Question 1 that Dr. Paterson presents in Lesson 2.3 challenges the students of English 470 to “See if you can discover how this oral syntax works to shape meaning for the story by shaping your reading and listening of the story.” This is in relation to the story “Coyote Makes a Deal with King of England”, in Harry Robinson’s Living by Stories. How does the oral translation of a story change, morph, add to, or take away, from a story? My ENGL 470 partner in crime, Samantha, was once again my go-to person to bounce this story off of, and the results that I took away from that experience were very interesting indeed.

After researching the importance of oral traditions in First Nation history and culture, a most interesting paradox became very obvious to me, and voiced by historians alike: Westerners, until recently and perhaps still, tend to think that a society without written history is a society without any history at all. This thought process could not, in fact, be further from the truth. I urge you to take a look at UBC’s very own Indigenous Foundations website, where in it are pages of wonderful readings and history.

A quote from Stephen J. Augustine, Hereditary Chief and Keptin of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council:

“The Elders would serve as mnemonic pegs to each other. They will be speaking individually uninterrupted in a circle one after another. When each Elder spoke they were conscious that other Elders would serve as ‘peer reviewer’ [and so] they did not delve into subject matter that would be questionable. They did joke with each other and they told stories, some true and some a bit exaggerated but in the end the result was a collective memory. This is the part which is exciting because when each Elder arrived they brought with them a piece of the knowledge puzzle. They had to reach back to the teachings of their parents, grandparents and even great-grandparents. These teachings were shared in the circle and these constituted a reconnaissance of collective memory and knowledge. In the end the Elders left with a knowledge that was built by the collectivity.”

A line from the middle of this quote jumps out at me the most. That is, “They did joke with each other and they told stories, some true and some a bit exaggerated but in the end the result was a collective memory.” Emile Durkheim noted that “societies require continuity and connection with the past to preserve social unity and cohesion.” (Britton). Although not using the term collective memory, all aspects of his notes reflect the importance of oral history, and the resulting collective memory produced from it.

In a fellow student’s blog discussing oral transmission of stories, the game of telephone was brought up in relation to how stories often morph dramatically through repetitive telling and re-telling. I was in strong agreement when reading this, as for anyone that has played the game of telephone knows that the word “car” can somehow become “monster” by the time it makes it from mouth to ear around the circle. Interestingly, the oral-based knowledge that is predominant among First Nations “must be told carefully and accurately, often by a designated person who is recognized as holding this knowledge.” Eric Hanson explains that the passing one of stories that may be told only during certain seasons, or in specific places, from generation to generation “keeps the social order intact” (UBC Indigenous Foundations). Because such stories are often integral in teaching lessons about culture, land, or environment, the person telling the stories “is responsible for keeping the knowledge and eventually passing it on in order to preserve the historical record.” Therefore, the oral telling of a story does not so much allow for large exaggerations or dramatic changes to the facts, but instead allows for a platform of education, passed down knowledge, and awareness of one’s culture and history.

Now, to Robinson’s story “Coyote Makes a Deal with King of England”. Through my first reading through, silently to myself, I was honestly very, very confused. Admittedly extremely uneducated about First Nations stories and culture I found it difficult to follow the sentences on the pages, to distinguish the “he” versus “they” in relation to the characters: “And he eat right there, And then they got a fire…” Robinson (64)

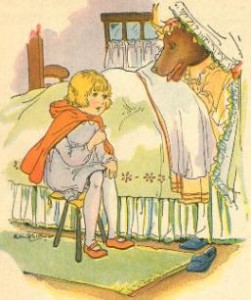

Whenever I write a paper or piece of literature for a class, I ensure that I read it allowed to myself before submitting it. I have found that this helps to alleviate any grammatical errors, or sentence structures that might make sense in my head, but certainly do not make sense to read. Paralleling this experience, when I read Robinson’s story allowed, the mysteries began to become slightly clearer than during my previous reading. I found that even adding changes to the pitch of my voice, or being able to noticeably pause at appropriate times to reflect allowed me to dive into the text. Yet, I realized I had some sort of mental block to the idea that Coyote could be perceived as a man: “Looks like a coyote but it looks like a man” (69). Perhaps a childish comparison, but this reminds me of “Little Red Riding Hood”, where the wolf dresses up as the grandmother to trick Little Red Riding Hood. (Looking back at the story this makes no sense, but neither do most childhood stories and tales). The point of this comparison is the mental block that one character could, in fact, be perceived as different versions of themselves, without the intent of evil or the elaborate description of the clothing put on to create the character. Instead, Coyote was simply seen as man.

“Oh! Grandmother, what big ears you have!”

The last stage of this experiment was to read the story to Samantha, and have her read it to me. For those of you who haven’t met this wonderful young woman, she has the ability to add… “pizzaz” if you will, to any situation. Therefore, reading it to her I found I was slightly timid because I was still failing to thoroughly grasp the entire story. Yet, Samantha read the story and although she way not have understood it thoroughly either, it was the oral syntax that she applied to it – the language used, the tones of voice, the pauses, and elaboration of certain parts that made the story what it was to listen to.

I hold true to the idea that having the ability to tell a story, both entertaining and engaging, is a gift. Even if one does not fully understand the significance or meaning of the story, sharing in the oral creating or telling of a story is a rewarding experience. For those that have not read “Coyote Makes a Deal with King of England”, I encourage you to follow the guidelines presented in Question 1 and see how each step changes your interpretation and understanding of it.

Thank you for reading!

Gillian

Works Cited

Britton, Dee. “What is Collective Memory?” Web. <http://memorialworlds.com/what-is-collective-memory/>.

Hanson, Eric. “Oral Traditions.” Indigenous Foundations. Web. <http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/culture/oral-traditions.html>. 2009.

Robinson, Harry. “Coyote Makes a Deal with the King Of England.” Living by Stories: a Journey of Landscape and Memory. Ed. Wendy Wickwire. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. 64-85.

Hello Gillian!

Thanks for your spirited reflections on the role of orality in First Nations narratives as well as in your own writing. Using an oral rendition of your writing as a way of proofreading also emphasizes the role of oral practices in contributing to clear writing, reinforcing the complementary, rather than dichotomous, balance between orality and literacy. Also thank you for including the quote from Chief Augustine; his words provided a clear firsthand account of the oral peer-review practices that he has experienced. I know Chris Cheung has discussed this topic on his 2:3 blog, too. It might be worth checking out if you’re interested in another perspective on this topic.

I was very amused by your connections between Coyote and the Big Bad Wolf. It seems to me like the grandmother disguise would be totally up Coyote’s alley, but then I feel Coyote would be more interested in pilfering the contents of Little Red Riding Hood’s basket than anything more nefarious. Do you see Coyote in any other childhood stories, and if so, do you think Coyote would stick to the script as we expect it?

Hey Gillian!

I read through “Coyote Makes a Deal with the King of England”, just silently, to myself, and I have to admit, I was incredibly confused. I understood the basics of the story, and did my best to follow along, but, as you say, the switch in pronouns (he to they) was incredibly confusing. I also found that the number of sentences that begin with the word “and” threw me off. The sentences were short and often abrupt, creating pauses where I didn’t expect there to be pauses. “And he eat right there.

And then they got a fire.

And the fire, they never go out.”

So I was wondering what your thoughts on those aspects of the story-telling are, and whether you think that’s deliberate, or just the way the story was told and transcribed.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, and the quote from Chief Augustine!!

Thank you for your comments!

Keely – I think Coyote can be applied to a number of characters, whether in children’s stories or others. I think the basis of his character reflects a commonality amongst stories – the outlier character of sorts. Sneaky in his own way, slipping between the cracks and always causing amusement and entertainment. From what I have learned about him, I certainly don’t think Coyote would stick to the script! He is a somewhat off the cuff character it seems and always a surprise.

Cat – for the sentences starting with “and” I believe that there in lies an aspect of transcribing stories that are usually told orally. When listening to a story, you don’t see the sentences as they are laid out on a page; you just listen and let the story feed its way into your mind as it is. Yes, as soon as it is visually represented in front of you, the automatic response is to look for structure, and try to follow the layout on the page for direction and guidance as to how to read the story.

I don’t think it’s deliberate in the sense of making the story deliberately difficult to read – I think that’s simply how it was transcribed and told, and the transfer process makes it somewhat difficult to follow.

Thank you!

Gillian