First year of University has been filled with realizations and moments of introspection that I haven’t experienced at any point in my life prior. A particular moment that resonated strongly with me was when we really immersed ourselves into the genre of trauma. Not exactly a moment per se but definitely a topic. It hit me strongest when we read Jonathan Safran Foer’s novel Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

The aspect of trauma that I had not explored extensively was comprehending it as something beyond a phase. I heard trauma and I thought of it loosely as a step by step program. You experience some event that has a painful effect on you, you struggle to deal with it, then you move on. It exists as a traumatic experience from then onwards, it remains simply as something that happened. What I had not entirely explored was how people rarely leave their traumas behind. Sometimes pain by trauma isn’t something that happened, it can be something that is happening.

I say this, but at the same time I still think that I understood trauma to be something that sticks around for people. I think, however, that I saw the traumatic aspects of people as their “sad side”. In a sense, I guess I only saw trauma as infiltrating the sad and depressed areas of peoples lives. The realization that I came to more fully, however, was that trauma doesn’t exist only in your dark corners, it can become the dominating force in all areas of your life and personality.

The way that the grandfather in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close loses control over his trauma and has it take over him is when I understood the power that an undying trauma can have. In every sense both physically and emotionally the trauma became this man. He couldn’t speak for it brought him too close to his experience of trauma, he couldn’t even confront his trauma so he created areas that existed as nothingness where he merely existed to exist.

This trauma understanding instilled in me a realization towards the process of trauma. I realized, getting past a trauma isn’t about swimming through a choppy canal and it’s not about trying really hard to not be sad anymore. Getting past a trauma is about accepting that the trauma is a part of you but that it doesn’t need to consume you. Getting through trauma isn’t automatic, it doesn’t come just by having time pass by, it comes by confrontation. Trauma is intimidating and unforgiving, it doesn’t care about you at all as long as it consumes you. Trauma won’t stop until you can’t separate the trauma from yourself.

I want to end my final blog with a few questions of introspection, are you aware of a trauma that is having an effect on you? Are you aware of how much of an effect it has on you? Is that effect negative or positive? The most salient point that I want to draw from this is that addressing trauma and pain is important and necessary, without it you will get lost and your trauma will do more harm then you could anticipate.

Hope you enjoyed my blogs,

Isaiah

Foer, Jonathan Safran. Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close. Boston, MA: Mariner, 2005. Print.

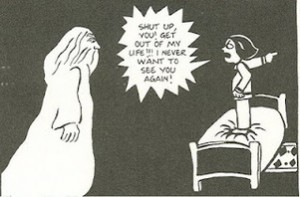

. 70 Satrapi exclaims at God: “Shut up, you! Get out of my life!!! I never want to see you again!”. There is a redefinition of religion for Satrapi. She succeeds in showing the spectrum of emotion and frustration towards religion in an entirely childish way, but at the same time also in a very advanced way. The dialogue and emotions are ones that people of all ages can relate to, but the critique and questioning of God is something that most people do not do until they are much older.

. 70 Satrapi exclaims at God: “Shut up, you! Get out of my life!!! I never want to see you again!”. There is a redefinition of religion for Satrapi. She succeeds in showing the spectrum of emotion and frustration towards religion in an entirely childish way, but at the same time also in a very advanced way. The dialogue and emotions are ones that people of all ages can relate to, but the critique and questioning of God is something that most people do not do until they are much older.