Introduction

Governance represents the ways in which rules, norms, and actions are produced, reproduced and regulated throughout a system (Darby, 2010). Consequently, ‘governance’ should not be confined to a mere understanding of decision-making processes, but extended into the realm of normative and customary practice as well. The global scale sets the precedent/the ideal for how we should conceptualize water as a resource, which in turn informs how we might conserve it for the future. Although naturally, water-related issues are spread across time and space, which poses particular challenges for different regions and communities around the world (UN-Water, 2014). If we are to analyze water supply and management trends in Sonoma County, California, we must assess the normative standards that are constitutive of regional and state-regulatory bodies, the key decision makers over water resources related to this case study.

Water management in California represents a complex bureaucratic web of laws, policies, and institutions. What follows is a brief overview of the main regulatory agencies and relevant legislation/policies that oversee water-management and supply. It is important to note that this summary deliberately focuses on the state and regional policy regime because these levels of governance dominate the governance framework (based on research).

A Governance Framework Dominated by Policy

At the global scale, the United Nations (UN) addresses water-related issues. UN-Water, an inter-agency within the UN, defines itself as a “coordinating mechanism” for issues related to freshwater, including; water quality, quantity, development, assessment, management and monitoring, use, sanitation, and water-related disasters (UN-Water, 2014). While management practices are not officially mandated by the UN, UN-Water, with the help of activities carried forth by member and partner organizations, seeks to help states reach Millennium Development Goals by pushing for an integration of water-related issues into regional development plans, for example (UN-Water Work Programme, 2015). Growing concerns over water scarcity, access to sanitation, integrated water resources management etc., as outlined in the 2015 UN-Water Governance Report, highlight the international stake in securing water resources.

At the federal level, U.S. water concerns are overseen by federal agencies like the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), and the US Army Corps of Engineers. The primary federal law governing water pollution is the Clean Water Act (CWA). The act establishes the basic structure for regulating “quality standards for surface waters,” while the EPA enforces requirements under the act by working with federal and state regulatory partners to monitor compliance (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2015). The governance framework for water management is divided between federal and state levels to an extent, but State-controlled agencies appear to lie at the apex of the system. Where some widespread legislation related to water is written/codified at the national level (e.g. Clean Water Act), regulatory compliance is typically carried out by individual states.

The California state government is organized into large cabinet-level agencies. Those pertaining to water management, use, regulation, and supply, include: The California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA) and the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA). CalEPA’s stated aim is to “restore, protect and enhance the environment to ensure public health, environmental quality and economic vitality,” whereas CNRA’s mission is to “restore, protect and manage the state’s natural, historical and cultural resources for current and future generations…” (California Environmental Protection Agency, 2015; California Natural Resources Agency, 2015). Various boards and departments also exist within both parent agencies, to account for the oversight of different resources and/or a niche area. Out of eight CNRA departments, The Department of Fish and Wildlife, The Department of Water Resources, and The Department of Conservation, have the greatest stake in protecting state waters and the wildlife that depends on it. The most relevant department within CalEPA is the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), which alongside regional sub-boards has joint authority over the allocation of water, the protection of water quality, and the administration of water rights (California Environmental Protection Agency, 2015). The SWRCB is of significant interest to the case study because “the amount of water actually used by water rights holders is poorly tracked and highly uncertain” according to Grantham (2014, p. 3). Grantham’s study further argues that the largest roadblock to water management involves the lack of accurate measure of water use. While the legislative skeleton and regulatory body (SWRCB) is clearly present, regulation has been made more difficult because water supplies are not being tracked, recorded and monitored efficiently.

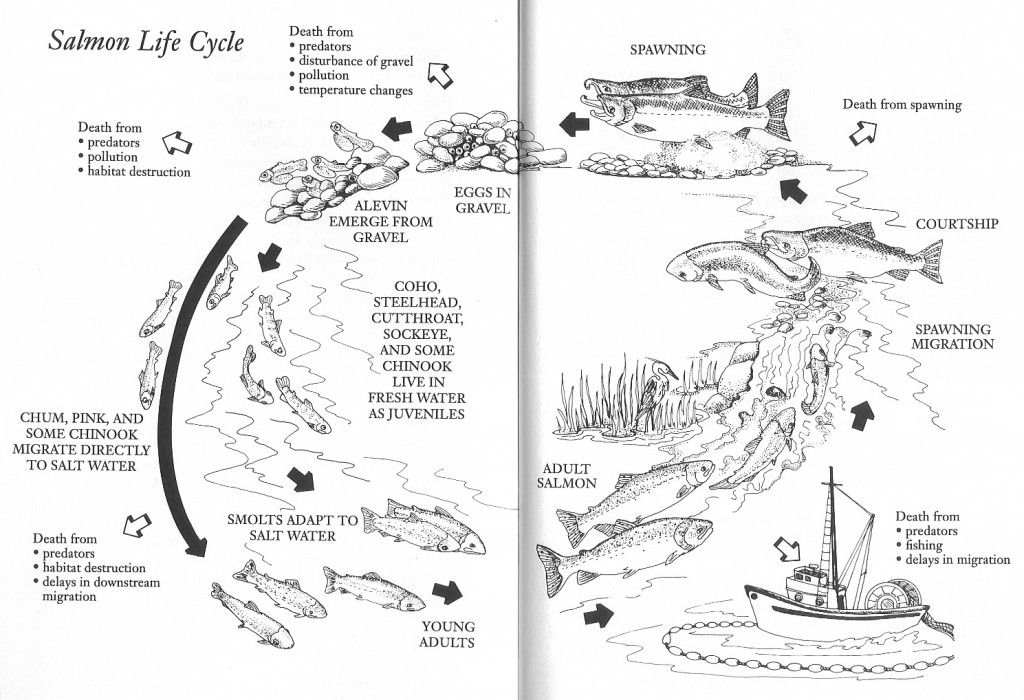

A variety of different acts, policies, and regulations are also outlined by the aforementioned agencies. For instance, the Department of Fish and Wildlife as the name states, manages and protects wildlife through its enforcement of state laws related to hunting, fishing, pollution, wildlife destruction, and endangered species as outlined in California’s Endangered Species Act (CESA). Another related development is Decision 1610, a requirement to maintain minimum streamflows. Both the CESA and Decision 1610 are significant because they support the ongoing survival of threatened steelhead trout and endangered salmon in Sonoma County (Sonoma County Water Agency, 2015). Another important act of legislation is the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), a “self-executing statute” that requires the state and local agencies to identify, and within measure mitigate, any significant environmental impacts that may result from their actions (California Natural Resources Agency, 2014). CEQA is significant because any proposal for physical development (like those relating to agricultural development) within the state of California is subject to a level of discretionary approval set forth by the legislation (California Natural Resources Agency, 2014). One critique is the lack of consideration for cumulative impact for the individual projects/proposed projects.

Evidently, there are numerous state agencies and counterpart departments that have a stake in managing California waters. In order to further enforce state legislature, 58 State counties act as formal legal subdivisions, representing the local bodies of control. The Sonoma County Water Agency is by far the most important local agency. The Water Agency, for short, exists as a separate legal entity from the County of Sonoma and was officially created by State law to provide separate flood protection, water supply and sanitation services (Sonoma County Water Agency, 2015). The Water Agency is also responsible to comply with the aforementioned federal and state regulations if it is to implement any water-related project. As outlined on their website, the Agency must comply with CEQA, the National Environmental Act (NEPA) if the project has federal jurisdiction, Section 404 permits outlined by the US Army Corps of Engineer’s wetlands regulatory program, streambed alternation agreements and permit regulations as set by the DFW, and any regulators regarding potential impacts on endangered species under the EPA for example (Sonoma County Water Agency, 2015).

Some of the more informal non-governmental stakeholders involved in water-related issues in Sonoma (beginning at a national level and working down) include: National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), National Association of Clean Water Agencies, Westcoast Watershed, Environment California, the California Landsteward Institute, and the Sonoma County Winegrape Commission. While these organizations might work alongside some of the state and regional agencies, they appear to have less holding power.

Governance Practices: Analyzing Sonoma County Water Agency

I will use Darby’s (2010) framework for governance practice to analyze transparency, accountability, and participation on behalf of one of the main agencies involved in the case study. From the outside looking in, the SCWA upholds relatively good levels of participation and accountability, but a seemingly pseudo-level of transparency.

Transparency

Transparency is defined as the “clear disclosure of information, rules, plans, processes and actions” and is legitimated by the provision of public, accessible, relevant, timely, and accurate information (Darby, 2010, p. 9). SCWA’s website has dedicated itself to outlining numerous projects, initiatives and studies that are working towards the effective management of regional water resources. External links are provided for pages outlining “projects in progress”, “recently completed projects”, “regulatory compliance standards”, “environmental documents” etc. Information, rules, and plans are clearly demarcated, organized, and made accessible to a public audience. However, there seems to be a lack of information and explicit regard for processes, and especially the relationships that bind the SCWA and wine industry stakeholders in particular development projects (a relationship which has been recorded as prevalent in other sources and anecdotal accounts).

Accountability

Accountability refers to the process of holding actors responsible for their actions (Darby, 2010). The SCWA has done a good job at setting expectations and criteria for behavior. In fact, the SCWA Community and Governmental Affairs Group is responsible for conducting community outreach programming, which primarily focuses on education and awareness, but also involves the deployment of public opinion surveys to assess the performance of state SCWA services (Sonoma County Water Agency, 2015). To make up for a lack of answerability in the investigative style survey process, the SCWA has made an effort to publicly assess the success of their current initiatives and create new strategies to secure water supply. This information can be found in the Water Supply Strategies Action Plan (Sonoma County Water Agency, 2015). I think this initiative displays a responsibility to take action when methods are not serving the public in the way that the Agency’s mission has mandated.

Participation

Participation can either be understood as consultative or empowered, depending on the level of public participation in the making of power/influence (Darby, 2010). Within the SCWA, Public Affairs staff, who manage water education and conservation, governmental affairs, and public outreach are available to meet with the community to discuss Water Agency projects. Other formal opportunities have also been created for public comment. Yet, there is little guarantee that the consultation, commentary, or opinion will be “heeded” (Darby, 2010, p. 9).

Conclusion

Overall I think the biggest concern lies with the highly structured (and dominant) nature of the state policy regime. Understanding that the decentralization of power and decision-making is largely to facilitate a functioning relationship between federal jurisdiction and localized enforcement over water, we must be weary of the bureaucratic trickle down effect. The fragmentation of some of the regulatory functions of the State and County have contributed to a discrepancy between water rights and water allocation. Grantham’s (2014) study analyses the current California water rights system, which lies at the heart of the regulation schema, and has concluded that “inaccurate water use accounting” and an over allocation of available water supplies have handicapped water policy and management in the region (p. 3-6). The inefficiency of water regulation, coupled with changing climate conditions (namely drought) has perpetuated a staggering uncertainty of water use and withdrawal. The key to improving the State and County’s joint capacity to properly enforce the legislation that has been created, is to create a more cohesive dynamic between the two entities, and to also improve the quantification, measurement, and regulation of important regulatory functions (i.e. water rights).

Bibliography

Darby, S. (2010). Natural resource governance: new frontiers in transparency and accountability. London. Accessed 26 October 2015 at http://www.transparency-initiative.org/reports/natural-resource-governance-new-frontiers-in-transparency-and-accountability

Department of water resources (DWR). (2014). Water planning. Accessed 27 October 2015 at http://www.water.ca.gov/planning/

Gleick, P, H. (2003). Global freshwater resources: soft-path solutions for the 21st century. Science 302 1524–8

Grantham, T., & Viers, J. (2014). 100 years of california’s water rights system: Patterns, trends and uncertainty. Environmental Research Letters, 9(8) doi:10.1088/1748-9326/9/8/084012

Hanak, E., Lund, J., Dinar, A., Gray, B., Howitt, R., Mount, J.. . Thompson, B.(2011). Managing california’s water: From conflict to reconciliation. (San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California)

Lall, U. (2013). Why aren’t we getting our money’s worth from our water infrastructure. Growing blue. Accessed 27 October 2015 at http://growingblue.com/blog/future/why-arent-we-getting-our-moneys-worth-from-our-water-infrastructure/

Littleworth, A, L., Garner, E, L. (2007). California water II. (Point Arena, CA: Solano Press Books)

Sonoma county water agency. (2015). Current Projects. Accessed 25 October 2015 at http://www.scwa.ca.gov/compliance/

United states environmental protection agency (EPA). (2015). Water enforcement: Clean water act compliance monitoring and assistance. Accessed 26 October 2015 at http://www2.epa.gov/enforcement/water-enforcement#cwacompliance

United states environmental protection agency (EPA). (2015). Summary of the clean water act. Accessed 26 October 2015 at http://www2.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act

UN-Water Work Programme 2014-2015. (2015). UN-Water Governance. Accessed 29 October 2015 at http://www.unwater.org/fileadmin/user_upload/unwater_new/docs/UN-Water_Work_Programme_2014-2015.pdf

UN-Water Strategy 2014-2020. (2014). UN-Water Governance. Accessed 29 October 2015 at http://www.unwater.org/fileadmin/user_upload/unwater_new/docs/UN-Water_Strategy_2014-2020.pdf

U.S. fish and wildlife service: Endagered species. (2013). Federal agencies programs. Accessed 27 October 2015 at http://www.fws.gov/endangered/what-we-do/federal-agency-programs.html

Water board (State water resources control board). (2014). The water rights process. Accessed 29 October 2015 at waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/board_info/water_rights_process.shtml

General Agency Websites (see above for specific articles):

http://www.calepa.ca.gov/About/

http://www.californialandstewardshipinstitute.org/

http://environmentcalifornia.org/cae/about

http://www.habitat.noaa.gov/index.html

http://www.nfwf.org/whoweare/Pages/home.aspx#.Vi1TphCrSHo

http://www.swrcb.ca.gov/about_us/