In her memoir Missing Sarah: A Memoir of Loss, Maggie de Vries tells the story of Sarah de Vries, her adopted sister, by sharing journal entries, family history, and the stories of those who had known Sarah throughout her life. Sarah de Vries was a sex worker, drug addict, and one of the missing and murdered women who had disappeared from the Downtown Eastside in the late 1990s. Through a slow investigation process, the Vancouver police department discovered that the many women who had disappeared in the Downtown Eastside were killed by Robert Pickton, a serial killer who lived in Port Coquitlam, BC. Pickton brutally murdered these women, and ultimately faced twenty-six first degree murder charges, although he was only convicted of six. Serial killers are often associated with antisocial personality disorder, a psychological disorder that many convicted criminals who have committed the most heinous crimes have been diagnosed with. De Vries gives Sarah and other silenced sex workers and drug addicts— people society discards as unworthy— a voice. The question I ask is what voice sociopaths, in other words, those suffering from antisocial personality disorder, have in life writing when societal stigmatization interferes with their self-representation just as it does with missing and murdered women.

Antisocial personality disorder is a mental illness where a person lacks a conscience and consequently appears host to many “evil” qualities. For example, people diagnosed with this disorder seek power and manipulate people with cunning charm and wit to acquire that power (Mayo Clinic). They are indifferent to right and wrong, pathological liars, unempathetic, hostile, and impulsive (Mayo Clinic). They have a tendency to partake in criminal behaviour and a tendency to perceive themselves as superior to others (Mayo Clinic). Psychologists have speculated over how this illness develops for decades, and they have arrived at two hypotheses. The first hypothesis is that sociopaths do not experience fear as everyone else does, and hence pursue their illegal and inappropriate behaviour unfazed by the threat of punishment (Lilienfield). The second hypothesis is that sociopaths tend to be underaroused, and in order to achieve emotional stimulation they pursue actions that create excitement (Lilienfeld).

Regardless of the symptoms and causes of this mental disorder, there are limited resources available to understand this illness, as many suffering from this illness have not represented themselves in a personal narrative. However, I managed to find one memoir that proves a testament to sociopaths. Psychology Today actually features excerpts from M.E. Thomas’ The Confessions of a Sociopath: A Life Spent Hiding in Plain Sight, a memoir that chronicles the experiences and thoughts of a successful lawyer who has been diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder. Reading these passages, there are many alarming aspects of the author’s emotional state that emerge, but at the same time, there are various positive qualities that emerge as well. Her blunt vulnerability and intimacy are very powerful tools employed in the following excerpts:

“An image sprang to mind: my hands wrapped around his neck, my thumbs digging deep into his throat, his life slipping away under my unrelenting grasp. How right that would feel.”

“Do you ever find yourself using charm and confidence to get people to do things for you that they otherwise wouldn’t? Some might call it manipulation, but I like to think I’m using what God gave me.”

“The only physical contact I sought usually entailed violence. The father of a friend in grade school had to pull me aside and sternly ask me to stop beating his daughter. She was a skinny, stringy thing with a goofy laugh, as if she were asking to be slapped. I didn’t know that I was doing something bad. It didn’t even occur to me that it would hurt her or that she might not like it.”

“The first recurring dream I can remember was about killing him with my bare hands. There was something thrilling about the violence of it, smashing a door into his head repeatedly, smirking as he fell motionless to the floor.”

“I stole from the lost and found, saying I lost a book, but then I would take the “found” book to the bookstore and sell it. Or, I’d take an unlocked bike that sat in the same place for days. Finders, keepers.”

“I am an accomplished attorney and law professor, a well-respected young academic who regularly writes for law journals and advances legal theories. I donate 10 percent of my income to charity and teach Sunday school for the Mormon Church. I have a close circle of family and friends whom I love and who very much love me.”

“I think my sociopathy was triggered largely because I never learned how to trust.”

“Everyone is a sinner, and I never felt that I was outside this norm.”

“But I am functionally a good person—I bought a house for my closest friend, I gave my brother $10,000, and I am considered a helpful professor. I love my family and friends. Yet I am not motivated or constrained by the same things that most good people are.”

Ultimately, the reader receives personal qualities that society would sort into either positive or negative categories from Confessions of a Sociopath. Though Thomas manages to humanize herself, albeit slightly, midst many of her demonic qualities, I fear that readers, because of the work of publishing companies, will focus on the negative conduct she documents within her memoir with the same reverence that people pursue a psychologically thrilling movie or novel. In her article “Introduction: Word Made Flesh,” Gillian Whitlock discuss how autobiography is a “soft weapon.” “Softness” implies malleability, and in regards to autobiographies, malleability is created by publishing companies that use “a careful manipulation of opinion and emotion in the public sphere” (3) to develop the viewpoints of an audience. G.T. Couser, in his article “Rhetoric and Self-Representation in Disability Memoir,” describes how the disabled “may be granted access to the literary marketplace on the condition that their stories conform to preferred plots and rhetorical schemes” (33). Schaffer and Smith, in their article “Conjunctions: Life Narratives in the Field of Human Rights,” discuss how human rights life narratives are dependent on “a Western-based publishing industry, media, and readership…[which] affects the kinds of stories published and circulated, the forms these stories take, and the appeals they make to an audience” (11). Though these scholarly articles are not referring to mental health life narratives, they make it clear that publishing companies attempt to create stories that appeal to a certain audience. In today’s world, a fascination for evil proliferates in the televisions shows we watch, the video games we play, and the books we read. I did not read Confessions of a Sociopath in its entirety, so I am not aware of how exactly M.E. Thomas was portrayed for the most part. I am certain that she presented herself without regard to societal expectations because of her mental state, but I recognize that editing is a form of enhancement. Hence, there remains a degree of uncertainty to how accurately these writers will be able to represent themselves amid publishing companies who are primarily interested in profit.

I am not saying that we should sympathize with Robert Pickton, but I believe there is a purpose in highlighting the fact that sociopaths are also a silenced people. Mental illness is still stigmatized in today’s world, but we do see more life narratives emerging from people who have suffered, for example, from depression, schizophrenia, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. To better understand people and the world around us, we need to be open to hearing the many perspectives of every citizen, sociopaths and all, because fundamentally we are all human. Altogether, we must be wary of how societal standards continue to shape our perceptions.

“Antisocial Personality Disorder.” Mayo Clinic, 2 April 2016, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/antisocial-personality-disorder/symptoms-causes/dxc-20198978. Accessed 20 November 2016.

“Confessions of a Sociopath.” Psychology Today, 9 June 2016, https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/201305/confessions-sociopath. Accessed 20 November 2016.

Couser, G. Thomas. “Rhetoric and Self-Representation in Disability Memoir.” Signifying Bodies: Disability in Contemporary Life Writing. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan UP, 2009. 33.

De Vries, Maggie. Missing Sarah: A Memoir of Loss. Toronto, Penguin, 2008.

Lilienfeld, Scott, et al. Psychology: From Inquiry to Understanding. New Jersey, Pearson Education Inc., 2016. Print. 594-595.

Schaffer, Kay and Sidonie Smith. “Conjunctions: Life Narratives in the Field of Human Rights.” Biography 27.1 (2004): 11. Print.

Whitlock, Gillian. “Introduction: Word Made Flesh.” Soft Weapons: Autobiography in Transit. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. 3.

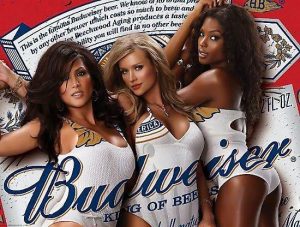

nted as possessions of men in advertisements. It is not unusual for a woman to be presented as the actual bottle of alcohol or the actual car being advertised. By turning women into “things” and “objects” Kilbourne describes how a situation is created where women are stripped of character and subjective experience, hence promoting violence against women. She goes on to illustrate how ads feature women with their hands covering their mouths and how ads force women to adopt other passive and vulnerable poses that make it seem as though they exist only for men, that they need to be taken care of by m

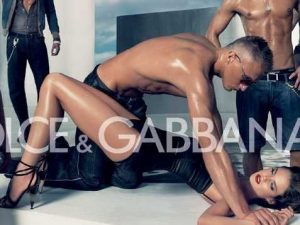

nted as possessions of men in advertisements. It is not unusual for a woman to be presented as the actual bottle of alcohol or the actual car being advertised. By turning women into “things” and “objects” Kilbourne describes how a situation is created where women are stripped of character and subjective experience, hence promoting violence against women. She goes on to illustrate how ads feature women with their hands covering their mouths and how ads force women to adopt other passive and vulnerable poses that make it seem as though they exist only for men, that they need to be taken care of by m en, and that they cannot be independent. This provides a possible explanation as to why society so often refers to women in context to men. Kilbourne also uncovers how the increased presentation of violent images within the media, presenting men as powerful and dominant, connects masculinity with violence and desensitizes society towards violence, influencing people to blame victims and sensationalize violent acts.

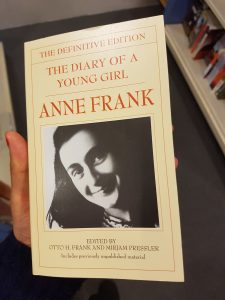

en, and that they cannot be independent. This provides a possible explanation as to why society so often refers to women in context to men. Kilbourne also uncovers how the increased presentation of violent images within the media, presenting men as powerful and dominant, connects masculinity with violence and desensitizes society towards violence, influencing people to blame victims and sensationalize violent acts. u and be happy” (Frank, 7 March, 1994), her optimism secures contentment and peace within her heart, reinforcing her happy personality. Red appears to be suggestive of passion, love, and courage, but also depicts danger (Colour-meanings.com). Anne is in a perilous situation, but she manages to face the challenging circumstances with strength and ferocity. She describes it herself: “I know what I want, I have a goal, an opinion, I have a religion and love. Let me be myself and then I am satisfied. I know that I’m a woman, a woman with inward strength and plenty of courage” (Frank, 11 April 1944). Altogether, the colours utilized on the cover of the text permit the reader to establish conclusions on the context of the narrative– particularly the young writer’s character– without even reading the text itself.

u and be happy” (Frank, 7 March, 1994), her optimism secures contentment and peace within her heart, reinforcing her happy personality. Red appears to be suggestive of passion, love, and courage, but also depicts danger (Colour-meanings.com). Anne is in a perilous situation, but she manages to face the challenging circumstances with strength and ferocity. She describes it herself: “I know what I want, I have a goal, an opinion, I have a religion and love. Let me be myself and then I am satisfied. I know that I’m a woman, a woman with inward strength and plenty of courage” (Frank, 11 April 1944). Altogether, the colours utilized on the cover of the text permit the reader to establish conclusions on the context of the narrative– particularly the young writer’s character– without even reading the text itself. ook includes details that other readers do not have access to almost seems to mirror the idea of gossip (NPR). By manipulating the human folly of love for gossip, the capitalized statements compel the consumer to purchase the autobiographical text, because gossip, or “being in the know,” tends to garner a sense of belonging and social security that humans crave. By using this technique, publishers secure profits by making the book enticing, and therefore marketable.

ook includes details that other readers do not have access to almost seems to mirror the idea of gossip (NPR). By manipulating the human folly of love for gossip, the capitalized statements compel the consumer to purchase the autobiographical text, because gossip, or “being in the know,” tends to garner a sense of belonging and social security that humans crave. By using this technique, publishers secure profits by making the book enticing, and therefore marketable.