Augustino Gabriele Ferrera and La Maison de la Ville

by Noah James

This is the story of Augustino Gabriele Ferrera, a prominent entrepreneur and Italian consul in Vancouver in the early years of the twentieth century, and the restaurant he managed, La Maison de la Ville. A.G. Ferrera was born in Italy in 1858, give or take a year, [1] and came to North America at age twelve, arriving first in New York and working at various jobs before eventually becoming a chef. [2] After working in California in the 1880s [3] he made his way to Canada. Moving to Vancouver in 1898 with his American wife, [4] he first managed The Savoy restaurant on Cordova Street [5], which was reported to be rivalled only by the Hotel Vancouver’s restaurant in quality. [6] In 1902 Ferrera embarked on a new venture, constructing a grander restaurant in a central location in the 400 block of Granville Street, which he named La Maison de la Ville. Ferrera’s aspirations for this new restaurant were even higher: he aimed to create the finest restaurant north of Portland. [7] To accomplish this, Ferrera had toured Europe and Eastern North America and “incorporat[ed] into his plan for an epicure’s palace in this city the notably good points of the best establishments in each of the centres of population”. [8] For the important role of head chef, he hired G. Genasso, formerly of the Hotel Del Monte in Monterey California. [9]

La Maison de la Ville, like The Savoy, primarily offered a French menu alongside some Italian dishes. There were likely a few reasons why Ferrera opened a French restaurant instead of an Italian one. Unlike today, at the beginning of the 20th century Italian food was not well known or well appreciated in North America outside of the Italian community, either as an everyday staple or in fine restaurants. A 1904 article in the Chilliwack Progress had to explain to uninitiated Canadians that Spaghetti should be eaten with a fork and a crust of bread, not cut into small pieces with a knife. [10] In keeping with the then established notion that French food was the pinnacle of cuisine, A.G. Ferrera had likely been taught his profession in French restaurants.

Almost immediately, La Maison de la Ville gained an enthusiastic clientele. Its 35-cent business lunches were popular with businessmen from Vancouver’s financial district, located just a few blocks to the east. Its advertised dinner special was just 50 cents, and included a seven-course French dinner accompanied by a small bottle of Californian wine. [11] Though these were undoubtedly good prices, they are better comprehended when compared to prevailing wages: In British Columbia in 1903 an unskilled, white male labourer made about 15 cents an hour. [12] Indigenous and Asian labourers, as well as white women, earned even less.

Figure 1: View of Vancouver’s West End from the tower of Holy Rosary Church, 1900. In the upper left are the Vancouver Opera House and The Hotel Vancouver. Courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives LP 103.1.1.

Located less than three blocks north of the Vancouver Opera House, La Maison de la Ville became the popular place for after-opera dining for Vancouver’s upper class. As early as July 1902 the restaurant was seemingly cemented as Vancouver’s best and most fashionable restaurant. A humorous article in the Vancouver Daily World describes a “dainty, chic young lady of the very West End” throwing herself down on the sofa and crying:

“Why, whatever is the matter,” her thoughtful mother asked- “wasn’t the opera any good-was it so sad-aren’t you feeling yourself? The opera was immense-yes, it was. But George-I’ll never speak to him again. You know what dainty little after-the-theatre suppers they serve at the Maison De La Ville? Well, the nasty, mean thing walked me right by the door and never once suggested that I’d like a bite. And me just dying for a sip of chocolate.” [13]

A.G. Ferrera was himself one of Vancouver’s elite residents, with a house in the West End at 970 Burrard Street [14]. In 1900 he had been named the first Italian Consul for Vancouver, overseeing the Italian community (then known as the “Italian Colony”) which in 1900 numbered about 200-300 people. [15] His restaurant was useful for functions related to his role as Italian Consul, including in 1905 hosting the officers of the Italian Cruiser Umbria, [16] which was in the midst of a round-the-world tour. [17] Unlike Ferrera, most Italians in Vancouver at the turn of the century were poor immigrants who had left Italy as the result of bad economic conditions. Most lived in the ethnically diverse east-end neighbourhood of Strathcona. [18]

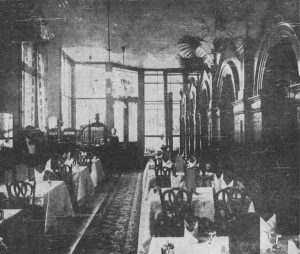

Figure 2: Interior of La Maison de la Ville, c. 1902. A.G. Ferrera is behind the Cashier’s Desk. The Vancouver Province, July 26 1947.

La Maison de la Ville would have a fairly short life. In 1904, after A.G. Ferrera had given over the daily management of the restaurant to a Mr. Fisher in order to focus on other ventures, the restaurant became the centre of a story that briefly scandalized the city. It was revealed that Mr. Fisher had been serving alcohol to underage girls, including a 15-year-old, in an effort to encourage their male companions to “blow their money” on the restaurant (the scheme had worked: in court it was discovered that an astounding $8.50 was spent on a dinner for four people). [19] After an inquiry, Fisher was given the maximum fine of $50, and the restaurant’s licence was revoked. A.G. Ferrera quickly retook control of the restaurant. [20]

Although there were no accusations, in the newspapers at least, that he knew about what had been going on or was responsible, his restaurant seemed to be targeted by Vancouver’s authorities from then on. In April 1904 his reapplication for a restaurant licence (necessary to serve alcohol) was rejected when the motion to grant the licence failed to find a second. [21] Unnoted in newspapers or official documentation may be the influence of the wives of city officials: In 1904 the Temperance Movement was gaining steam in Vancouver, led by Protestant women in organizations such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. It is likely none of the commissioners wanted to have to tell their wives that they were responsible for returning a licence to the restaurant that had so recently been involved in scandal.

At some point in 1904 Ferrera did manage to reacquire a licence, but the next year the restaurant was again targeted. In July 1905, after the board had allowed Ferrera to renew his licence, the city suddenly raised the licence cost from $100 to $1000, retroactively applying the increase to La Maison de la Ville. Ferrera’s lawyer believed the price raise to be “not only prohibitive but also discriminatory”. [22] In August Vancouver’s health department attempted to shut the restaurant down with questionable accusations of poor hygienic conditions in the alley behind the restaurant. These charges were reluctantly withdrawn by the police when Ferrera agreed to comply with all requirements, [23] but it seems the licencing costs were too prohibitive, and the restaurant quietly closed soon afterwards.

In 1906 A.G. Ferrera went on a holiday, travelling extensively throughout Italy. [24] After returning to Vancouver he put his energies into other entrepreneurial pursuits, including the building of Ferrera Court [25], a large apartment building that still stands at the corner of Jackson and Hastings Street, as well as briefly serving as the manager of the Castle Hotel restaurant. In 1913 he was given the title of “Cavaliere” (the equivalent of a knighthood) by the Italian King for his long service as Italian Consul. [26] In 1914 he resigned from his position as Consul and moved to Chilliwack, where he spent his later years building up a factory producing “Ferrera Cream Cheese” which eventually produced 6000 pounds of cheese a month [27]. He died in 1948 at the age of 90. [28]

Figure 3: The former Maison de la Ville c. 1909 when it was the home of C.D. Rand Real Estate. Courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives Bu P526.1.

References

[1] “Augustino Ferrera,” The Chilliwack Progress, September 9, 1948.

[2] “Cleared Stumps from site of Vancouver Cafe”, The Province, July 26, 1947.

[3] “AG Ferrera, meals for jury,” The Fresno Weekly Republican, October 18, 1889.

[4] 1901 Canadian Census, British Columbia, Burrard District, 5.

[5] “Cleared Stumps from site of Vancouver Cafe”, The Province, July 26, 1947.

[6] Major J.S. Matthews, Early Vancouver Volume Two, (Native Pioneers of Vancouver, 1933), 342.

[7] “Brick Block opposite the Postoffice,” The Province, Oct 12, 1901.

[8] “Vancouver’s Restaurant Palace to be Opened this afternoon,” Vancouver Daily World, February 8, 1902.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “What to Eat With the Fingers,” Chilliwack Progress, April 27, 1904.

[11] Cleared Stumps from site of Vancouver Cafe”, The Province, July 26, 1947.

[12] Mary Mackinnon, “New Evidence on Canadian Wage Rates, 1900-1930,” The Canadian Journal of Economics Vol. 29, No. 1 (February 1996): 119.

[13] “Where the Opera was Spoiled,” Vancouver Daily World, July 22, 1902.

[14] Henderson’s City of Vancouver Directory 1907, (Vancouver: Henderson Publishing Company, 1907), 126.

[15] “Vancouver’s Sympathy,” The Province, August 1, 1900.

[16] The Province, June 9 1905.

[17] “Hurrah for the Red, White and Green,” Vancouver Daily World, June 8, 1905.

[18] John Atkin, “A Brief History of Little Italy,” accessed February 16, 2022, https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/brief-history-of-little-italy.pdf.

[19] “Highest Fine is imposed against Fisher,” Vancouver Province, March 15, 1904.

[20] “Mr. A.G. Ferrera to resume management of the Maison de la Ville,” The Province, Mar 21, 1904.

[21] The Province, April 13, 1904.

[22] “Will not Enter Suit,” The Province, August 4, 1905.

[23] The Province, August 10, 1905.

[24] “Canadian Exhibits made hit at Milan,” The Province, Oct 13, 1906.

[25] “$100,000 Apartment for Hastings East,” The Daily News Advertiser, December 22, 1912.

[26] “Italian Consul is honored by King,” Vancouver Daily World, Friday Feb. 7, 1913.

[27] “Making 6000 pounds of Full Cream Cheese here each month,” The Chilliwack Progress, June 30, 1927.

[28] “Augustino Ferrera,” The Chilliwack Progress, September 9, 1948.

Bibliography

Atkin, John. “A Brief History of Little Italy.” accessed February 16, 2022.

Henderson’s City of Vancouver Directory 1907. Vancouver: Henderson Publishing Company, 1907.

Mackinnon, Mary. “New Evidence on Canadian Wage Rates, 1900-1930.” The Canadian Journal of Economics Vol. 29, No. 1 (February 1996): 114-131.

Matthews, Major J.S. Early Vancouver Volume Two. Native Pioneers of Vancouver, 1933.

Newspapers.com. “Newspapers.com.” Accessed February 16, 2022.

Zanoni, Elizabeth. Migrant Marketplaces: Food and Italians in North and South America. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

1901 Canadian Census, British Columbia, Burrard District.