This task is a redesign of the original “what’s in your bag task” and when I think about the purpose of the original task I think about it from the perspective of identity texts. What do the things we carry say about who we are and our identity? I had discussed the concept of “mom pockets,” the game I play with friends about the things we carry in our pockets that are specific to our roles as parents. I have realized that much of my identity is in relationship to others and this cannot be fully conveyed through a written discussion of items. Dobson and Willinsky (2009) make the point that writing is formal and monologic, whereas speech is informal, interpersonal, and dialogic. Likewise, The New London Group (1996), draws our attention to the idea that different modes of communication draw forth different languages. I decided for this redesign that I would play with my understanding of modes of communication, identity, and texts by a) using social media for “mom pockets” to summon a check on my common identity with other moms and b) by recording a conversation with one of my closest friends about “mom pockets,” and identity. To me, it’s a much richer discussion to talk about the things we carry as relational items and as texts situated in a shared identity. The interesting story that the ‘texts’ that I carry tell is what The New London Group (1996) might describe as the representation of a shared cultural context.

When you listen to the recorded audio conversation of my friend and myself, not only do you hear us speak to a shared common identity, but you literally hear our shared common identity in our conversation pattern, our conventions of speech, and the language we use to make meaning. A theme that has come up in multiple readings (Dobson and Willinsky (2009); Kress 2004) is the loss of immediacy in written work. The audio recording instead affords an immediacy that my original written assignment lacks, and we can hear the give and take of a shared common identity. If we consider the claim that Dobson and Willinsky (2009) make about writing (formal, monologic) vs. speech (informal, dialogic), we can see how they framed them in opposition. In this sense my first version of the task and this version of the task may be considered opposite modalities. I’ve also included a social media component which can be framed as a cross modality of both written and speech, in that it is written, but aims to mimic the informal nature of face-to-face communication.

This audio clip represents the first half my discussion with my friend about “mom pockets.” The discussion includes the items in our pockets, our identities as parents, whether or not dad pockets exist, and a little discourse on the way woman, specifically, are socialized to parent. I’ve excluded the second half of our discussion as we digress into pandemic parenting.

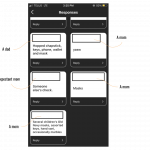

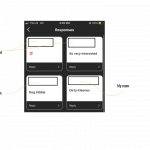

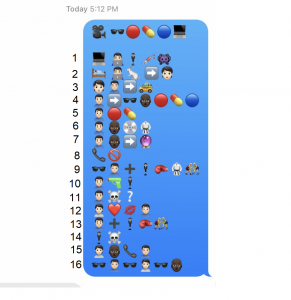

Below is an image gallery of screenshots of how I use social media and “mom pockets” to summon a common identity

- Instagram “questions” feature

- Annotated responses. User handles have been omitted

- Annotated repsonses

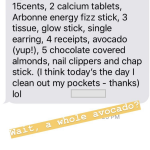

(Future Deirdre here: I saw that I could pull up very old stories in Instagram through the highlights option, so I’m able to include past, pre-pandemic “mom pockets,” including the infamous avocado pocket mentioned in my audio recording.)

- A single sock

- kinder egg toys

- Avocado pocket

References

Dobson, T., & Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. In D. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 286-312). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and Learning. Computers and Composition 22(1), 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review 66(1), 60-92.