Convergence, Capitalism, and Crime: Keeping Kosher in the Kitchen for the New, New York Jew

by Helena Minsky

From 1881 to 1914, 2 million Jewish immigrants moved to the United States from Easten Europe. [1] With this influx came new recipes, and also new needs. Jewish food, often subject to the kosher rules of the religion, is by nature a varied and migratory tradition, fuelled by the diasporic groups which make up the community. How to obtain products that were kosher to maintain religious traditions was added to the list of responsibilities for any Jewish cook, but in entering into the unmitigated capitalism of the New York markets, kosher was complicated. By looking at the production and consumption of kosher food in New York, through newspapers, a cookbook, and historical articles, the nuances of Jewish food and culture post-migration are highlighted, as well as the impact of crime on the kosher market and its consumers.

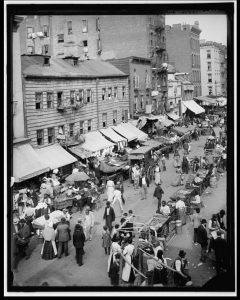

Jewish market on the East Side, New York, N.Y. United States, New York, New York State. [Between 1890 and 1901].

Published by Detroit Publishing Co.

Florence Kreisler Greenbaum’s The International Jewish Cook Book: A Modern “Kosher” Cook Book, published in New York, 1918, is an exemplary artifact of the combined cultures within Jewish cooking. Even the book’s subtitle indicates its international aspect, detailing “the favorite recipes of America, Austria, Germany, Russia, France, Poland, Roumania, Etc., Etc.” [2] The gendered aspect of cooking is also highlighted in Greenbaum’s cookbook, which has parallels in New-York Italian migrant culture of the early 20th century, which also saw food preparation as a largely feminized consumerist output. [3] Greenbaum notes that the book is directed to “ensure success to the inexperienced housewife … without transgressing the dietary laws.” [4] With this direction, Greenbaum’s book serves a dual role, as both to uphold and promote the social role and culinary pursuits of women, and also to maintain the religious participation of these women and their families. In addition, the collection of the recipes from multiple cultures, centered around a religious identity, indicates the cultural importance beyond national identity, which was rooted and expressed in the culinary decisions of the Jewish migrants making their home in New York and other American cities.

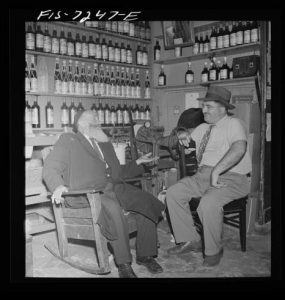

With the kosher tradition linking the Jewish diaspora, the question of where to buy kosher products, and at what price, was of high importance. For a food to be kosher, it must adhere to strict dietary laws throughout its production and distribution, with meats and wine requiring certification from a rabbi during preparation.

New York, New York. Rabbi in the Jewish section passing the time of day with the proprietor of a kosher wine shop where sacrificial wines are sold. United States, New York, New York State, 1942. Photographed by Marjory Collins.

In New York, as Jewish people left their Eastern European homes and synagogues, there was difficulty in finding affordable meats that had been prepared according to kosher law. In Eastern Europe, as explained by Aaron Welt, “governing Jewish authorities of the state-sanctioned kahal, Hebrew for “community,” contracted with kosher slaughterers, or shochetim, in a tightly regulated system of kosher meat purveyance” however, in New York, the same system could not be continued, as the US state would not intervene on religious issues. [5] Because of this, kosher food in America was increasingly unsanctioned, and it was seen by international Jewish communities as an “unkosher land.” [6] Additionally, prices were often too high for the consumers, who were largely immigrant women, leading to an eventual consumer strike in 1902, which proved successful. [7] These kosher riots demonstrate the strength of immigrant Jewish women as consumers within their communities, but also highlighted the problem with the New York kosher markets and their unmitigated nature. The 1902 strike was also not the last, and a similar one was seen 1910, as women poured kerosene over kosher meat and raided shops, again in protest of the rising prices. [8]

It is also important to note that while consumers were Jewish women, the production side of kosher meat was tied heavily to Jewish crime bosses and gang members, who regulated and controlled the industry, and were also used to dispel rioters. [9] The violence within the kosher industry is exemplified in the case of Barnett Baff, a Polish immigrant who had control over a large portion of the kosher poultry industry in New York. Baff worked against the Greater New York Live Poultry Dealers Protective Association (NYLPDPA), a consolidation of various poultry producers, by creating conflict between workers and the NYLPDPA, with the help of hired gangs. [10] Baff also attacked NYLPDPA producers legally, successfully accusing members of restraining commerce. [11] With the power he gained from these actions, Baff would artificially increase or decrease prices at will, in order to benefit his enterprise. [12] In November, 1914, Barnett Baff was assassinated by competitors, demonstrating the harsh realities and violence in the production of kosher goods, and the organized crime that controlled them. [13] On November 25th, the day after the assasination, the killing was reported in the New York Times, who noted that,

“it was charged that [Baff] controlled the retail poultry trade and was accustomed to fix the wholesale price and then under-sell retail dealers who had bought from him especially at times of Jewish holidays, when unusual quantities of poultry were sold on the east side.” [14]

While Baff was dead, the strong armed tactics that he had used continued, and gangs and strong men played a large role not only in kosher poultry, but other kosher industries as well, including bakeries. [15]

The crime of the kosher food producers may not have been entirely visible to the average Jewish consumer, but as they went to the market, the prices that were risen due to the likes of Bernard Baff and his contemporaries affected their dietary decisions. In Greenbaum’s cookbook, eggs are offered as a substitution for meat, as “even when high in price; [eggs] make a cheaper dish than meat.” [16] The publishers of the book also note that “Mrs. Greenbaum knows the housewife’s problems through years of personal experience, and knows also how to economize,” [17] pointing to an understanding and acknowledgement of the limited capital available to the cookbooks users. As women struggled to feed their families, taking in boarders, participating in informal labor such as the pushcart trade, and working for local businesses, purchasing food at a good price was integral to survival, and immigrant Jewish women showed time and time again that they were willing to stand up for themselves and their families against the kosher price hikes, especially during times of economic depression in the beginning of the twentieth century. [18]

References

[1] Kathie Friedman-Kasaba, Memories of Migration: Gender, Ethnicity, and Work in the Lives of Jewish and Italian Women in New York, 1870-1924, (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 2.

[2] Florence Kreisler Greenbaum, The international Jewish cook book: a modern “kosher” cook book (New York: Bloch publishing company, 1918), title.

[3] Elizabeth Zanoni, Migrant, Marketplaces: Food and Italians in North and South America (Urbana, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2018): 105.

[4] Florence Kreisler Greenbaum, The international Jewish cook book: a modern “kosher” cook book (New York: Bloch publishing company, 1918), 11.

[5] Aaron Welt, “Butchers, Bakers, and Jewish Strong-Arm Men: Organized Crime in the Kosher Food Trades During the Age of Mass Jewish Migration, 1900–1917,” Journal of American Ethnic History 40, no. 2 (Winter 2021): 95.

[6] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,” 96.

[7] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,”96.

[8] “Riot Over Kosher Meat: Women Seize Purchases and Pour Kerosene Over them,” New York Times (1857-1922), May 10, 1910,

[9] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,” 96.

[10]Aaron Welt, “Butchers, Bakers, and Jewish Strong-Arm Men: Organized Crime in the Kosher Food Trades During the Age of Mass Jewish Migration, 1900–1917,” Journal of American Ethnic History 40, no. 2 (Winter 2021): 98-101.

[11] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,” 98-101.

[12] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,” 98-101.

[13] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,” 92.

[14] “Murder Merchent and Escape in Auto: Bernard Baff, Poultry Trust Rivel, shot Through the Heart in Street. Lured by Telephone Call Crowds Miss Car Number;- No Clue to Murderers ;- Victime Often Threatened,” New York Times (1857-1922), Nov 25, 1914,

[15] Welt, “Butchers, Bakers,” 114.

[16] Florence Kreisler Greenbaum, The international Jewish cook book: a modern “kosher” cook book (New York: Bloch publishing company, 1918), 193.

[17]Florence Kreisler Greenbaum, The international Jewish cook book: a modern “kosher” cook book (New York: Bloch publishing company, 1918), iii.

[18] Kathie Friedman-Kasaba, Memories of Migration: Gender, Ethnicity, and Work in the Lives of Jewish and Italian Women in New York, 1870-1924, (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 127-129.