For my post this week, I will be reflecting on pages 99-109 in Green Grass, Running Water and finding some of the references and underlying stories contained within the stories explicitly shared in this text.

While reading Green Grass, Running Water (by Thomas King), I was struck by the number of plays on names and words, allusions, and subtle references that King made throughout the novel. However, after reflecting on story and reading posts by my classmates, as well as Jane Flick’s reading notes, I found there were even more layers of meaning and depth to the story than I initially realized. In particular, cycles throughout the story that connected to Florida and ledger art sparked my curiosity and was one of the main reasons I chose to focus on this section of the novel. While there were many references throughout the novel, this post and reflection focuses on some of the references found within a small section of the book, with the intention of revealing some of the layers of story woven into King’s writing.

Sitting around, drawing pictures in Florida (King, Green Grass, Running Water 99)

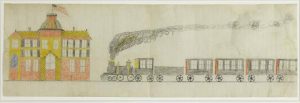

The pages I chose begin with First Woman and Ahdamn being taken by soldiers to a train station where they board a train for Florida. This section alludes to the transportation and imprisonment of 72 Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, and Arapaho from their traditional lands to Fort Sill and, later, to Fort Marion, where they were imprisoned from 1875 to 1878 (King, Green Grass, Running Water 18; “Red River War”). It was claimed that the prisoners were all leaders and combatants in the Red River War, although it has also been suggested that, for many of them, “their primary crime was that they were Indians who had led a traditional Plains Indian life,” especially as they did not have a trial before being imprisoned (Ojibwa).

In addition to these connections, Coyote suggests going to Miami and Fort Lauderdale, which could be a reference to the history of these places, as Miami was named after an Indigenous word and is built on an Indigenous village site while Fort Lauderdale was also built on land traditionally used by Indigenous nations (Tequesta) and was later used in the Second Seminole War (“Fort Lauderdale History”). In a less connected sense, Coyote’s suggestion could also simply be based on a desire to visit the beaches in Miami and Fort Lauderdale. Still, the story, along with First Woman and Ahdamn, proceed to Fort Marion, rather than listening to Coyote’s suggestions.

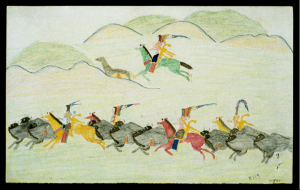

Once at Fort Marion, the prisoners were “converted” to Christianity (many did not keep this as a religion) and educated in English ways, with assimilation being the end goal; one of the techniques for this assimilation and “civilizing” was “encouraging” the prisoners to draw (Adams; Coffee; Keeping History). Ahdamn’s drawing, and his resulting “fame” that takes place at Fort Marion, alludes to this ledger art that was produced by those held captive at Fort Marion. This art was created by some of the prisoners during their time at Fort Marion and often was sold to visitors — the artwork is still bought and sold today (Adams). Accordingly, some of these pieces of art depicted cultural life, including the Sun Dance (“Keeping History”), another important part of the story for King’s characters.

Connecting cycles and directions

The Sun Dance is one of the connections that many of the characters in King’s novel share, regardless of the year the dance occurs as, like many of King’s themes, it too is cyclic and has the potential to connect the characters across time and space. However, throughout the book, broader connections to the theme of interconnection and cycles can be found. The section I chose transitions from one section to another and, as author Jane Flick suggests, these different sections indicate different directions and colours which relate to both the Medicine Lodge, a part of the Sun Dance for many nations (Stover), and the alternative names (Mr. Red, Mr. Blue, Mr. Green, and Mr. Black) that First Woman, Changing Woman, Thought Woman, and Old Woman go by in Dr. Hovaugh’s records (Flick 143; King, Green Grass, Running Water 53).

This transition also marks the beginning of another creation story, a story of Changing Woman. This transition gives a turn to another one of the four Indian comrades (unlike in much of Western society, different creation stories each have a turn) and presents a reference to water and, in this way, new beginnings overall as both Lionel is in a puddle of water and, perhaps less significantly, the toilet floods at the Dead Dog Cafe (King, Green Grass, Running Water 106-107). Changing Woman’s name also suggests a different phase of life (changing from a child to an adult) following First Woman, and, in this way, connects to larger cycles of life.

Finding significance in names

Similar to how significance can be found in the names of First Woman and Changing Woman in reference to life stages, numerous other references can be found within the names of King’s characters. Even within these few pages, character and location names hint at deeper meanings to their stories. For instance, First Woman’s name also alludes to other creation stories that include a first woman. In the case of Green Grass, Running Water, First Woman also alludes to Christian stories of Eve and Adam as First Woman meets and Ahdamn and they live in a garden for a time (King, Green Grass, Running Water 40). In addition to this, the alternatives names for First Woman and Ahdamn, Lone Ranger and Tonto, also reference another story that has had impacts on perceptions of Indigenous peoples in North America, and could be a connection to some of King’s photography experiences (Flick 141). While these names are not hugely emphasized in this section of the book, they are still reoccurring references (in addition to Robinson Crusoe, Hawkeye, and Ishmael), which could also be perceived as references to how stories and stereotypes can remain with a person, regardless of the context.

Beyond these character names, the name of Latisha’s restaurant, the Dead Dog Cafe, seems to indirectly reference the beginning of the novel where Coyote’s dream starts to get out of hand and ends-up wanting to be a dog. However, the dog end-up as a GOD instead as “when that Coyote Dream thinks about being a dog, it gets everything mixed-up. It gets everything backward” (King, Green Grass, Running Water 2). In addition, after the publication of Green Grass, Running Water, King also wrote and co-hosted a radio show, the Dead Dog Cafe Comedy Hour, which also takes place within the (fictional) town of Blossom, Alberta, and provokes similar questions and reflections (such as those about stereotypes, “Indians,” and stories) to Green Grass, Running Water.

Overall, this only skimmed the surface of the many connections that one can find within King’s writing; it is incredible to reflect on the many layers of understanding and meaning that can be found within his work.

—

Works Cited Continue reading