The early 1900s saw the demography of the northern United States of America drastically change. Emancipated African-Americans, filled with economic and cultural self-determination, had become increasingly frustrated with life in the South. The allure of civic participation, political equality, and an overall opportunity for a better life drove 1.6 million migrants to leave Southern states such as Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia between 1910 and 1930.

Up to, and during, the First World War, the influx of European labourers slowed to a halt, but the opportunities for unskilled labourers remained abundant. The Great Migration attracted hundreds of thousands of African-Americans to developing urban centers like New York City. The rapid introgression of African-Americans into northern states and cities left distinct fingerprints in the demography of these cities, especially at the neighbourhood scale. In New York, the neighbourhood of Harlem experienced the most notable change. What was once a predominantly white middle-class neighbourhood was now becoming an African-American community, primed by acquisition of real estate by African-American realtors and a church group.

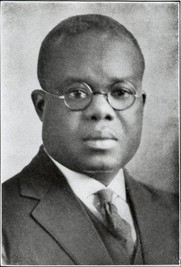

The early 1910s gave rise to the first stages of the Harlem Renaissance. An eruption of culture took the form of plays, poetry, photography, and paintings. The rejection of stereotypical and racist views throughout the work alluded to African-America’s absolute defiance in the face of international racism. For the first time, the reality of current African-American life described by African-Americans was being recognized by white America, and the world. In 1917, the first newspaper of the New Negro Movement was published. “The Voice” was a major source of political opinion and artistic work for the growing African-American middle class, and was an outlet for an educated class of black artists, intellectuals, and politicians. In addition, the newspaper’s creator, Hubert Harrison, founded the Liberty League, a political organization that held the arts in high regard.

While organizations such as Harrison’s helped define the “renaissance” at the time, they often criticized the notion of the term. It was a white term applied to a recently recognized, but deeply rooted, black culture. The prolificacy of African-Americans was only then being acknowledged by America as a powerful cultural force. However, perhaps the concentration of a previously disenfranchised group of people fuelled by the access to education, art, and economic opportunity, was enough to act as the localized budding of a global cultural change. This was a renaissance in the sense that it gave the concept of identity to a group of people who were denied that when it simultaneously existed firmly in the rest of the population. Perhaps it was strengthened by its cross disciplinary scope, which was honed by the works of writers, artists, actors, musicians, and thinkers, but it seems too narrow-minded to pinpoint any single cause, simply because it manifested itself as an international upwelling of black creativity.