On a cold February night in 2004, a watchman on shift at the Squamish Terminals peers into the water and sees milt, a byproduct of herring fertilization. This may not intuitively seem like a grand proclamation, but in a region where herring had not been seen for years, it was a big deal indeed. However, when others arrived in the daylight to investigate his claims, they saw nothing. For two years this went on until, eventually, a man by the name of Jonn Matsen ventured under the docks and, shockingly, discovered hundreds of millions of herring eggs laid upon the dock pilings. The kicker? They were all dead.

* * *

Under the docks of an industrial shipping terminal may not be where you expect a fish stock recovery story to take place – it is certainly worlds away from the idealistic marine protected area scenario that many associate with conservation. Nonetheless, a group of dedicated citizens who make up for what they lack in formal conservation training with strong adaptive management skills, passion, and creativity, have managed to pull a success story out of these shadowy waters. Jonn Matsen, the man who discovered the dead roe, co-chairs the Streamkeepers Society with Jack Cooley. The Streamkeepers are a local volunteer based initiative that strives to “Maintain and enhance riparian habitat of [their] local streams so that fish, especially salmon… can navigate streams and successfully spawn; and to enhance then maintain herring spawning habitat in the upper Howe Sound”.

Howe Sound, the inlet where the town of Squamish is located, was once abundant with Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii), but after years of industrial development of the inshore waters destroying the algal beds and eelgrass(1) where they spawn the population seemed to have all but vanished. The disappearance of this subpopulation was so dramatic that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada ceased to monitor Howe Sound herring in the 1970s.

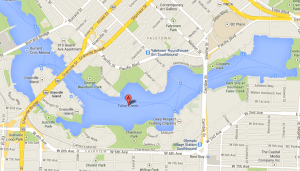

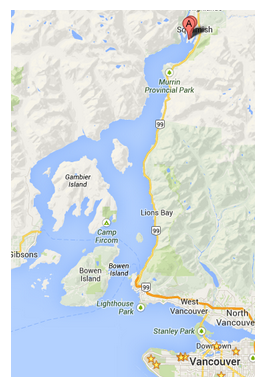

The project took place underneath the terminals in Squamish, located at the tip of the Howe Sound inlet. (Source: Google Maps)

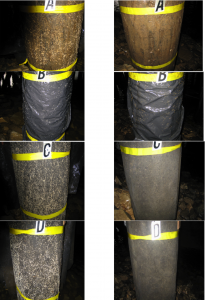

February 2007 March 2007

The herring roe were found to die and turn yellow on the control (A), fail to stick to the plastic surface alone (B), stick but die from leached creosote through the weed control alone (C ), and both stick and survive (D). (Source: Jonn Matsen)

The dock pilings of the Squamish Terminals, like most wooden structures in water, had been treated with a wood preservative, specifically creosote. This preservative is a mixture of over 300 compounds, some of which are known to be toxic to organisms. The effect of creosote on herring roe has been studied and shown to reduce the hatch rate by 90%, with those that do manage to survive often suffering severe deformities such as scoliosis (2). Putting two and two together, the Streamkeepers realized that it was the creosote in the pilings that was killing the roe and leapt to action. They decided to try wrapping the pilings in various materials to see if they would reduce the exposure to the toxic chemicals. Trials were then set up to compare the effectiveness of plastic, weed control material, and plastic under weed control material, as compared to the unwrapped control pilings. The wood wrapped in weed control over plastic came out on top, presumably because the plastic reduced the amount of creosote the roe were exposed to, and the weed control was the proper texture for attachment.

In Spring 2006, thanks to tremendous volunteer efforts, the first 60 pilings were wrapped, and there appeared to be an increase in the hatching success of the roe. Later, 171 more pilings at the Squamish Terminals were wrapped and a 260m by 2m float line was added as well to provide an even greater surface area for successful spawning. All in all, the volunteers of Streamkeepers have wrapped over 200 of the 600 creosote pilings at the Squamish Terminals(3), providing massive surface area for Pacific herring to lay their roe for both the February and March spawning events. In an unlikely alliance between industry and conservation, the Squamish Terminals themselves have played an active role in the Streamkeepers initiative to rebound the herring population. The Terminals have granted the Streamkeepers access to the docks, aided in the cleaning and storage of the float line, provided funding for wrapping materials, and help raise awareness of the project by featuring it in their bi-annual community newsletter. Both parties agree that the relationship between them has been a very postitive one, and that they hope to keep working together in the future.

Due to the above-mentioned lack of monitoring of this herring population, standard measures of success for population recovery are non existent. However, that does not mean that the success of this project cannot be seen reflected in Howe Sound and the Squamish community. Success for the project can be looked at in many different ways: an increase in the hatch out rate of herring roe on the wrapped pilings, increase in the sightings of herring roe in Howe Sound, potential changes in the biodiversity of the region, and community awareness of the project as well as expansion to other communities.

Survival of the roe can be determined visually; when the roe die they turn yellow. By wrapping the pilings the majority of eggs survived as indicated by the color difference. This increase in roe survival has been credited with boosting the herring population of the area. Being an essential food source for many predators, it is thought by many that the surge in herring has revived the entire foodweb. Many citizens believe that the abundance of herring is bringing species into Howe Sound such as dolphins and humpback whales that haven’t been seen in the area for many years. Elk and seal pups have also been seen at the waters edge feeding on the roe, much to the delight of the local Squamish community. Whether there is a real connection between the increased herring and increased sightings of marine mammals is difficult to say. Dr. Andrew Trites, marine mammal expert at the University of British Columbia is cautious in assigning a link between the two since there are too many variables when it comes to the ocean. He illustrates with an example: Pacific white-sided dolphins are routinely spotted in new locations due to their recent introduction to the region, so their increased sightings in Howe Sound are nothing out of the ordinary. Regardless of it’s cause, it’s clear that the local citizens are enamored with the increased biodiversity in the area.

There has been an increase in awareness about the herring population itself within Squamish. There have been numerous glowing newspaper articles and newsletters about the project. The work by the Streamkeepers has brought to light an issue that many in Squamish and the surrounding area may not have been aware of. There seems to be a renewed sense of appreciation and ownership for the Pacific herring. One long time community member and steward of the local bald eagle population has put forward the idea of a community Herring Festival to celebrate the return of herring in Howe Sound. Conversations with citizens of the Squamish community all lead to a similar conclusion – the Streamkeepers project is a success. Randall Lewis, Environmental Advisor of the Squamish Nation and President of the Squamish Watershed Society, feels that wrapping the pilings made a significant difference in preventing herring mortalities. Doug Hackett, Vice President of Information Services and Administration at the Squamish Terminals expressed that the Streamkeepers were successful in taking a large issue and applying a simple solution. It’s not feasible for the Terminals to remove the pilings currently in use, but this project provided a reasonable solution to mitigate the detrimental effects of creosote on the herring roe.

This local initiative provides an excellent framework that other communities can adopt, which is what’s happening in the False Creek community of Vancouver. False Creek is a short inlet adjacent to downtown Vancouver. It’s thought that it was once very productive spawning grounds for herring, but similar to the situation in Squamish, development over the years has reduced the natural spawning area which has been replaced with creosote treated docks and marinas. The Squamish Streamkeepers are currently working with the False Creek community to promote herring survival. They plan to wrap about 20 pilings at Fisherman’s Wharf, near Granville Island. Test wrapping of a few pilings this past winter showed herring had spawned on the materials, so the group is confident they can aid the herring in False Creek the same way they have in Howe Sound.

While a long-term ambition for BC might be to follow the lead of Washington in banning all creosote in coastal development and removing existing structures, the cost of such an endeavor makes it still far off in the future, highlighting the need for ‘damage control’ in the meantime. The Streamkeepers provide an excellent example of how a community group can rise to the occasion and affect change with creativity, passion, and efficiency.

To stay up to date on the activity of the Squamish Streamkeepers, like them on Facebook!

Posted by: Emma Jackson, Shari Mang, Kalie Mcgratten

Question? Comments? Queries? Tweet us!

@emma_mjackson

@sharilynn_m

@kaliejoelle