Write a blog that hyper-links your research on the characters in GGRW according to the pages assigned to you. Be sure to make use of Jane Flicks’ GGRW reading notes on your reading list.

Northrop Frye, the quintessential mid-twentieth century Canadian literary critic, has found himself unknowingly and posthumously playing an integral part in the literary resistance permeating Thomas King’s novel, Green Grass, Running Water. Frye, both in his philosophy and his historical personality, comes to represent the Colonial status quo that King dismantles on route to helping us envisage alternate readings of our history and our stories. I am not just speaking about the character Joe Hovonaugh , who is inspired by Frye (Chester, 50), but of the novel’s structure in its entirety. The book itself, its fundamental way of being, is a stark contrast, if not a direct challenge to the literary world established in Frye’s writings. As Bianca Chester clearly explains, Frye was a structuralist who believes that meaning text is always confined to world of literature and thus has “less to say about the outside world than it does about something called “literariness.”(Chester, 50). King completely challenges this role of literature. He tells stories where history, politics, and mythical narratives live as equal partners. The paper acts as a meeting point, a bridge, a safe space where fiction and fact can share a bedroom without the truth police breathing down their necks. The division of labour is absolute, even the reader has a role to play. While, at times, his book reads with passive ease of a harlequin novel, it quickly becomes clear that a little more effort will go a long way. Important pop- culture references, political satire, Indigenous knowledge and historical allusions, are planted like seeds throughout the pages and with the necessary doses of curiosity and diligence the meaning and importance of the text grows exponentially.

In the following paragraphs, we will journey as engaged readers through ten pages of King’s novel and take the time to uncover the stories that lay beneath the story. Herein lies the essence of what Chester calls the “dialogic” meaning making in King’s text (Chester,47) By layering the story, King begins conversations at all levels which puts distinct parts of the puzzle in active dialogue. The reader is in dialogue with the author, realist narratives are in dialogue with mythical ones, history is in dialogue with popular culture, and literariness is in conversation with the ‘real’ world.

Pgs 212-222 (1993 edition)

Disney, Pocahontas and Indian Industry

At the beginning of this section in the book we are located in Los Angeles, amidst the return of Charlie and his father, Portland, to Hollywood. Following the passing of his wife, Portland (whose name is also that of largest city in Oregon ,a relevance I have yet to ascertain), has brought his son with him to the capital of the film industry as he tries to revive his latent acting career. Instead of the jumping back on to the big screen, however, Portland finds himself working in a strip club called “Four Corners” playing the token angry and belligerent savage who first intimidates the innocent Pocahontas and then seduces her with his wild antics (King 212).

The name of the club itself, Four Corners, is , as Jane Flick points out, a darkly satirical allusion to a place, in the southwestern United States, where Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado meet and which is of significant cultural import to Native Americans (Flick 158). The sad irony being that in the burlesque club the patrons are entertained by a dance that highlights the racist, Eurocentric, and deeply offensive portrayal of Indigenous people/culture in mainstream media. Pocahontas, the main erotic draw of the show, is based on the historical figure that Disney has made famous (in their movie of the same title) that depicts a romanticized image of the savage princess whose super-model figure and wild beauty is a prize to be won by conquering European settlers. Even in current American politics the name Pocahontas has taken on a life of its on and been used to demean and ridicule female politicians associating with their Indigenous heritage

Of course, the strip club is only one example of King’s major fascination with the media’s (and specifically film’s) historical representation of Indigeneity. After Four Corners, we return to Portland’s home where we (re) encounter Portland’s old friend C.B Cologne , who is Italian and also has played many of the “Indian” leads in the classic Westerns. Cologne’s name is a cynical nod at Christopher Columbus (his Spanish name was Colon) who is famous for being the first explorer to “discover” America (Flick 153). The reference to Columbus seems to draw our attention to the way Europeans , echoing the way the Columbus erroneously gave them their name based on his own narratives, have manufactured (in no small part through film) an image of the “Indian” to fit with their perspective of reality.

Alberta is Alberta Frank and Old is New

In the next few pages we skip to the realist storyline involving Alberta Frank and her continued struggle to decide how to have a baby without involving a man. Alberta’s name is an obvious reference to the Province that much of the novel rotates around. It is also suggested that her last name, Frank, might either refer to her “frank” personality or ,alternatively, to the deadly rockslide in Frank, Alberta in 1903. While the rockslide connection is interesting and adds another layer of possible dialogue (the relationship between individual people and larger historical events), I find myself more interested in the conversation between the Alberta, the Province and Alberta, the person. The Province of Alberta is home to the Blackfoot as well as some of the most stunning natural landscapes but it is also home to modern industry that is devastating the land at an alarming rate. In Alberta, the character, there is also this contradiction, the wrestle between worlds. This desire to move forward, to birth the next generation but a simultaneous fear of the masculine energy (which some might also associate with resource extraction) that threatens to mess it all up.

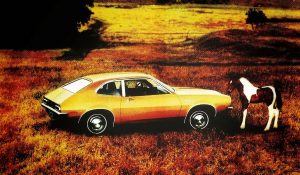

In this same section Alberta imagines Charlie mounted on a pinto “ briefcase in one hand, the horse’s mane in the other, his silk tie floating behind him” (King 214). The pinto horse is of significance because they are closely associated with the “painted” ponies that are depicted in Cheyenne paintings at Fort Marion but are also a make of Ford car that features in the novel ( Bobo’s and eventually Charlie’s rental) (Flick 146) . The juxtaposition of horse and car echoes King’s theme of the overlap and possible tensions between traditional and modern (Western) ideals.

Next, we return to Lionel watching a Western on TV (the same Western that everybody seems to be watching that night in Blossom, Alberta). However, the film does not run its normal course. Pushing the boundaries between fiction and fantasy, King interjects non-rational occurrences in to his realist narrative. First off, “four old Indians” are seen in the movie, waving their lances on the banks of the river with one “wearing a red Hawaiian shirt” (King 216). The old “Indian” are the same four escapees from the asylum in Florida . They take on different names during the novel but they are quite clearly representing the seventy- two native Americans who (see Cheyenne paintings at Fort Marion above) were captured and held captive for nothing more than being “Indian”. As Marlene Goldman mentions , the novel’s reference to the Fort Marion prisoners ,”serves as a formal and thematic touchstone that highlights the challenge of the novel to the imposition of non-Native boundaries and enclosures and, more generally, to European modes of mapping.” (Goldman 21) By placing these four characters inside a traditional ‘Cowboy Western’ with the likes of John Wayne and Richard Widmark, King is forcibly disturbing these boundaries and demanding that we dialogue with the narratives that these films are perpetuating. In turn, the presence of the “four old Indians”, who are also representing the Cayote-Trickster transformers of Indigenous culture, signals the start of a total reclamation of the Hollywood story which ends later in the book with a successful Indigenous revolt (stunning all the viewers who cannot believe that a movie they know should end one way, does not).

Dr. Evil?

The final sub plot of this section is that involving Dr. Joe Hovaugh, the director of the prison/asylum at Fort Marion, who is obsessed with re-capturing his escaped inmates. The doctor is a character that plays and converses on many levels. To begin, his name is a clear word play on Jehovah, which might be away for King to highlight the Christian narratives that played a large role in Colonial worldviews. Going deeper into the character of Hovaugh, however, it has been understood that King modeled him off Northorp Frye and his ‘closed system’ approach to literature and the world (Chester 49). Coming full circle with the opening paragraph of this blog, we see how King uses literature and story as a space for conversation. He challenges Frye, not by arguing with him directly, but rather by telling stories that hold characters, allusions and references that clearly break down the walls that Frye was convinced existed between t literature and the world outside.

Works Cited

Chester, Blanca. “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel.” Canadian Literature 161-162. (1999).Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Flick Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Fox, Jana. Tricksters As Transformative Teachers. Transformative Educational Leadership Journal, 2017. Web. 15 Mar. 2019

“Four Corners Region Geotourism Map”. National Geographic. Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Gale, Thomson. “Christianity And Colonial Expansion In The Americas”. Encycolpedia.com, 2007. Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Goldman, Marlene. “Canadian Literature: Mapping and Dreaming: Native Resistance in Green Grass, Running Water”. University of British Columbia Press, 1999. Web. 14 Mar. 2019

King, Thomas. “Green Grass Running Water”. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Morton, Ellen. “The Dramatic Remains of Canada’s Deadliest Landslide“. Slate, 2014.Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Poc, Nerdy. “Examining Racist Tropes In Disney Animated Films“. Medium.com, 2017. Web. 14 Mar. 2019

“Pinto Horse“. Petguide.com. Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Sachs, Honor. “How Pocahontas — the myth and the slur — props up white supremacy”. Washington Post, 2018.Web. 15 Mar. 2019

Image

Hurd, Dennis Sylvester. “1971 Ford Pinto Print Ad“. Flickr, 2018. Web. 14 Mar. 2019

Hi Laen,

I really enjoyed reading your post analyzing the connections between King’s writings and his use of allusion. I was particularly struck by the ways you discussed how King engages with old and new media in his criticism of the representation of Indigenous peoples. Your comparison of the strip club and the Western movie really made me think about how King uses multimedia and real-life examples to demonstrate the pervasiveness of negative stereotyping of Indigenous peoples. I also really appreciated your analysis of the Four Corners name — this was a reference that went a bit over my head in my initial read, so learning the significance of the location really enriched my reading and helped me discover more depth to the text. I had initially wondered if the Four Corners name might also be related to the medicine wheel and it’s four quadrants, which are also related to the text as a whole. I think the possible layers to this name is just one example of the ways King incorporates hypertextuality and extra-textual work into his writing.

You mentioned the irony in this name, but I was wondering if you think this could also be read as highlighting the objectification of Indigenous peoples and bodies, in particular? Given the nature of a strip club, this objectification also makes Portland a participant in this objectification; why do you think King chooses this particular setting for emphasizing Portland’s limited options as he attempts to reignite his film career?

Hi Charlotte

Thanks for digging deeper into my post. You bring up a really interesting second layer to the “Four Corners” reference that I did not discuss, the idea that it also can speak to Indigenous concept of the medicine wheel. This helps to reinforce the ironic juxtaposition of meaningful cultural references with demeaning cultural representations. Your articulation of the strip club scene as the “objectification of Indigenous peoples and bodies” was exactly where I was going in my reading.

To answer your question, upon reading Kevin Hatch’s most recent blog (https://blogs.ubc.ca/kevinhatch/) I came to see that Portland, in name and action, as representing the “Americanization” of Indigenous culture. The character of Portland was tragically addicted to Hollywood and was unable to see his stereotyped roles with a critical eye. The pinnacle of this denial is found in the Four Corners scene where , in his conversation with Charlie, he subtly acknowledges the stupidity of his dance but shrugs it off as a necessary step for his career. I think that Portland thus represents the assimilated indigenous- American who’s culture becomes significant only as a commodity that can be sold or used to further his career.

Hi Laen,

Awesome post here – thanks for this razor-sharp analysis (and for the shout-out here! haha). It seems like we covered pretty similar ground with our analyses here, and yet anchored on really interesting and crucial differences in working through King’s text. I love how much you’ve reframed King’s work as a functional middle finger to Fry’s monolithic means of evaluating artistry and Canadian national identity, and I think that Hovaugh as Fry absolutely checks out, and is perfect King mischief.

This is a little bit of a side-tangent, but one that’s been troubling me since I finished GGRW. You make mention of the Fort Marion setting here and ably tease out its sociopolitical relevance, which King alludes to a couple of times throughout the novel – enough so that I had been gearing up for it to serve as an inevitable site for the novel’s climax, where instead it felt like King bait-and-switched, drawing attention to its relevance, then abruptly changing gears. Why do you think King worked so actively to raise Fort Marion in the reader’s consciousness throughout the novel, without plunging more actively into engaging with it as a ‘breaking the fourth wall’ intrusion into the narrative, to the same extent that he does with the John Wayne Western here? I’ve been playing around with this ever since finishing the novel, and have yet to come to a satisfactory conclusion, so I’d love your two cents. Thanks so much for a great read, and comprehensive research!

Thanks for engaging with my blog, Kevin. Unlike many other university classes, this format really allows us to engage meaningful conversation around these topics. In a way, it echoes precisely what King seemed to be hoping to achieve in his novel. Rather than our academic thinking being a closed system, these dialogues uncover the many intersections between our varied perspectives and thematic fixations.

I love how you latched on the Fort Marion and it is an interesting question you pose regarding King’s choice to intrude upon the Western’s narrative but leaves the Florida “Asylum” relatively unscathed. It is an astute observation but , upon re-reading the ending, something that , I believe, King was very deliberate about. We are left with the image of the four escaped “Indians” returning to their cells and Joe Hovonaugh curling his toes in the plush carpet, staring our at his garden, musing about the changing seasons.

In the end, we are left , in many ways, back where we began. I believe that King, while purposefully disrupting traditional narratives, left the reader unsatisfied and frustrated with the lack of change. King gave us some satisfaction but ultimately leaves us hungry for deeper transformations.