Scenario 1.

Data overdrive: How much data is too much data?

Subject: what do you think about the new harvest helmets?

Friends,

I know a lot of us just accept that school is the way it is, but have you ever thought of all the ways we’re being watched? Like really thought about it?

My mum says smart watches and eye tracking were around even before her time; ancient holdover technology from the early part of this century. I suppose schools make us use them because they’re so cheap and because so much of the current school budget has been used to purchase Harvest Helmets from Datum Fortis. The way I understand it, our smart watches are synced with the schools Central Data Gathering Authority (CDGA) and send information about our sleep cycles, activity levels, heart rate, and body temperature. There are rumours too, that the watches also send information about how often we go to the bathroom and when we’re on our periods, but I can’t say for sure because the data collection has never really been explained to us other than the school motto “gather, manage, monitor.” As for eye tracking, all of our devices are equipped with software that simultaneously tracks what apps, websites, and virtual worlds we participate in, as well as how long we interact with these spaces and where our attention is spent. If we choose to write by hand, our digital pens send data to the CDGA, including how often we pick up our pens and put them down, how long we spend writing, and how often we erase or cross out our work. It also analyzes our pen grip as a metric for stress, similarly, our digital paper is pressure sensitive for this same reason, did you even know that? I haven’t even touched on the fact that anything we produce as students is collected, coded, sorted, aggregated, and analyzed, but this is such a common practice that I don’t think students even acknowledge it’s happening. The latest technology to come out of Datum Fortis, the for-profit leader in ed tech, is the harvest helmet, since (apparently) our smart watches, pens, and computer monitoring software are not enough. The Datum Fortis harvest helmets collect our brain activity using proprietary cerebrum interference technology and we’re expected to wear them at minimum for the hours we’re engaged in school activity, but we’re strongly encouraged to wear them for as long as we can tolerate having them on. I think the CDGA, ideally, wants to be able to data-mine our brain activity on non-school activities as well. The thing is, no one tells us anything about how all this data collection and mining works and to what end. I’m not even certain that this technology is one way, how do I know if the helmet is feeding me information or altering my brain in some way? How can I be certain where my data is going? How long is the data stored for? If you also want these questions answered, sign the petition for the “freedom of discovery” request I’ve attached to this email.

Unity and mutiny,

Daphne

P.S. Did you know that Datum Fortis is a subsidiary of the media conglomerate DisNet?

Scenario 2.

Living tissue masks: a breath of fresh air

The Covid-19 pandemic has certainly brought to the forefront of people’s mind the realities of communicable diseases and the vectors that spread them. As the climate continues to change and warm, we can expect the incidences of known (and possibly unknown) communicable disease to rise. Simultaneously, climate change can also negatively impact local air quality.

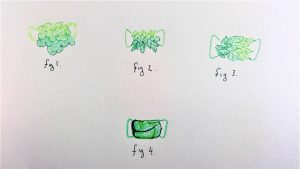

As people become accustomed to wearing masks it makes sense to leverage this new norm to tackle the dual problems of airborne disease and poor air quality. At Studio Plante we have conceptualized and prototyped the living tissue mask. Taking inspiration from nature, the idea for the living tissue mask capitalizes on the abilities of plants to purify surrounding air. Research has shown that plants like Epiprenum aurum, aka pothos ivy, use enzymes to remove toxic chemicals from the air, and scientists have already been able to boost this ability by splicing in the animal 2E1 gene, which expresses enzymatic activity. One challenge to developing the living tissue mask is keeping it alive, and pothos has a root system that requires submersion in water or soil. To overcome this challenge, the already genetically modified pothos plant, can be spliced further with genes from the genus of plants known as tillandsia, or more commonly, air plants. Pothandsia, as we have come to call it, retains the air purifying ability of the transgenic pothos, combined with tillandsia’s ability to live in low moisture conditions on a variety of substrates (including both living and non-living substrates).

Our living tissue mask is made out of pothandsia grown on an organic muslin substrate and survives off the natural circulation of air from breathing, as well as the moisture content in the wearer’s breath.

Users of the mask will find improved breathability, enhanced air quality, and a significant reduction in disease exposure. Our belief at Studio Plante is that health and climate are a community responsibility, and it is for this reason that we have made our research and design open access.

Living Tissue mask prototypes

Reflection

When creating the speculative future scenarios, I considered a few ideas from Dunne and Raby’s (2013) book Speculative Everything:

- Don’t try to predict the future, instead create ideas that lead to discussion around the kinds of futures people really want

- Start with a what if question

- Keep scenarios scientifically possible

- Provide a clear path from where we are presently to the speculated future scenario

- Represent ideology and values

- Choose a purpose (critique, entertainment, catalyst for change, inspiration, reflection)

In Scenario 1, I wondered: what if data-driven education is taken to the extreme? This is not a prediction of where education is going, but a scenario that offers critique and reflection on what that world might look like. I imagined more of a dystopian future and hopefully the scenario brings to mind ideas around the ethics of data collection, such as surveillance, algorithms, and transparency. Additionally, perhaps it sparks questions such as, how much data is enough data? And who gets to access the data? Maybe it brings to mind ideas of data storage, what do we keep, what can we afford to lose (Brown University, 2017)?

For scenario 2, I was moved by the idea in Speculative Everything (Dunne and Raby, 2013) of imagining how nature could be different. This scenario, rather than a ‘what if,’ takes the shape of a thought experiment. I considered a more idealistic speculative future where design isn’t driven by market forces, but one that represents values such as care for humanity. While thinking of this scenario, I was reminded of technology such as parchment which capitalized on animal tissue to create writing substrates that were durable and long lasting. Additionally, I tried to create a clear path for how we can take our current scientific understanding of genetically modified organisms to create a mask that could possibly be made out of living tissue. For example, pothos has been genetically modified with a gene for an enzyme from rabbit liver (Zhang et al., 2019) and it is true that air plants can survive on many types of substrates in relatively low moisture conditions (Tillandsia, 2021). As for whether or not pothos could be further genetically modified with genes from air plants, that has yet to happen, but seems plausible.

One thing that I didn’t mention in my scenario, but did think about with respect to education, is that indoor air quality is often poorer than outdoor air quality, and if students are required to wear masks in school, why not use masks that purify the air?

References

Brown University (2017, July 11). Abbey Smith Rumsey: Digital memory: What can we afford to lose [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBrahqg9ZMc.

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Tillandsia (2021, March 4). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tillandsia&oldid=1010258005

Zhang, L., Routsong, R., & Strand, S. E. (2019). Greatly enhanced removal of volatile organic carcinogens by a genetically modified houseplant, pothos ivy (epipremnum aureum) expressing the mammalian cytochrome P450 2e1 gene. Environmental Science & Technology, 53(1), 325-331. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b04811