I am going to attempt to navigate and answer question number 3 that Professor Paterson put forth in this post. This inquiry calls into question the validity of Lutz’ assumption regarding the heritage of his readers – that they either belong to the “European tradition, or he is assuming that it is more difficult for a European to understand Indigenous performances”. Both pieces written by Lutz, First Contact as a Spiritual Performance: Aboriginal — Non-Aboriginal Encounters on the North American West Coast, and Contact Over and Over Again relate the first encounters, first meetings, whether purposeful or by chance, between “native and stranger” (30).

Contact Over and Over Again immediately establishes the narrative of “us and them”, a theme that we have discussed in the context of J. Edward Chamberlain’s If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? When analyzing Lutz’ writing of the first encounter of Indigenous people and the Spanish and British in the Eighteenth Century, the tale is set up in such a way to be told from the perspective of the all mighty, superior “us”, or those belonging to the European tradition. Please take this with a grain of salt, as I do mean it quite sarcastically. The excerpt below speaks directly to the “us and them” dichotomy, coming from the perspective of the Spanish pilot, Martinez:

“I asked them a thousand questions [by signs], all having to do with whether we could cast anchor, but they did not understand me, and their replies were to say that they had plenty to eat and drink if we would come ashore.” (30-31).

This excerpt establishes wonderful groundwork for what this blog is examining: is Lutz’ assumption that “One of the most obvious difficulties is comprehending the performances of the Indigenous participants” (32). Is this a fair assumption? My simple answer is no, but please allow me to explain.

This assumption, as put forth by Lutz, entails a few difficulties that I struggle to agree with. First, as stated above, the assumption itself comes from the stance that those from the European tradition were immediately superior to those of the Indigenous tradition – they cannot understand us, but we, of course, can understand them. Wherein this situation is the story from the Indigenous people’s perspective? Perhaps their performances were exemplifying particularly what they intended, and were perceived incorrectly by the strangers. Professor Paterson is being fair when pointing to this assumption, as it appears clearly in Lutz’ work, but it is Lutz’ assumption itself that stumps me.

It challenges me that Lutz discusses the “necessity [to] enter into a world that is distant in time and alien in culture” in order to perceive Indigenous performances. Why? Because from both perspectives, that of the Indigenous peoples and the Europeans, the traditions and culture that they come into contact with are alien cultures. “Both peoples sought to minimize and danger and maximize opportunities. Without a common language, both did so by performing for the other” (30). Lacking means of verbal communication that could be mutually understood, both parties relied on the use of physical performances, yet for no reason should the Europeans performances be categorized as being easier to interpret. The Indigenous peoples would be entering just as much of a strange, unknown culture with the intention to communicate as the Europeans, no? Here is a funny video about the mishaps of communication that is misunderstood, and the performance that ensues.

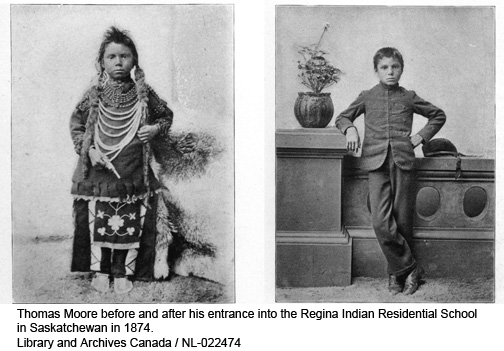

The idea of superiority of one race over the other brings me to another point of focus, of which Professor Paterson discussed in her weekly blog post: Residential Schools. In the 19th Century the Canadian government “believed it was responsible for educating and caring for aboriginal people in Canada” (CBC). The thought was to force adoption of the english language, as well as Christian and Canadian customs in order to provide the best chance of success. These values would then ideally be passed onto that generations children, and begin the “success” (HUGE quotation marks) of completely abolishing a few generations. “In all, about 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools” (CBC). This air of superiority, or the need to “better” the lives of others who hold different cultures, traditions, language, and customs, plays again into the “us and them” dichotomy, in that we have to better the lives of them because they are the ones that are different.

In conclusion, I feel Professor Paterson is spot on to dissect Lutz’ assumption from his work in Contact Over and Over Again. But, I struggle to maintain the same assumption as Lutz. In this, the works perspective appears very one sided, but perhaps that’s the only way to tell such a story of first contact. All first contact stories would vary extremely from one parties perspective versus the other’s, and I would be intrigued to hear of the same meeting from a different side.

Works Cited

CBC News. “A history of residential schools in Canada.” CBC News. 2008. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/a-history-of-residential-schools-in-canada-1.702280>.

Lutz, John. “Contact Over and Over Again.” Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indignenous- European Contact. Ed. Lutz. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2007. 1-15. Print.