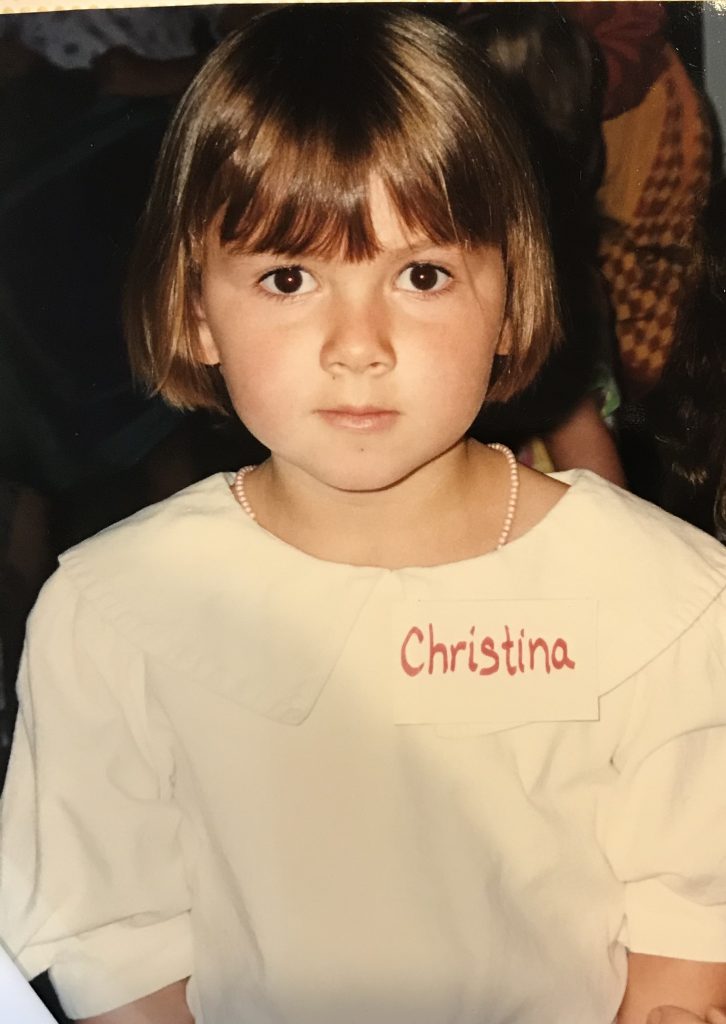

Post by Christina Mantey

This post is one in a series of five blog posts written by Christina Mantey, a research assistant on the Conceptualizing Recordkeeping as Grief Work (CRAGW) project. Christina has an interesting perspective on the emotional (and sometimes trauma-related) dimensions of archival work, having come to the field from a career in nursing. This series of blog posts is a personal account of her work as a research assistant with the CRAGW project and of her journey as a second-career archival graduate student.

Part 1: How to Succeed (and Fail) in School

I am an outlier in this field, though I doubt you would notice. I’m different in the same way you find out your friend Kathy from the gym was actually born in Norway when you finally hang out outside of aerobics class. I’m unique in a subtle way, but in a way that makes how I view archiving different from my peers.

Just like the rest of my cohort, this spring I will graduate from the University of British Columbia’s School of Information and will receive a Masters of Archival Studies and a Masters of Library and Information Science. As budding professionals in information fields, we love delicate old books, obscure historical facts, and meticulously organized… anything. We were suckers for the bookbinding activity in our Preservation class and field trips down to UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections. As a unique discipline tucked away inside the facade of an old stone library on the sprawling grounds of UBC, we sought out our similarities and delighted in our individuality with the zeal of a Hogwarts house.

However, after rejoicing in our uniqueness as a group, our individual differences became more apparent. For example, I’ve realized that few in this field have handled narcotics or seen dozens of people naked. (Perhaps a few have, but I’m betting on less than ten percent.)

This difference became clear even from my first day attending UBC in 2018. As our gaggle of new students nervously chatted while huddled outside the doors before our first class, I discovered many of my peers were freshly out of undergrad, most having received degrees in the humanities. They were bright and cheerful and excited for a new beginning; hopeful in a profession in which they had entrusted their future. They reminded me of myself five years previously when I graduated with a degree in nursing and began my first job at a hospital.

I never fantasized about becoming a nurse as a child. Or as a teenager. Or as an undergraduate student. I fell into nursing because there wasn’t anything stronger to fix upon. Though I sampled a variety of subjects throughout my undergraduate career — from Ancient Greek to Gender and Women’s Studies — there were no other subjects I felt strongly enough about to settle on as a major. I enjoyed science and social sciences and I had friends who were applying to the reputable nursing program within the college, so why not also apply and see what happens?

After I was accepted into the nursing program I rationalized away my lurking apathy for the profession. Nursing was practical: I could get a well-paying job anywhere right out of school. Nursing required knowledge in many subjects I found interesting: biology, anatomy, psychology, sociology. Nurses enjoy an active work life: they have lots of interaction with different people and aren’t stuck behind a desk all day. The panicked sinking feeling that resurfaced when I thought about a decades-long nursing career could be easily covered over with these pretty, plastic-y assurances; like a Disney Princess Bandaid over an infected bite.

I successfully ignored my trepidation and did well in the nursing program. I was used to achieving in school as I was an anxious rule-follower who wanted nothing more than to please my instructors.

For example, at the age of five, I made my kindergarten teacher construction paper ladybugs every day at craft time because she once mentioned she liked ladybugs. Eventually, she had to gently suggest I make creations for the other students so she could fend off the growing swarm of sticky, lopsided insects. I’ve been making figurative construction paper ladybugs for teachers ever since — usually manifesting in the form of well-studied-for tests and perfectly rubber-cemented tri-fold project boards.

My studious approach to school continued for my nursing degree. At the end of my senior year, I received the honour for academic excellence and presented research at a conference in Chicago. I assumed that because I was good in school I would be equally excellent in the workplace.

This was partially true, but mostly not. I did eventually become proficient but only after months of floundering and desperate pleas for help from other nurses. I quickly realized my nursing program had been heavily focused on theory and less so on practical skills and hands-on experience. In our nursing clinicals we would watch our precepting nurse and study their cases as they rushed to perform their nursing duties. This gap in training became apparent as soon as I passed my boards and — bright-eyed and bushy-tailed — began a job at the local hospital.

I watched as the other new grads who had been hired with me seemed to know exactly what to do — from getting reports from outgoing nurses to understanding the surprisingly complicated process of taking patients to the washroom. I was stung by the harsh momentum of my new job. I was no longer in my safe, academic sphere where there was time to mull over a medical case and discuss hypotheticals. In my academic career, people were always cordial, respectful, and at the very least, polite. Paper ladybug, anyone? I’ll promise to make you one every day if you smile and give me a pat on the head.

There were no ladybugs in the hospital. I soon found my new day-to-day was a battle zone complete with blood, guts, and death and where people yelled at you even if you were nice to them. This is where I would spend my days for the next four years.