Although she was a predominantly black neighbourhood in 1929, 81.5% of Harlem’s 10,319 businesses were owned by whites. Store fronts and sidewalks showed a stark contrast between the people who defined the neighbourhood, and those who subsisted economically from it. Many African-American run businesses took the form of beauty salons, and were operated in residential apartments above the streets.

Much of the business opportunity for African-American existed underground in gambling operations. In 1924, there were at least 30 major kingpins or “bankers” in the popular and lucrative numbers game. Tens of millions of dollars exchanged hands of clients, bankers, and collectors every year. Bankers employed bet collectors who in turn would take the bets made by clients. By the late 1920s, it is estimated that there were upwards of 1,000 collectors and 100,000 clients involved daily in playing the numbers. While the bankers profited greatly from the numerous transactions, many would donate generously to charity, and would give loans to aspiring businessman and needy residents. This evidence of what one might call altruism – exaggerated by the absence of the expected criminal mindset of such kingpins – seems to characterize a cohesion of the African-American community. Perhaps the novel sense of identity was mutually felt throughout the community, which brought it closer during its development, rather than allowing it to diverge. This is possibly a defining feature – even a catalyst – of a cultural renaissance, wherein uplift is felt and shared by all members of the culture.

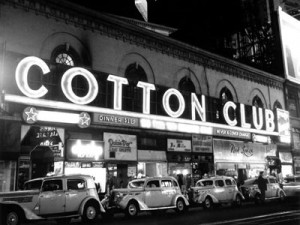

The nightclubs, cabarets, and speak-easies that drew much attention to Harlem were mainly owned and operated by whites. Harlemites benefitted very little from such enterprises, both financially and socially. Segregation of blacks from whites in areas of socially gathering was in part due to criminal involvement in the operation of these establishments. Chicago crime boss Owney Madden’s Cotton Club was one such place. Before 1922, Jack Johnson, a black heavy-weight world champ fighter, ran his business there, until he was forced to sell out. While the club featured many of the top black performers of the time, such as Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, and Duke Ellington, black patrons were not allowed in. This is a possible indication that past handicaps of African-Americans reappeared after the Great Migration. Perhaps the new adjustments made during the move did not do away with the deeply ingrained racial views in America and the world.

Households served as businesses for many tenants in addition to those who operated beauty salons. In response to the influx of whites to previously black clubs and lounges, many residents secretly opened up their homes as buffet flats during the evenings. There, bootlegged alcohol was served, and people danced to live music. Buffet flats served an important role during Prohibition, and also offered a place for prostitution and gambling to take place. Invitees often paid an entrance fee, which helped the tenant make rent and subsist. Buffet flats were, or course, located in residential areas of Harlem, far from clubs, police, and whites, a fact which may have allowed them to develop into an important component of African-American social life. These parties were very private, and were never advertised.

As poverty due to the economic downturn at the end of the 1920s reduced many areas of Harlem to slums, these rent parties became very important. To further help make rent, tenants began taking in lodgers, who often brought bad habits and crime along with them.