3:3— Hypertexting Green Grass Running Water

For this week’s blog post, my task is to explore the allusions, names, and subtext of pages 60 – 69 in Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water. I’ll begin with a quick summary of the plot during this segment of the novel to orient my discussion of the text’s details below.

From pages 60 – 64, we hear about the aftermath of Lionel’s arrest in Green River, Wyoming, for being associated with members of the American Indian Movement, including a first jail stint for disturbing the peace, his return to the hotel in Salt Lake City, a second jail stint for leaving the hotel without paying the bill, and his inglorious return to Blossom, unemployed and with a criminal record. Next, from pages 65 – 67, we hear about Alberta’s failed attempt to execute option three on her list of ways to get pregnant, namely pick up a handsome stranger at a bar. Lastly, on pages 68 and 69, we return to the story of First Woman as it is told to Coyote, just as First Woman decides to leave the garden after GOD jumps in and starts making a brouhaha.

The notes below are organized in order of their appearance in the text.

Duncan Scott

This is Lionel’s boss at the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs (D.I.A.). We now call this the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development. But Duncan Scott was a real head of the D.I.A. from 1913 – 1932, where he was an adamant supporter of educating First Nations children (he made elementary education compulsory for these children) and strongly supported the religious residential school model. First Nations children were often left in the lurch by this system after elementary school, unable to continue to higher education due to limited availability but also dislocated from their family and ancestral traditions. The residential school system was fraught with problems as well as outright abuse. Scott is also known as a Confederation Poet, a distinction given to four male poets of that era. His appearance as Lionel’s boss and subsequent abandonment of Lionel after he gets into trouble down south highlight the historical lack of genuine care for and understanding of First Nations people by the Department of Indian Affairs.

Tom and Gerry, Salt Lake City hotel employees

Tom and Jerry is a popular Warner Brothers children’s cartoon involving Tom the cat chasing Jerry the mouse. It was first established in the 1940s and has generated controversy over its depiction of African-American people, including portraying characters in blackface and as “black mammy” stereotypes. The multiple references to blond white men in the hotel staff suggest racist overtones, lending support to this connection.

Chip and Dale, Salt Lake City police officers

The combined names of this pair could be a subtle reference to the Las Vegas Chippendales, a popular male erotic dance company founded in 1979. The company performs across North America and worldwide. King just finished describing the hotel employees as young, blond, and attractive men, so this is a somewhat plausible connection. Chippendale is also a brand of furniture, but that connection didn’t seem to fit here.

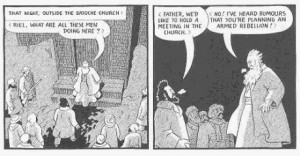

George Armstrong Custer and the Battle of Little Bighorn

General Custer in the Battle of Little Bighorn, as imagined by an artist of his time (BBC Bitesize).

Lionel looks closely at a painting depicting this battle in the hotel lobby, where Custer, a somewhat incompetent American military officer, and all his men were outnumbered and killed by Native American warriors in the Battle of Little Bighorn. Their deaths were used in government propaganda to rally white Americans against the warriors and led to an increase in armed conflict with Native Americans (the Indian Wars), as well as increased assimilation efforts by the American government (BBC Bitesize).

The Shagganappi

This is the name of the Calgary lounge Alberta scopes out for attracting a potential anonymous father for her child. She doesn’t end up going inside, though. The Shagganappi is also a book of short stories by E. Pauline Johnson, a woman of English-Mohawk ancestry who performed her poetry in front of white North American and European audiences during the late 1800s. She actually had two costumes, a First Nations mishmash for the first half of her performances and an English one for the second half (Landau). At one point in her career, she recited her poetry at the same event as Duncan Scott. She died in her 50s from breast cancer and is buried in Stanley Park (Mobbs).

Emily Pauline Johnson (1861 – 1913), an English-Mohawk Canadian poet and performance artist. We meet her in GGRW at the Dead Dog Cafe and also are reminded of her publications when Alberta heads for the Shagganappi lounge, The Shagganappi being the title of one of Johnson’s short story collections. Image from Landau.

Works Cited:

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162 1999: 140 – 172. Web. 22 February 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development homepage. Government of Canada, 6 March 2014. 16 March 2014.

belkiss2. “Tom and Jerry Mammy Two Shoes …” Youtube. 16 March 2014.

Chippendales homepage. Chippendales 2012. Web. 16 March 2014.

“The Battle of the Little Bighorn 1876 and the end of Native American way of life.” BBC Bitesize, BBC, 2014. 16 March 2014.

Landau, Emily. “Double Vision.” Walrus July/August 2012. Web. 16 March 2014.

Johnson, E. Pauline. The Shagganappi. Project Gutenberg, 2004. Web. 16 March 2014.

Mobbs, Leslie. “E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), 1861 – 1913.” AuthentiCity, 7 March 2013. Web. 16 March 2014.