For this post, I will be responding to the following prompt:

[R]efer to Sparke’s article, “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation” … [and] write a blog that explains Sparke’s analysis of what Judge McEachern might have meant by this statement: “We’ll call this the map that roared.” (Paterson, question 3)

I have always found maps to be fascinating. They spark my imagination by hinting about places that I may or may not know and can relay large amounts of information about the thing (typically a place) they are depicting, as well as potentially revealing some of the underlying perspectives behind the map’s making. However, along these lines, maps, while often portrayed as unbiased and objective, can be hugely political and powerful depending on what the cartographer(s) choose to, or to not, show.

As quoted by Matthew Sparke in his article “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation,” in the 1987 court case regarding Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en sovereignty and land rights (463) the court judge, Allan McEachern, accordingly called the map that the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en brought with them “the map that roared” (Sparke 468). This statement could be interpreted in a number of different ways and Sparke’s analysis provides a couple of potential ways that this statement could be viewed.

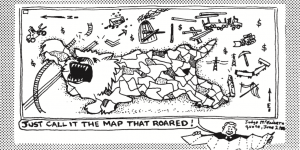

“A Map that Roared” by Don Monet

The first analysis that Sparke provides indicates that these comments, made by McEachern, could be interpreted as suggesting that the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en plaintiffs and their map are “ramshackled” and “anachronistic” in a scornful, or “derisory,” way (468). More specifically, Sparke indicates that the comment could be suggesting that the map is a “paper tiger” and/or could be referring to a 1959 movie called “The Mouse that Roared” (468), in which a small territory declares war on the United States in order to replenish the territory’s treasury (Erickson).

However, Sparke and others, such as Don Monet through his artwork above, also provide an alternative analysis to this statement, as the concept of a roaring map also evokes ideas of resistance (Sparke 468) and potentially new stories being told loudly and clearly. To expand, by its “roaring refusal of the orientation systems, the trap lines, the property lines, the electricity lines, the pipelines, the logging roads, the clear-cuts, and all the other accoutrements of Canadian colonialism on native land” (Sparke 468), this map challenged assumptions of map objectivity and plotted another story of the land, one that had gone mostly unrecognized by mainstream colonial maps. In this way, the maps that the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en worked to create and brought to the courtroom, not only challenged the Canadian legal “game” (Sparke 471), but, like Thomas King’s contrast of creation stories, showed that another “story” could be used to narrate a place that had had another story imposed on it.

In fact, maps have contributed to colonialism since first contact through perpetuating myths such as terra nullius and detaching people, stories, and living connections from a place by “abstracting” the space to something that was empty (Harris 175; Sparke 474). In the words of geographer Cole Harris, maps, such as early colonial ones, “erased almost all the contents of the space they depicted” (175). This apparent emptiness made it easy for lands to be plotted and claimed by others, even while those who were doing this could be on another continent.

However, maps tell stories (Fotiadis 6) and mapping is now also being used to offer alternative perspectives, stories, and understandings of place, and different kinds of maps, such as story and oral maps, are also contributing to these re-imagined mappings. For example, while some may argue that the maps created by the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en for the 1987 court case did not result in the plaintiff’s desired objective, these maps still helped to articulate their “claim to their territories in a way the judge might understand” (Sparke 472) and provided a powerful alternative to the barren seeming colonial maps, presenting “a landscape rich with the historical geographies of Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan names and meanings” (Sparke 474). Another example of this re-imaging of maps is the Mapping Indigenous LA project which is using storymaps to “uncover and highlight the multiple layers of indigenous Los Angeles” while making “the rich Indigenous identities and histories that are often hidden … yet deeply embedded in the history of Los Angeles” more visible (“About Our Project”). Among other things, these maps are helping to re-story the landscape and bring forward the layers and presences on the land that often remain hidden in Western cartography.

Finally, in addition to the points mentioned above, maps have contributed to various narratives through the process of naming. In this sense, I found it quite interesting to notice that, according to Sparke, the first thing that judge McEachern did when first unfolding one of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en territory maps was to name it, or say what they would call it by stating: “we’ll call it the map that roared” (468). Perhaps this act in and of itself suggests the power of this map as, while the judge’s comment could be considered derisory, it could also be seen as the judge’s attempt to claim and to regain some control over something that seemed to be “roaring” with another powerful perspective.

—

Works Cited* Continue reading