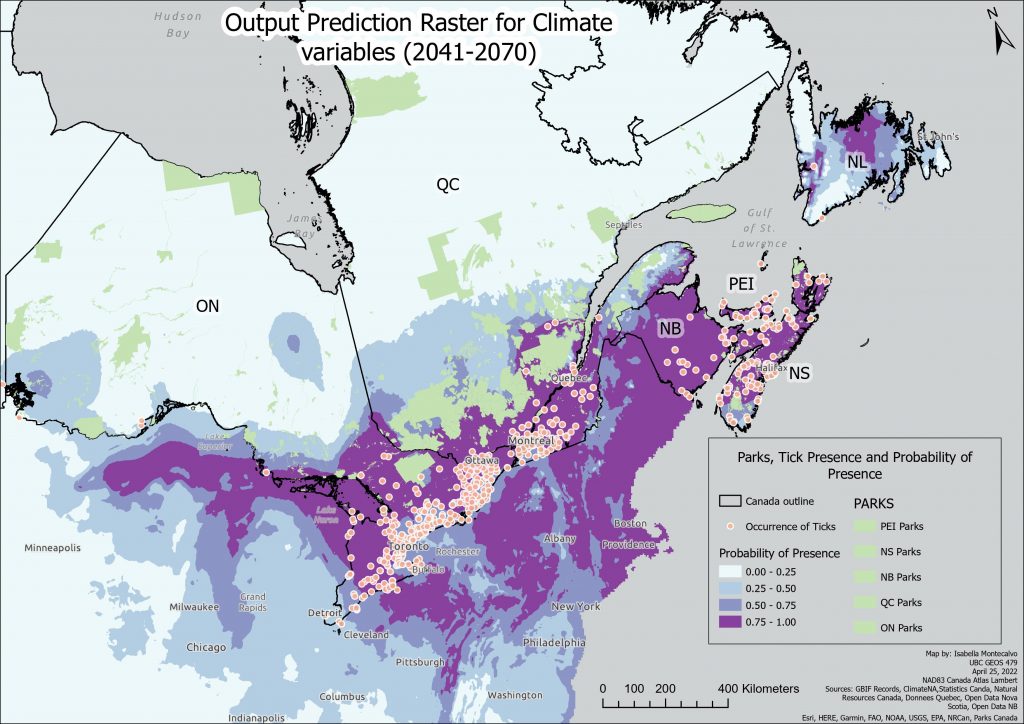

With the predictions from the future climate data, even more parks come under risk in each province.

A higher resolution PDF version can be found here: Future Climate Variables and Parks Raster.

As can be seen in this projection (smaller scale), all parks previously mentioned see a bigger probability of acquiring ticks and therefore potentially Lyme disease cases, with higher probabilities engulfing most of Quebec’s northern parks/wilderness areas, including parks like Réserve faunique de Matane and Réserve faunique des Chic-Chocs above New Brunswick. The North of Nova Scotia where Cape Breton Highlands National Park is, also becomes an area of high risk in this future prediction. Far to the West of Ontario, where previously there had been no noted probabilities of tick presence, now see 25%-50% probability, putting parks like Quetico Provincial Park and the people who visit it at risk of contracting Lyme disease. The future looks a little bleak here.

Governments recommend avoiding tall grass, carefully checking yourself, your pets and your belongings after being outdoors and at home removing dead leaves, undergrowth, wood, and weeds from your lawn, around wood supplies and the shed. If you are able to remove the tick less than 24 hours after being bitten, your risk of developing Lyme disease is low, even if you were bit in a high-risk sector. However, the risk increases if the tick remains attached for longer. It is, as a result, vital to remove the tick from your skin as quickly as possible. It is also important to note that you can contract Lyme disease again even if you’ve already had it (Gouvernement du Québec, 2021).

I hope that governments are taking note of potential Lyme disease spread and that this study may contribute to this alarm bell.