For this week’s post, I have chosen to respond to the following prompt:

Figuring out this place called home is a problem (87). Why? Why is it so problematic to figure out this place we call home: Canada? … Chamberlin says, “the sad fact is, the history of settlement around the world is the history of displacing other people from their lands, of discounting their livelihoods and destroying their languages” (78). Chamberlin goes on to “put this differently” (Para. 3). Explain that “different way” of looking at this, and discuss what you think of the differences and possible consequences of these “two ways” of understanding the history of settlement in Canada (Paterson, question 4).

I don’t remember learning to speak, but according to my family’s stories, my first word was “home.” I’ve always felt a strong connection the the ideas of place, family, and home. However, as my understanding of history, ancestry, and colonialism has grown, the complexity, confusion, and pain that I associate with this connection has also increased.

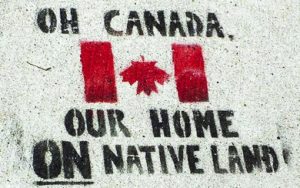

Stories can “give meaning and value to the places we call home” (Chamberlin 1), and the opening lines of Canada’s national anthem, a kind of story (Chamberlin 175), suggest that being at home here, in Canada, is simple if you’re considered to be a Canadian citizen. It’s “our home and native land” (O Canada). But what does this phrase actually mean? Whose “home” and “land” is being referred to as “ours?”

As suggested by author J. Edward Chamberlin, the history of settlement itself has been tied to displacing others, while also “discounting their livelihoods and destroying their languages” (78). This history features prominently in Canada’s story as Indigenous peoples, who have lived here for thousands of years, have been displaced and removed from their homelands, historically and currently. Not only that, but the cultures, livelihoods, and languages of peoples originally living here have been discounted and actively destroyed through initiatives such as reserves and residential schools, the last of which closed as recently as 1996 (CBC News).

This displacement and destruction is a central reason why calling Canada “home” is so complicated. For immigrants (including “settlers” whose families have been here for hundreds of years), it means trying to find home on land that, in most cases, has been illegally stolen and occupied, and is tied to a genocide of peoples and cultures. For people with Indigenous ancestry, as mentioned above, “home” has been largely affected too, as communities have been geographically divided, landscapes have been irreparably changed, and many of the stories and connections to place, language, and community have been denied.

However, Chamberlin also offers another perspective on this “history of settlement,” suggesting that, “[p]ut differently,” many of the world’s conflicts have been a story of “dismissing a different belief or different behaviour as unbelief or misbehaviour, and of discrediting those who believe or behave differently” (78). While this is closely related to his point mentioned above, it suggests that conflicts, such as those regarding “home,” have been tied to dismissing and creating the other, or “them and us” (Chamberlin 8). This dismissal and discreditation could be used to justify labelling one set of beliefs or behaviours as “right,” while indicating others are “wrong.”

For Canada, this included dismissing the beliefs and practices of people originally living here and actively trying to change this. In addition, stories and ideas such as terra nullius were created through this dismissal of different ways of using and perceiving land and place, and suggested that the usage of land by Indigenous peoples was leaving the land “vacant,” or not properly used, and helped to “justify” the occupation of lands by settlers.

So what does it mean to be at “home” on land that has such a conflicted story? This is a main reason why finding home in Canada can be so challenging–and problematic. Perhaps there really is “no place like home” (qtd. in Chamberlin 74) and this connection is found in the stories and concepts of home that we build for ourselves, which can “hold some people together and keep others apart” (Chamberlin 227). If stories do have this power, then perhaps they can also help us to recognize the past, and create a new story, and “home,” for all of us.

—

Works Cited Continue reading