Canada is often described as a multicultural nation, by which we mean that the unique colours of many cultures are preserved in a carefully stitched quilt of peaceful communities.

But to put it another way, in the words of Northrop Frye, we are a nation with a “garrison mentality” (Frye 227). At times, we have bracketed ourselves in exclusive, strictly ordered societies in order to protect ourselves from mysterious and terrifying external forces. These forces may once have been connected to the extremes of Canada’s natural environment, but historically as well as presently, we also fear the economic, moral, or creative powers of others who are somehow different from us. In the present day, we might consider the garrison mentality working at the level of the individual more than the community: where do we each draw lines between the acceptable and familiar and the chaotic and upsetting in our own minds? Do we garrison ourselves from certain experiences, thoughts, or emotions?

The story of Manitoba’s Louis Riel is one example of a battle between garrisons, both literal and figurative. Both the inability of certain groups to see past the fears and assumptions made about others and the huge economic disparity between the interested parties in the conflict fueled the process of rebellion.

In the 1850s, the area forming present-day Ontario, Quebec, and Manitoba contained a mixture of societies, each distinct in culture, language, religion, and economic power. Ontario generally had a Protestant, English-speaking society with relatively expansive economic privilege, Quebec’s residents spoke French, practiced Catholicism and had moderate economic privilege, while Manitoba exhibited a more diverse culture with an accompanying range of economic privileges (Brown, Stanley np). Manitoba at this time was not a province but simply a parcel of land owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which was then interested in exploiting the land’s resources (furs and timber) (Dunn Rupert np). The profits from these activities fell primarily into the hands of English Protestant executives, who, while ensuring that rules were obeyed by stationing plenty of company representatives and law enforcement personnel in the forts and settlements of the regions, did not live in Manitoba or recognize its unique, diverse culture. This special culture was born from the intersection of First Nations and French-Canadian societies in fur-trapping communities along Manitoba’s waterways (Dunn Metis np). These people, the Metis, spoke French and maybe a First Nations language or two, besides being Catholics with strong ties to Quebec (Dunn Metis np). They also farmed HBC lands and trapped furs, which were intended to be sold exclusively to the HBC under a legally enforced monopoly (Dunn Rupert np). There are stories of some flexibility in this legislation, however, as described in a family story told by Louis Riel’s great-grand niece. As the century progressed, more and more English settlers moved to Manitoba to farm on the riverfront, at times displacing Metis farmers who had to resettle on less desirable land (Flanagan 30 – 31). Simultaneously, the HBC gradually withdrew from the fur-trading side of business and moved on to dealing with the division and sale of its lands (Flanagan 30). A trans-continental railway was also in the works to connect the region to the more eastern Canada (Marsh np). Change was afoot in the Red River settlements, and many people wished to speak their mind about what was happening to their homes and livelihoods (Flanagan 30 – 31).

Enter the Metis leader Louis Riel. Born in Manitoba, educated in Montreal, visitor and eventual citizen of the US, poet, and devout Catholic, he offered several solutions to the government of Canada that addressed the concerns of his people, who felt their needs were unrepresented by the far-away federal government (Flanagan 34). Some successful solutions included the incorporation of Manitoba as an official province along with getting Manitoban representation in Canada’s Parliament (if only two seats), as well as the creation of a carefully structured, hybrid provisional government for the region (Flanagan 39, 34). The hybrid nature of the government mandated equal numbers of English- and French-speaking Manitobans. Less successful in the long term were Riel’s detention of certain riotous English settlers, culminating in the trial and execution of one particularly obnoxious individual, Thomas Scott, after he was involved in the assault of a Metis man (Flanagan 33). This forced Riel to leave Canada and give up his elected Parliament position due to Canadian charges he faced (Flanagan 35). But overall, Riel’s approach to governance for Manitoba was positively received by the Metis and even by many of the English settlers.

Sir John A. Macdonald had other ideas for Manitoba, however. Anxious to avoid “another Quebec,” a society garrisoned by language, religion and culture from English Canada and therefore difficult to persuade during election season, Macdonald wanted to empower the English half of Manitoban society at the expense of the Metis (Brown 136). In response to English Canadian protests in Ontario over the death of Thomas Scott, he even denied the Metis various requests for resurveying of lands and money, actions he knew would incite armed rebellion in the region (Brown 136). And since Manitoba was by then officially a part of Canada, he was not worried that the Metis would go to the Americans for military assistance (Brown 136). Finally, he wanted to exercise Canada’s new railway muscles. Without the need to send soldiers west immediately, investors, taxpayers, and Parliament were not willing to spend the huge sum required to complete the transcontinental line (Marsh np). For Macdonald, the Northwest Rebellion was perfectly timed to drive completion of his pet railway project as well as pacify Ontarian voters. The message of Riel and his provisional government on the subject of self-determination as Metis people, ability to control their lands from a shorter distance than Ottawa, and willingness to participate in the democratic process were ignored as their small-scale armed rebellion was quickly crushed by Canadian soldiers (Beal np).

Given this historical background, we can now discuss the role of the Metis as a founding partner in Canadian culture. Their status as people of mixed indigenous and French-Canadian background was quite unique in Canada at the time and perhaps contributed to Riel’s ability to unite the English and Metis people of the Red River valley into one government. However, English Canadians living east of Manitoba were not interested in such cultural quilting projects. Their privilege extended deep into Canadian government and economic power, as they were given priority access to land resources as well as controlling the majority of Parliament (Stanley np). They were not interested in a dilution of their power. The First Nations people in Ontario and to a lesser extent Manitoba had already been stripped of their lands and much of their negotiating power, and the English Canadian population, under the leadership of Macdonald as well as Alexander Mackenzie, saw the economic vulnerability of the Metis population at the time of the rebellion as a chance to reduce their power closer to the level of First Nations people. In this they were successful, quashing the rebellion and imposing the will of Parliament on the Metis while stripping them of their leader, Riel (Beal np). But not only was a stranglehold on economic power important to English Canadians. Culturally and morally, they firmly believed themselves to be in the superior position, and this was further impetus to assert their domination over the “half-breeds” of Manitoba (Brown 135). Coleman also describes this as a domination of the supposedly superior “White spirit,” that highlighted economic gains and entrepreneurial success as the ultimate goals of civilized society (Coleman 12). Perhaps even Riel’s personal cultural quilt, one including patches of strong, mystic Catholic faith, gifts for leadership and reconciliation, poetry, and the ability to traverse multiple languages, threatened English Canadian expectations of “a British model of civility,” characterized by much less diversity and much more conformity to established cultural templates (Coleman 5). We see this quilt personified by the appearance of Louie, Ray, and Al as separate individuals in Green Grass, Running Water (King 334).

The episode of Louis Riel shows an incredible contrast between a genuine effort to reconcile and empower multiple stakeholders in the Red River valley, through Riel’s creation of a bi-representational government (note that we still do not see the First Nations people involved) and the monopolizing English Canadian effort to destroy it. Riel’s side of the situation has only been publicly recognized and made a part of official history since Canada’s centennial celebrations, when various efforts including the creation of a Louis Riel opera offered his perspective on Manitoba’s history. The stitching of Riel’s story into Canadian history offers a contrasting Canadian ideology beyond the factual implications of his life and accomplishments.

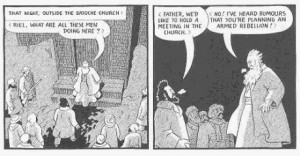

Aside: One highly entertaining story of Riel’s life is presented in Chester Brown’s Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography. It’s a great intro to some of the history surrounding Riel’s life as well as the major political factors at play in Canada during his time.

Excerpt from Chester Brown’s graphic biography of Louis Riel: the eve of the North-West Rebellion (Brown).

Works Cited

Beal, Bob, and Rod Macleod. “North-West Rebellion.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, 02 February 2006. Web. 14 April 2014.

Brown, Chester. Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2003. Print.

Coleman, Daniel. White Civility: The Literary Project of English Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006. Print.

Dunn, William, and Linda West. “The Metis.” Canada: A Country by Consent. Ottawa: Artistic Productions Limited, 2011. Web. 14 April 2014.

Dunn, William, and Linda West. “Rupert’s Land.” Canada: A Country by Consent. Ottawa: Artistic Productions Limited, 2011. Web. 14 April 2014.

Flanagan, Thomas. Louis ‘David’ Riel: ‘Prophet of the New World’, Revised Edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996. Web. UBC Library. 14 April 2014.

Frye, Northrop. The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination. Toronto: Anansi, 2011. Print.

kavpro. “Quilt of Belonging.” Youtube. Youtube, August 2009. 1 March 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Marsh, James. “Railway History.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, 25 March 2009. Web. 14 April 2014.

Stanley, George F.G. “Louis Riel.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, 04 April 2013. Web. 14 April 2014.

Teillet, Jean. “Bragging Rights.” The Walrus. The Walrus Foundation, November 2010. Web. 1 March 2014.

Turgeon, Bernard. “Bernard Turgeon – Louis Riel.” Youtube. Youtube, January 2013. 1 March 2014.

🙂

Hi Keely,

I really enjoy reading the contents in your blogs and engaging in dialogue with you, I was wondering if you have formed a group for the conference yet? Is there space for an extra person? Would you like to start a group with me? Is there anyone else in the class you’d like to work with or is there anyone else reading this who would also be interested in joining a group?

Just throwing it out there… let me know!

Vivian

Vivian

I’m really sorry, Vivian, but I’m already part of a group with Chris, Zara and Cristabel. I hope you’re able to find more group members okay! Let me know if not, maybe we could work in groups larger than 4.

Keely