For lesson 3.3, I was assigned to examine pages 162 – 177 of Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water. I was thrilled to be assigned this section, as it focuses primarily on the interactions and relationships of Karen and Eli, and Lionel and Alberta, respectively. The structure is interesting in that the time period of the narration continuously shifts from present to past. In pages 162 – 166, the narrative voice discusses the relationship of Eli and Karen, and takes him from reading a book on the couch, to reminiscing of meeting Karen’s parents. Pages 167 – 1173 have the same structure, but focus first on Lionel’s interactions with the Native American elders Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye. Finally, 174 – 177 offer a view of the struggle of Lionel’s partner, Alberta, in wanting children but not marriage or a relationship.

Classic visual interpretations of Hawkeye, Robinson Crusoe,

Lone Ranger, and Ishmael

Green Grass Running Water is so thick with historical points and intricate character development that I simply cannot cover everything in this blog. Therefore, I am going to focus primarily on a few main points: Alberta Frank, Eli, and how the quintessential Canada is pulled into question by King.

Alberta Frank

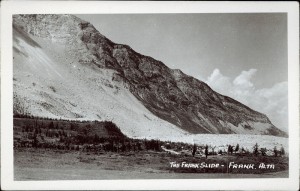

I found the character of Alberta most interesting, and therefore will begin with her. Obviously, her name matches that of the Canadian province of Alberta. She is the main female character in Green Grass Running Water, and as Jane Flick explains, “King may be showing a little fondness for the province itself since he lived in and taught in Lethbridge, Alberta, from 1980-1990” (144). Alberta’s last name, Frank, can also be speculated to refer to the town of Frank, Alberta, on the Turtle River. “This town was a major disaster site, buried by the famous Frank Slide of 1903″ (Flick, 144). This was Canada’s deadliest rock slide, killing 90 people in less than two minutes, when 82 million tons of rock fell from the summit of Turtle Mountain into the Crowsnest River valley below (Frank Slide Interpretive Centre). Rapidly changing weather is thought to have played a large role in the cause of the slide – heavy snowpack followed by unseasonably warm temperatures, and then a rapid, deep freeze. This deep freeze caused expansion of the previously melting water, creating a powerful wedge that drove the section of rock away from the mountain face. The sound of the sliding rock was so significant that it was heard up to 200 kilometres away from the site itself.

The Frank Slide, 1903

A main conflict in this section of the novel, both a moral and societal dilemma, surround the issue of Alberta wishing to have a child outside of the confines of marriage, or a relationship at all. King highlights her independence:

“I’d like a room for the night.”

“Mr. and Mrs.?”

“No, a room for one.” (174)

And furthermore (bolding added for emphasis):

“Does the lady have a major credit card?”

Alberta put her card on the desk.

“Does the lady have a car?”

“The blue Nissan parked next to the red thing.”

“And does the lady require any help with her bags?”

Alberta smiled and leaned forward on the counter. (175)

Alberta evokes her independence through limited dialogue, spending most of this section alone. She also seeks out routes for artificial insemination, a path in which she could bear a child without the physical or emotional aid of a partner. After conducting some research, it seems Alberta is a character ahead of her time! More and more women are choosing to have a child, or children, alone instead of sticking within the traditional realm of marriage.

The Bennett Clinic is names as one of the only clinics that “take single women” for the purpose of artificial insemination (King, 177). As Jane Flick explains, the clinic is “ironically named for R.B. Bennett (1870- 1947), a prominent Alberta politician, member for Calgary, who was Prime Minister from 1930-35″ (156).

“Most of the clinics won’t take single women. I think it’s a question of morals.”

“Morals?”

“One clinic will take single women. But you have to get a letter from me testifying to your physical health, your mental health, and your morals.”

“Morals?”

“In the first instance, they figure that if you’re not married you’re not trying. In the second instance, they figure that if you’re not married but trying hard, you’re not the kind of person they want to associate with.”

“I just want a child. I don’t want a husband.”

“The Bennett Clinic in Edmonton.” (177).

It seems odd, or perhaps indeed ironic, that an institute going against social morals would be named after the leader of Canada, and a fairly highly respected leader in that. R.B. Bennett was Prime Minister during the worst years of The Great Depression, and his leadership was not as well reflected or received as perhaps it would have been otherwise at a different time period. Perhaps these feelings are reflected in King’s use of his name.

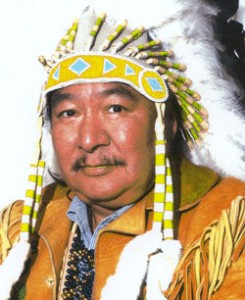

Eli Stands Alone

Eli’s name “suggests Elijah Harper, who blocked the Meech Lake Constitutional Accord in 1990 by being the standout vote in the Manitoba legislature. He voted against a debate that did not allow full consultation with the First Nations and that recognized only the English and the French as founding nations” (Flick, 150). Harper is described as the solitary voice of dissent against the Meech Lake Constitutional Accord, refusing the support the motion. Obviously, King’s creativity in giving Eli his name is quite fitting, and shows respect to the Aboriginal Leader hero that Harper is remembered as.

Throughout pages 162 – 166, there are a number of dialogue exchanges in which the social divide between Eli, an Aboriginal, and Karen and her family, is highlighted.

1. “Karen liked the idea that Eli was Indian, and she forgave him, she said, his pedestrian taste in reading, and at the end of the summer, after Karen had come back from an extended vacation in France with her family, she and Eli moved in together.” (163)

2. “Looks good,” he shouted.

“Thought you Indians had keen eyes.” Herb laughed, and he hung the bucket on the ladder and came down. (165)

As well as the differences in socioeconomic standing that are alluded to:

3. “It had always been obvious that Karen had money, and moving from his fourth-floor studio walk-up into Karen’s brownstone just off Avenue Road reminded him of the distance the two of them had crossed. The flat was simple enough and there was no conspicuous show of wealth, but even Eli could tell that the rugs on the floor were Persians and the paintings and rings on the walls were not the cheap reproductions that the university book store sold.” (163)

Would the real Elijah Harper please stand up?

(This, of course, referring to Mr. Harper standing in parliament holding an eagle feather to show his disagreement with the Meech Lake Constitutional Accord)

My final thought to try and process is the ideas of the “quintessential” Canadian that King points to in the dialogue surrounding Eli.

“That one is by A.Y. Jackson. The other is by Tom Thompson. What do you think?”

“They’re great.”

“It’s the light. It makes the land look . . . mystical.”

“They’re great.” (164)

For those of you who know art, or do not know art, I feel safe in assuming that most of us would be able to pick out a Tom Thompson painting for the recognizable Canadian landscape that he so successfully created with paint and paper. Tom Thompson was an extremely influential painter in the 20th century, and helped to establish the ground work for the later formation of the Group of Seven, unfortunately suffering a mysterious death before it’s formal establishment.

The Jack Pine

Karen’s need to point out both Tom Thompson and A.Y. Jackson to Eli remind me of how an adult might speak to a child at times. She appears to successfully insult him in a way by having to go out of her way to explain who these “true Canadian” artists are, almost as if because he is Aboriginal, he could certainly not understand or know. Throughout Green Grass Running Water there are additional allusions to Karen’s attempts to immerse Eli into Canadian culture. But this Canadian culture is her Canadian culture, making rise to the “us” vs. “them” mentality that has been discusses at length in previous blog posts.

I quite enjoyed this assignment, as it forced me to not just read the words, but examine them. Examine them for the culture context, King’s jokes, sarcasm, and history.

Thank you for reading!

Gillian

Works Cited

Flick, Jane. Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water. www.canlit.ca. Canadian Literature, 9 Aug. 2012. Web. 8 Apr. 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.