In recent years, inequalities have come to light potentially more so than ever before including racial divides, and the distribution of wealth. More specifically, in the United States, the middle class, the once substantial majority of Americans, has shrunk considerably. With this, the wealth gap between upper-income families and middle- and lower-income families is growing more rapidly. According to a study by Pew Research Centre, “upper-income families had 7.4 times as much wealth as middle-income families and 75 times as much wealth as lower-income families” in 2016 (Horowitz et al., 2020). Additionally, racial wealth divides have also grown. In the US, median black household income was 61% of median white household income in 2018, which is slightly up since 1970 (Schaeffer, 2020). Beyond just the racial, economic divides in the United States, there are other factors like educational gaps and continued systematic discrimination amongst non-white Americans.

Our investigation hopes to examine and compare demographics in Chicago, Illinois, and college and post-secondary enrollment rates. We hope to associate certain demographic factors, their connections to college enrollment, and the trends they have influenced.

The higher a families wealth and status a person is born into, the better they are prepared to attend college and perpetuate their wealth. According to the Illinois State Board of education, “young adults who earn college credit are more likely to be employed and stay employed. Furthermore, an article from the US Department of Labor explained, in 2012, the employment rate for young adults was 87% for those with at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 75% for those who completed some college, and 64% for high school graduates” (illinoisreportcard.com).

As students ourselves, we realize our fortune to have the opportunity to attend post-secondary school in a nation where, while efforts to make education accessible are made, it is undoubtedly far more feasible for some than others.

Family income can be expected to be one of the primary drivers behind attending or not pursuing post-secondary education. Not only does it affect ones ability to pay for college itself, but it also might determine the high school one attends and its ability to prepare a student for college in terms of achievement and skills. This topic was covered well by This American Life, an NPR podcast, in their episode “The Problem We All Live With”, which is highly recommended by Max. Another episode of theirs called “The Campus Tour Has Been Cancelled” explores how Covid-19 has resulted in many American universities admitting a more significant proportion of students of colour, and lower income groups. As a result, they believe in relying on indicators other than SAT scores to admit students. The theory is that more financially well off students have access to better SAT preparation resources and therefore do better on the test.

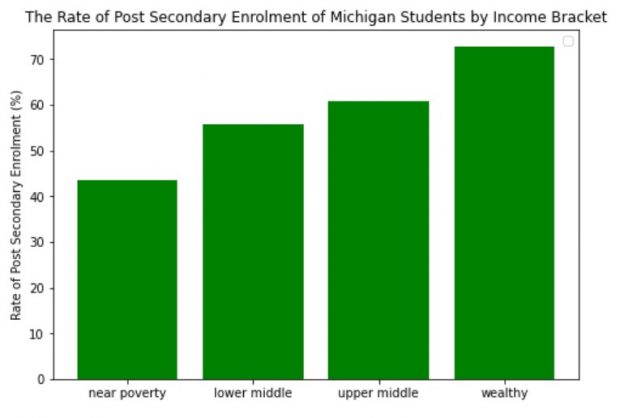

This theory seemed to show promise following the findings of a small project conducted by Max, where the percentage of high school graduates enrolling in college within one year compared to the ratio of median income to the national poverty level in Michigan. The findings were as follows.

As can be seen above, similar variables in the state of Michigan seem to show a reasonably clear trend favouring our hypothesis. The same variables were intended to be compared with minor differences such as college enrollment being reported by school rather than census tract and income being reported as median of tract rather than a series of counts of families falling in various classes. The above study was very simplistic. In this study, we set out to add more potential explanatory variables and represent the trend spatially.

In this study, Jake and Max attempt to quantify the relationship between various socio-economic characteristics of the city of Chicago and the rate at which high school graduates in a given census tract enrol in post-secondary school.