Analysis of my ‘Jammed’ Image

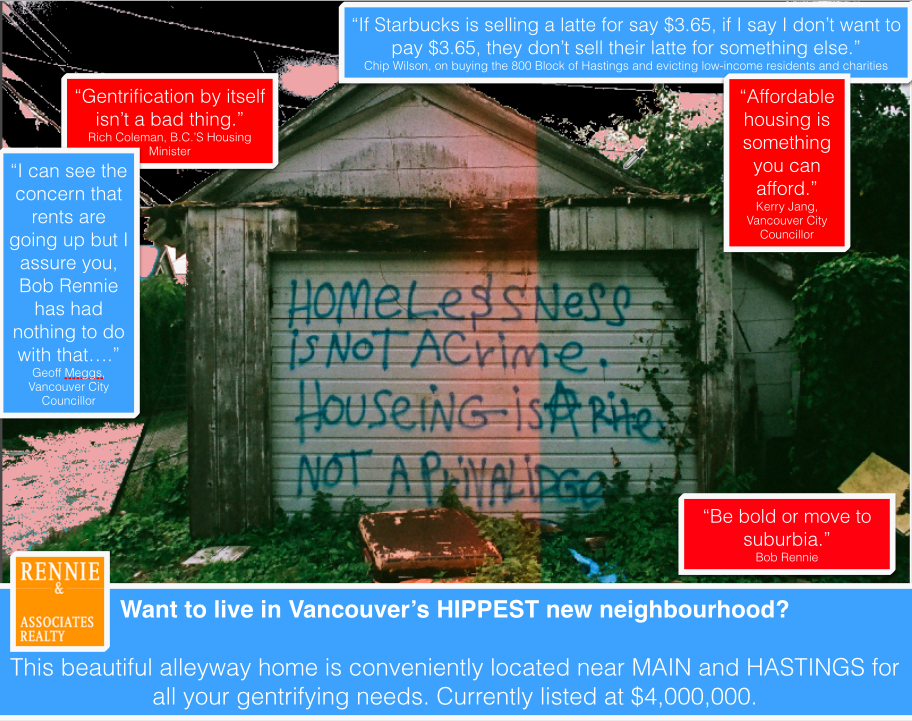

My jamming image is meant to illuminate the way in which Vancouver’s fetishization of property, reliance on neoliberalist ideals, and continued displacement and gentrification of communities, perpetuates inequality by reinforcing the notion that the city is a space solely for the super wealthy and elite.

In Vancouver, the far-reaching effects of the housing affordability crisis, and the rapid redevelopment of traditionally low-income neighbourhoods, has affected a large cross-section of the city’s population. In the DTES, where people are arguably most affected by the process of gentrification, stigma, the criminalization of residents and spaces, and other tactics have been used to justify and normalize the community’s changing landscape (Vancouver Sun, 2017).

The image I created is built around a photo I took in an alleyway in Strathcona. The message plastered across the dilapidated structure is clear- the need for affordable, social housing is growing rapidly.

Over top of this photograph I inserted a glossy banner, mocking the phrasing and sentiments reproduced in the original luxury condo ad. Surrounding the central image are quotes from politicians and local developers on the gentrification of the DTES. Their total lack of regard for the people and community they are working to push out showcases their .

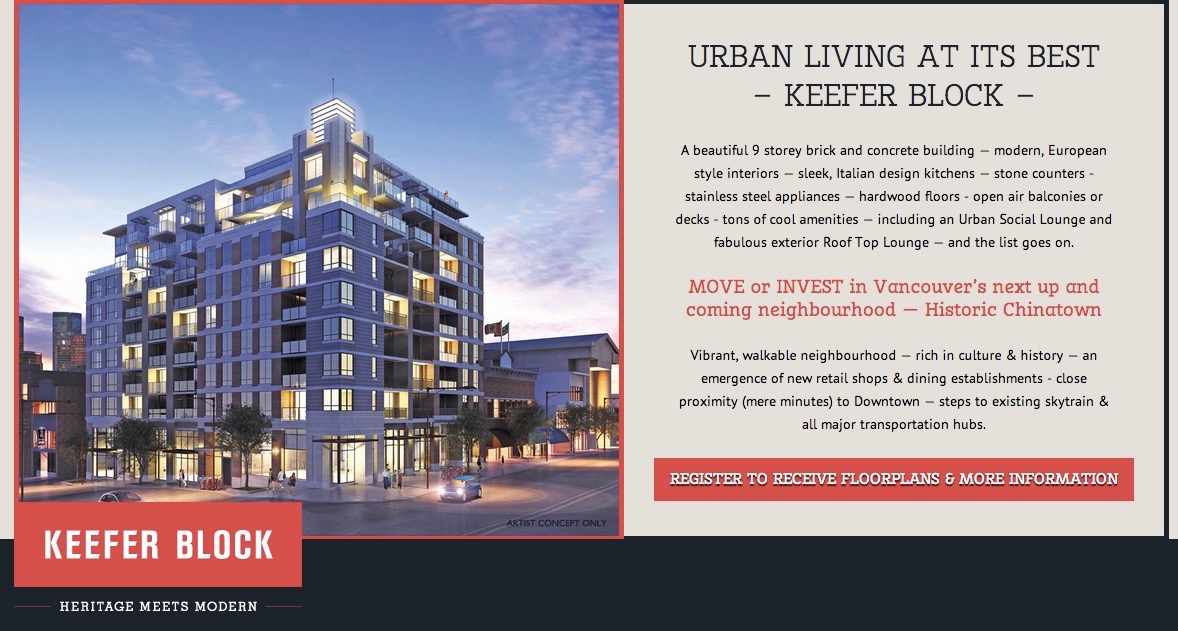

The juxtaposition of this jammed image, to the original ad, forces the viewer to confront the stark reality that condo developers and marketers often try to coverup. The creation of these new, and largely unattainable buildings, works to erase the area’s history, and displaces a large number of low-income residents that have been in the DTES for decades. Importantly, the removal of these individuals from their homes is not met with an equal push from the government to create affordable housing. All of these things together has helped to increase homelessness in Vancouver by 30% since last year, and maintain BC Housing’s 4,000 person long waitlist (CBC News, 2017).

The significant effects that a lack of adequate housing can have on low-income women living in the community, is demonstrated in Torchalla et. al’s (2015) qualitative analysis of the experiences of pregnant and postpartum women in the DTES. Here, the social determinants of health (housing being one of them) is shown to have a significant impact on women in the area. Without affordable and accessible housing, many struggle to maintain a quality of life.

Ultimately, my jammed image is meant to critically analyze the way in which condo developers and marketers work to erase the experiences of low-income folks living in the DTES, and displace entire communities for the benefit of the wealthy. This has significant social implications for the entire neighbourhood.

References

CBC News (2017). Homelessness up 30% in Metro Vancouver. Retrieved from: http://www.citationmachine.net/bibliographies/214213164?new=true

Torchalla, I., Aube Linden, I., Strehlau, V., Neilson, E. K., Krausz, M. (2015). “Like a lots happened with my whole childhood”: violence, trauma, and addiction in pregnant and postpartum women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Harm Reduction Journal, 12(1), 1-10.

Vancouver Sun (2017). Downtown Eastside Gentrification Creating ‘Zones of Exclusion’ for Community Residents. Retrieved from: http://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/downtown-eastside-gentrification-creating-zones-of-exclusion-for-residents-community-group