This semester I enrolled in “ENGL 419: History of the Book,” a course designed especially to encourage students to interact with archival materials. Half of the time – more, even – classes took place outside “the classroom” in UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC).1 My eyes were opened to the amount of stuff in UBC’s libraries that wasn’t on the shelves – in some cases, stuff that wasn’t even in book-form. As an English student, it was humbling to recognize that in my studies I had been prioritizing a certain kind of reading material that had shaped my thoughts around what counted as “reading.” But I engage in various reading materials on a daily basis, most of the items I “read” aren’t even books, sometimes aren’t even traditionally textual, let alone literary. Michael Twyman gives a good reminder that we interact with a variety of printed materials that we “read” in different ways:

When we consider print … there is a good chance that books spring to mind. We have to remind ourselves therefore that printing has never been limited to books … [and] include[es] newspapers, magazines, maps, sheet music, playing cards, religious prints, bookplates, notices, posters, security printing, forms, invitations, packaging, and even more ephemeral items than these.2

D.F. McKenzie adds that even non-print materials, such as films, can be “read” and can be labelled “texts” because “their function is still to create meanings by the skilled use of material forms.”3 Authors, publishers, readers, and literary critics do not have a monopoly on the use of the word (or concept) of “text”:

Filmmakers, spectators, and critics all think in terms of films as texts, because some such word makes sense of the discrete parts of which a film is constructed. The concept of a text creates a context for meaning. In other words, we are back to the initial definition of text as a web [The word “text” comes from the Latin textere, to weave, also the root of “textiles”], … and discover that, however we might wish to confine the word to books and manuscripts, those working in films find it indispensable.4

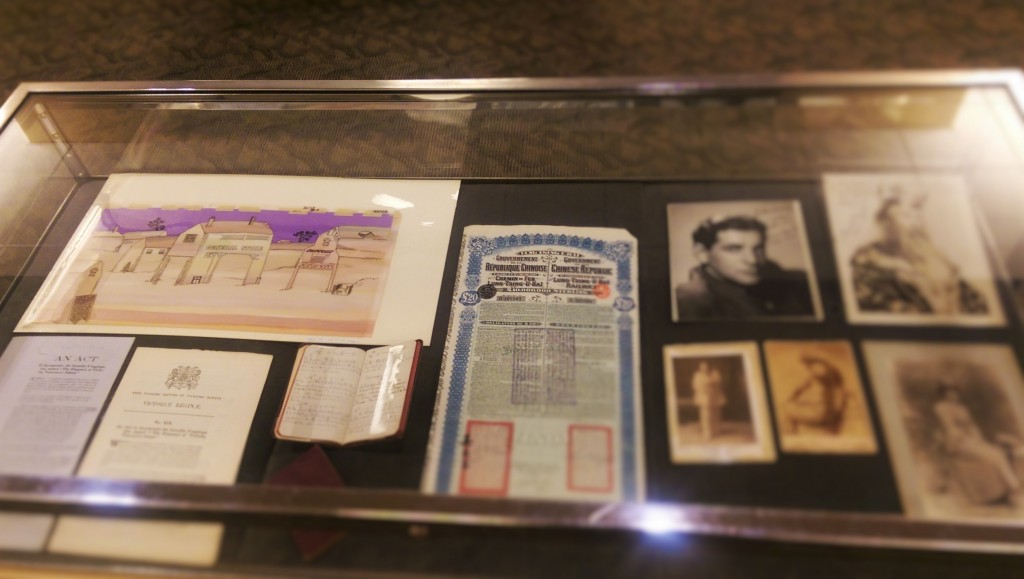

During one of our days in RBSC, my attention was drawn to a flash of purple in one of the display cases:5

Here was an artifact that was neither book nor film, but nonetheless a material object: an animation cel. One piece (or piece of “text” in McKenzie’s use of the word) in the composition of an animated film. I endeavoured to find out more about it and about who had made it – to find out how it was made, what it was used for, and how it made its way to UBC. Read more of my blog to find out what I discovered.

- Located in the basement of Irving K. Barber Learning Centre. http://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/.

- p. 44: Twyman, Michael. “What is Printing?” The Broadview Reader in Book History. Ed. Michelle Levy and Tom Mole. Toronto: Broadview Press, 2015. 37-44. Excerpt from The British Library Guide to Printing. London: British Library, 1998. 8-17. Print.

- p. 55: McKenzie, D.F. “The Dialectics of Bibliography Now” The Broadview Reader in Book History. Ed. Michelle Levy and Tom Mole. Toronto: Broadview Press, 2015. 45-61. Excerpt from Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts. London: British Library, 1986. 55-76. Print.

- p. 54: Ibid.

- Sens, Al. Farmland background [animation celluloids]. [19–?]. Al Sens Collection. RBSC-ARC 1729, box 2, folder 34. Rare Books and Special Collections, Irving K. Barber Learning Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.