Introduction:

Have you ever thought about the work that goes into creating a crop plan, or do you think gardening is simply planting and harvesting what you want to eat?

Well, it turns out that there is more to it than what meets the eye. Over the past few weeks, we have learned about the logistics of urban crop planning on a semi-large scale. There were numerous factors that we had to consider when planning crops for the Gordon Neighbourhood House (GNH), such as companion planting, crop rotation, sunlight availability, and amount of time/resources required to care for the individual crops. It is important to take all of these factors into account and determine the most suitable seeds to plant in the unique conditions of each individual sites. It was definitely a hard task, but we have learned to appreciate the work that farmers put in to harvest organic produce for the community!

Check out our Proposal Report for our project!

Weekly objectives:

It has been about a month since our initial visit at the GNH, and our group has had a number of objectives for the project during this time. Our weekly objectives since our first visit at the GNH are as follows:

Jan. 21 – 27: Research and learn about the GNH and the West End Community before beginning our project. Complete our first draft of the first blog post.

Jan. 28 – Feb. 3: Edit and rewrite our blog post to suit the requirements of the assignment. Begin planning the Proposal Report for the project by creating an outline.

Feb. 4 – Feb. 10: Reconfigure the Proposal Report upon receiving comments and advice from our TA and classmates, and hand in a final draft. Additionally, visit the GNH and begin working with Joey.

Feb. 11 – Feb. 17: Plan out the timeline of the project for the rest of the term.

Feb. 18 – Feb. 24: Write our second blog post.

Achievements:

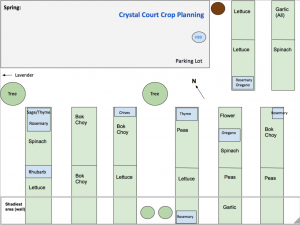

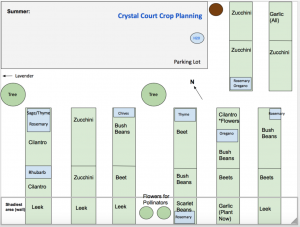

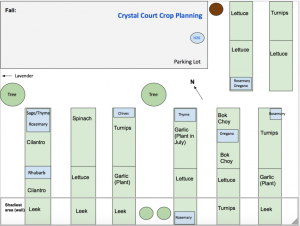

One of our biggest achievements so far is the completion of one of the three crop plans, for the Crystal Court location. This location is the largest and most complex out of the three due to the fact that it receives the most sunlight. As a result of the sun intensity, the more difficult (sun-loving) crops needed to be planted in this location, such as zucchini, beans and greens. Most of the sun-loving crops are considered to be summer crops and require a greater degree of care and time. While other crops can be grown for the first or second half of the growing season (spring and fall crops, respectively), summer crops take up the majority of the growing season (J. Liu, personal communication, February 15, 2018). Furthermore, these crops are the highest in demand for the kitchen and farmers’ market, so Joey wanted to emphasize growing as much of these as possible. We finalized the outline for the spring, summer, and fall seasons following Joey’s list of highly requested crops. To complete this task we needed to take into consideration what had been grown in the previous few seasons and choose different, complementary crops for a crop rotation scheme. We also included companion planting into the plans to maximize beneficial interactions between the crops. We managed to complete crops for all three seasons for this location in one meeting and it was beyond rewarding to finalize the plan. It served as a guideline for what to expect for the other locations, and it was good to see all of the implications for making sure the crops we choose thrive, not only as individual crops, but in conjunction with their surroundings and across seasons.

Spring crop plan for Crystal Court garden

Summer crop plan for Crystal Court garden

Fall crop plan for Crystal Court garden

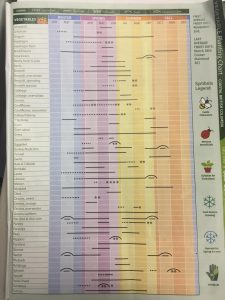

Some resources that we used in planning which crops we planted, as well as when and where we planted them

Gardening and urban farming is often associated with the well-off, white, middle class, being included in the alternative food narrative (Slocum, 2007) that was di discussed in session 8. This gives the essence of our project a sense of privilege, despite the fact that the GNH works to serve the vulnerable and underprivileged people in its community. We believe that the GNH does a good job of using urban agriculture to serve its entire community through its food philosophies overall (Gordon Neighbourhood House, n.d.), although there are still aspects of this that we must think critically about.

We were glad to learn from Joey, the head farmer at GNH and an Asian female, that people of different races have been actively participating in the community garden program. However, very few low-income people are involved in the program, mainly due to their lack of time. It should be noted that low-income families make up a staggering 32.8% of the West End community (City of Vancouver, 2012). Single mothers are also often excluded due to the burdens of poverty and raising kids. This situation is discussed in Miewald & Ostry’s (2014) article that we read in session 4, which states that time and money are both barriers that prevent people with lower incomes from accessing healthy food or the resources to provide them with food aid.

The Gordon Neighbourhood House tries to address this issue through the implementation of food initiatives such as the community lunch program and affordable farmers’ markets as a way to serve people who lack the time to cook or access to nutritious food. However, it is not clear to us whether this has successfully addressed this issue, because these pay-what-you-can community meals and farmers markets are still very Western practices that might not be welcoming to people of colour, as discussed in Gibb and Wittman’s paper (2013) that we read for session 8.

As mentioned in our first blog post, through assisting the GNH in establishing a successful crop plan and preparing its urban farm plots, we originally aimed to contribute to its efforts in decreasing food insecurity in marginalized people such as low-income people and people of color, thereby increasing the overall community food security of the West End. However, as we realized that food injustice might not be effectively addressed by the GNH’s initiatives, we are wondering how influential our project will be in contributing to community food security. These have been some “sticky” moments for us as a group, and hopefully, we can gain some clarity on these issues as the term goes on by further discussing them with our community partner, doing research and spending more time unpacking these issues in lectures and tutorials.

Moment of significance:

Our group’s first moment of significance this term came upon receiving comments and suggestions for our Proposal Report from our TA and classmates. As we were writing our first draft of our outline for this report, we were focusing on examples provided in lecture and tutorial, and tried to integrate aspects from class readings and past class materials. We ended up establishing objectives that were far too broad and idealistic for a project of our size and timeframe. This translated into our methods being unfocused and vague, and gave the proposal an overall sense of ambiguity.

What:

Some of the components that we tried to integrate into our proposal outline included food sovereignty, food literacy, and community food security. For example, we tried to come up with links to food literacy and planned on conducting surveys to get a better idea of the degree of food insecurity in the West End, as well as how much food insecure residents of the West End were truly benefiting from the services provided by the GNH. This is because we saw that a lot of other groups were planning on conducting surveys and focusing on food literacy. However, our TA, Colin pointed out to us that this might be a bit too much to address in our project, and that conducting those surveys wouldn’t directly relate to our objectives. Most importantly, we were losing focus on the main purpose of our project, which was to come up with a crop plan that would increase the community food security of the West End.

So What:

Since we did not realize that our project was quite specific and straightforward compared to many other groups’, we incorporated many concepts relating to the food system into our project originally. Writing the proposal report was crucial in helping us realize that our goals were too broad and impractical. By reflecting on our duties in this project, which came down to assist in the design of a crop plan for three garden sites. We were able to narrow down our objective to performing a site assessment of the three sites to create feasible crop plans. If we had continued with our original objectives and goals, we would have been too focused on food literacy and surveying to dedicate enough time to actually creating the crop plan, prepping the farm sites for gardening, and considering how our project can contribute to community food security. This moment of significance provided us with a clearer understanding of our project and trajectory, hopefully leading to a more efficient execution of the project and ultimately helping us obtain better results. It also gave us a greater sense of motivation and inspiration in proceeding with the actual tasks of the project. This moment of significance gave us an opportunity to “catch and release” in terms of our perspectives and abilities, and helped us come to a better understanding of how we should be applying what we have learned in lectures and tutorials.

Now What:

Through our completed proposal report, we have simplified our project to focus on planning crops for GNH’s three urban farm sites in the West End. Appropriate design is essential in order to minimize external inputs and maximize outputs, so we will continue to do research for our remaining two gardens, which have different surroundings and growing conditions than Crystal Court. We plan on scheduling a few more meetings with Joey in the coming weeks to complete the last two crop plans with inputs and guidance from her. We can use our experience working on the Crystal Court crop plan to help us stay on track and fixate on what’s important when designing the remaining crop plans. Additionally, meeting with Joey will give us an opportunity to gain more insight on how the urban farms provide value and benefits to the West End, especially as the growing season nears and preparations begin. At the end of the term, our group will be partaking in the preparation of the gardens ourselves, which will give us an inside perspective on the physical work that goes into preparing urban farm plots.

Upcoming Objectives

We are planning on visiting the Gordon Neighbourhood House during our final Flexible Learning Session on March 6th to continue working on the crop plans. We hope to complete the crop plans for the remaining two locations (Jervis & Nicola plots). We also plan on visiting some of the community gardens to harvest some winter crops and begin preparing the plots for the upcoming growing season.

Conclusion

As a result of our moment of significance, we have shifted our focus for our CBEL project. That is, developing the crop plans themselves in order to improve community food security rather than trying to integrate too many food system concepts from lectures into our project, which would ultimately make our scope too broad and impractical. While working on the crop plans, our group is also gaining an understanding about the amount of thought that is required to develop a crop plan that fits within the specific conditions of each farm site, and extraneous factors such as sunlight availability, companion planting, and the amount of care needed by specific crops. We have completed our crop plan for the Crystal Court location, which is the largest and most complex location. We are looking forward to working on the remaining two crop plans with Joey’s input and hopefully getting some hands-on experience by helping to prepare the gardens ourselves for the upcoming season!

While working on this project, we’ve also started to uncover some issues of race, gender, and class that are prevalent in the food system, which we are simultaneously learning about in the course. We recognize that there is an air of privilege surrounding our project, as alternative food movements such as urban farming tend to only include the well-off middle-class people and underprivileged people are not able to partake for various reasons (Slocum, 2007). In addition, although the GNH’s food philosophy and programs intended to serve and benefit the West End community as a whole, predominantly the marginalized groups present, the reality is that some low-income individuals do not have the resources needed to be able to participate in the community garden program (Miewald & Ostry, 2014). We hope to keep these issues in mind and gain more clarity on them as the project proceeds, and to find ways to address and mend them as a group.

References:

City of Vancouver (2012). West End: exploring the community. Retrieved from http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/profile-west-end-2012.pdf

Gibb, N., & Wittman, H. (2013). Parallel alternatives: Chinese-Canadian farmers and the Metro Vancouver local food movement. Local Environment, 18(1), 1–19.

Gordon Neighbourhood House (n.d.). Food philosophy. Retrieved from https://gordonhouse.org/about-gordon-neighbourhood-house/right-to-food/

Miewald, C., & Ostry, A. (2014). A Warm Meal and a Bed: Intersections of Housing and Food Security in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Housing Studies, 29(6), 709–729.

Slocum, R. (2007). Whiteness, space and alternative food practice. Geoforum, 38(3), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEOFORUM.2006.10.006